In Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police and Punish the Poor, Virginia Eubanks outlines the life-and-death impacts of automated decision-making on public services in the USA through three case studies relating to welfare provision, homelessness and child protection services. Centralising the stories and experiences of her subjects with sensitivity while also drawing on statistical data, Eubanks offers a valuable and compelling contribution to discussions of inequality and poverty today, writes Louise Russell-Prywata.

Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police and Punish the Poor. Virginia Eubanks. St Martin’s Press. 2018.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

From an algorithm scoring newborn babies on their future risk of being abused to one million denials of welfare benefits in Indiana, Automating Inequality is a deeply unsettling exploration of the impact of automated decision-making on public services in America. It manages to disturb without sensationalising, and avoids (for the most part) preaching ideology. It does so by centring the stories of individuals who have experienced the negative consequences of automated decision-making.

Political scientist and technologist Virginia Eubanks argues compellingly that automated decision-making in social welfare provision is just the latest in a long history of measures that profile, police and punish poor people in the USA. Using three case studies, Eubanks builds an argument that automated decision-making is much further reaching and likely to have worse repercussions than previous non-digital mechanisms, such as nineteenth-century poorhouses.

Having set out this thesis in her opening chapter, the following three chapters each present a case study: welfare decision-making technology in Indiana; an automated system to match LA’s homeless to available housing; and an algorithm to target preventative child protection interventions in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

The story of Indiana’s welfare reform contains all the key elements of an automation bogeyman: an explicit aim to reduce costs and move people off benefits; a whiff of dodginess about the award process for a $1.3 billion contract to privatise a state service; widespread tech failure upon implementation; the inability to effectively hold the corporate contractor to account for this failure; the removal of human connections; and pressure on community services such as food banks to deal with the consequences.

But, as Eubanks aptly shows, its worst feature is the life and death impacts on the poorest and most vulnerable residents of Indiana. Eubanks presents people’s stories through the voices of those who experienced it as well as the staff who worked through the changing system. Throughout this, and across the entire book, Eubanks takes incredible care to respectfully and accurately present people’s experiences, and this gives the text a disarming, almost understated honesty.

Image Credit: (CreativeMerlin CCO)

For instance, Eubanks narrates how six-year-old Sophie Stipes, ‘a lively, sunny, stubborn girl with dark brown hair, wide chocolate eyes’ (40), received a letter saying that her Medicaid benefits – which kept her alive – would be stopped in less than a month, as she had ‘failed to cooperate’. This was how the automated system dealt with a minor paperwork error made by her parents, who Eubanks paints a rounded picture of as being dedicated and resilient. Helped by these traits, and some social capital, they managed to get Sophie’s Medicaid reinstated in time. Eubanks points out that, in all likelihood, others were not as lucky; as she quotes Sophie’s father:

My wife is persistent, intelligent – I mean, it should have been a breeze for her to get the paperwork turned in correctly. I just can’t imagine people with lesser skills [. . .] I know they couldn’t, they didn’t do it (77).

For readers in the UK, it is worth highlighting that public welfare in the USA such as Medicaid applies to a much smaller percentage of people than equivalent benefits in the UK, and is generally only accessible to the most seriously disadvantaged residents. The failure of automated systems to support the poorest and most vulnerable people in the richest country in the world is a theme that Eubanks highlights throughout the book.

Eubanks’s story-led approach allows her to paint detailed pictures of what it is like for people affected by automated decision-making – from the exasperation felt by a process that expects people to apply online when many don’t have internet access, to the dilemma faced by someone of little resources deciding whether to challenge a system when they know they are in the right, but in the knowledge that if that system denies them justice, it will be at huge human cost. And it is not just other people’s stories that Eubanks presents: the book opens with her own family’s highly personal encounter with the sudden withdrawal of health insurance due to an error made in an automated assessment system.

Eubanks visited the locations of all three case studies extensively whilst researching Automating Inequality, and personal observations and anecdotes are scattered throughout the book. The effect is to make the book both readable and authentic. For example, in the chapter on the automatic homeless-to-housing matching tool in LA, she writes about seeing a homeless man sleeping outside the dog parlour; a person and their dog step past them into the dog parlour; she observes that the dog has shoes yet the sleeping man does not. These observations are presented frankly but without explicit ideological reaction or outrage; these are left to the reader to feel, and this is very effective. However, as someone who has spent their career working for social justice, I am predisposed to feeling this outrage; I wonder if readers with a different socio-political lens might have benefited from additional context to drive home the fact that the problem with automated decision-making systems is not primarily an issue affecting a few tragic cases.

Eubanks does take steps to provide this context, and this review should not give the impression that Automating Inequality is light on statistics and secondary research. Eubanks pans out to discuss the huge rise in error rates made by the new automated welfare system in Indiana, and the steep increase in the number of denied applications, which doubled to over one million in three years. A sense of scale is given through inclusion of the number of people affected and the financial costs, and there is rich discussion throughout the book of the historical context of each case. When discussing Allegheny County’s predictive algorithm for child neglect and abuse, she gives an overview of its statistical features and the use of proxy variables to explain how the algorithm is flawed, as it predicts the decisions of the community rather than which children get harmed. Sliding in some basic statistical concepts without the reader needing to panic is definitely to be commended!

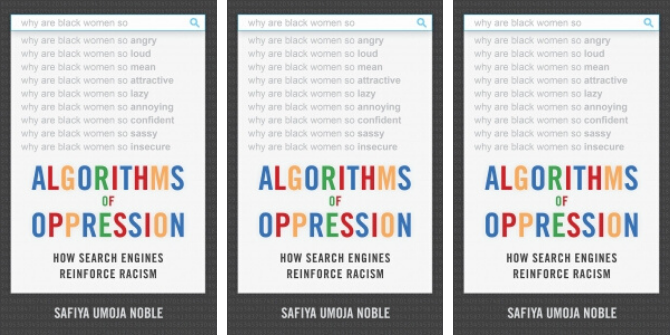

Intersections of race and class are woven throughout the book. Eubanks notes the disproportionate impact of Indiana’s welfare reforms on people of colour, whilst – perhaps pragmatically for a broad US readership – still underlining that white working-class people suffered. She mentions the gendered implications of welfare reforms, although this line of discussion could have been extended – for example, while all the senators and decision-makers in the Indiana case are male and almost all of the people whose stories are discussed are female, this wider gender imbalance is not noted.

At its heart, this is a book about poverty and how American society views the poor. The verdict is damning: poor people are seen as lesser people, sometimes barely as people at all. Eubanks illustrates incisively how these views are being embedded in an increasing number and variety of new tech tools, drawing them together to conceptualise a ‘digital poorhouse’ of the twenty-first century. The digital poorhouse, she argues, can act more quickly, at greater scale and with actions that can be hidden by greater complexity than the physical poorhouses that policed, profiled and punished previous generations. Nonetheless, she argues, we are still fighting the same civil rights problem of racialised and class-based inequalities.

It is logical, therefore, that in her final chapter on solutions, Eubanks argues for the need to focus on social movements to build empathy and change people’s views of the poor, and helpfully draws on the successes of the US civil rights movement. Although there is limited discussion of the difference between forging group identity as African American versus ‘poor American’, and she only briefly mentions huge policy solutions such as jobs and basic income, this is understandable given the core purpose of the book: to expose ‘how high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor’. Automating Inequality certainly achieves this for an increasingly important equality issue, promoting emotive shifts more often than concrete actions, but making a valuable and compelling contribution to the expanding body of writing in this area.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

12 Comments