In Accounting for Capitalism: The World the Clerk Made, Michael Zakim examines how an emergent class of finance professionals fundamentally transformed the foundations of the US economy and democracy in the nineteenth century. This thorough and cogently argued investigation demonstrates the grand historical consequences wrought by these lesser-known enablers of a new economic system, finds Jeff Roquen.

Accounting for Capitalism: The World the Clerk Made. Michael Zakim. University of Chicago Press. 2018.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Unlike his father, he possessed an uncommon amount of wit, optimism and ambition. After joining a crew to guide a boat down the Mississippi River to trade its onboard shipment at the Port of New Orleans, a young Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) returned to the state of Illinois and relocated to the town of New Salem to work at a small store. His decision to leave the family farm and embrace the rising tide of entrepreneurship in 1831 reflected the temper of the times and an ongoing, national recalibration of the American spirit.

In Accounting for Capitalism: The World the Clerk Made, Michael Zakim, a professor of history at Tel Aviv University, carefully examines how a new class of finance professionals within the emerging industrial order of the nineteenth century fundamentally transformed the ideological underpinnings of the American economy and democracy. From his rigorous and insightful investigation, the rise of the bookkeeper as a progenitor of modern capitalism may also be credited with refounding the nation on the basis of mobility and opportunism.

From the opening pages in the Introduction through to Chapter One, ‘Paperwork’, Zakim portrays a still nascent republic in constant flux. Upon the completion of the Erie Canal from the Hudson River to Lake Erie near Buffalo and Niagara Falls in 1825, the cost and time to transport goods from New York City and its port to the ‘West’ dramatically decreased. Consequently, the subsequent construction of a network of roads, turnpikes, additional canals and railroad lines created sizable immigrant flows into Illinois, Ohio and the territories of Michigan and Wisconsin. To manage the voluminous trade of commodities, an expansive commercial infrastructure – which included ‘counting rooms, credit agencies, import houses, commission businesses […] wholesale warehouses’ and retail centres – materialised alongside a demand for desk-bound specialists dedicated to accurately inventorying, processing and calculating the profit and loss of all transactions to the exact penny (17). Over several decades, standardised accounting practices not only evolved into the universal language of business, but also formed the basis of the new money-centred world. In recording credits and debits and posting balances, the market became both tangible and, ultimately, manageable (46).

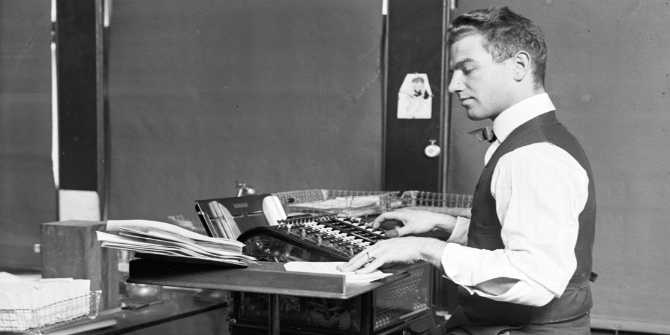

Image Credit: Crop of image of ‘Engineering Department clerical worker at adding machine, 1915’ by Seattle Municipal Archives is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Image Credit: Crop of image of ‘Engineering Department clerical worker at adding machine, 1915’ by Seattle Municipal Archives is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The second chapter, which surveys ‘Market Society’ from a socioeconomic perspective, synthesises at least two generations of scholarship and largely captures the seismic rupture of the market revolution. Half a century after the Declaration of Independence (1776), agriculture still dominated America. In the advent of economies of scale and large brick-and-mortar enterprises, businesses began recruiting clerks in droves. Hence, opportunities suddenly existed for young men to escape the heavy burdens of tending to livestock and tilling fields and to relocate to a metropolitan area to enter a profession requiring virtually no physical labour with the exception of lifting a pen to a ledger. Accordingly, the new class of accountants, who essentially redefined freedom as the elimination of toil, enjoyed elevated social status and attracted ever-increasing numbers to their ranks.

Exponential growth in the labor market restructured the national milieu. Rather than axiomatically planning to follow in the footsteps of their farm-bound fathers, the question ‘what shall I do for a living?’ now preoccupied the minds of urban and rural youth (51). Earning a self-sufficient wage or salary translated into personal independence and afforded unprecedented possibilities of material consumption. On days off, well-remunerated clerks could shop at A.T. Stewart, the ‘Marble Palace’ retail store in New York, enroll in classes at recently established business schools or read one of many available books on how to manage money. In observing in 1844 that ‘money […represented] the prose of life’ rather than literature or political participation, renowned essayist and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82) conceded to the baser realities of his cash-motivated country (84).

In Chapters Three, ‘Self-Making Men’, and Four, ‘Desk Diseases’, Zakim delves into the real and perceived occupational hazards faced by moderately- to lowly-paid clerks within densely populated cities. At dozens of boarding houses, bookkeepers broke bread with up to 300 other males and engaged in conversation and potentially ‘non-Christian’ behaviour such as gambling, drinking and/or using sex workers.

While conservative critics denounced the absence of community and church as detrimental to the moral upbringing of young and impressionable men, others decried the often-abysmal sanitary conditions of the streets, the dangerous levels of carbon dioxide, ammonia and sulphur emitted by gas-powered lights and the extension of working hours into the late evening (89-93). Far from the rigours of the farm, sedentary accountants, who plowed through numbers hour after hour, frequently complained of ‘headaches, dizziness, deteriorating eyesight, deafness’ and other ‘desk-diseases’ (122). In response, social reformers sparked movements aimed at ‘the emancipation of the clerks’ from the perils of their unnatural work environment (101). Beyond successful campaigns for the construction of mercantile libraries and gymnasiums as outlets for education and exercise respectively, health-conscious ‘experts’ launched zealous crusades against a relatively new phenomenon – overeating – by stressing the benefits of wholesome foods, advocating for dietary restrictions and condemning the pastry as an ‘instrument of self-destruction’ (130-36).

The fifth and final chapter, ‘Counting Persons, Counting Profits’, chronicles the widening adoption of statistics to measure the totality of American life. Subsequent to the landmark survey Report on the Subject of Manufacturers (1791) – ordered by the first US Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, and comprising the first detailed analysis of the state of the economy – both independent and government-sponsored studies turned to quantitative methods to assess the production of goods and services, mortality rates, agricultural trends, wages and weather patterns, among other elements of society. Although quantification often furnished an objective basis for evaluation for the purpose of setting policy, numbers could also be skewed or brazenly manipulated by elites. Commenting on the increasingly widespread utilisation of formulas and figures to bolster false claims, the novelist and humorist Mark Twain (1835-1910) famously exclaimed: ‘There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.’ Indeed, clerks, accountants and statisticians did ‘represent’ and ‘invent – economic order’ (185).

At the fin de siècle, the United States and its burgeoning army of pen-waiving clerks managed to overturn centuries of agrarian-dominated ideals by unleashing market-driven principles upon employers and employees and exalting the purveyors of commerce above polity. In adding a nuanced explanation of this monumental social transfiguration of the nineteenth century, Accounting for Capitalism: The World the Clerk Made succeeds in illuminating capitalism as a complex architecture – a joint project between industrialists, financiers, clerks and a revolution in social mores – that mobilised tens of millions to pursue an ‘American dream’ over paper trails and a materialistic concept of progress. As such, Zakim’s cogently argued monograph merits recognition for demonstrating the grand historical consequences wrought by the lesser-known enablers of a radical economic system.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

2 Comments