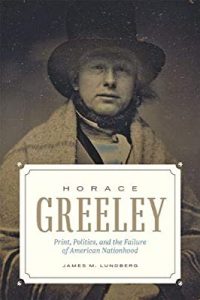

In Horace Greeley: Print, Politics and the Failure of American Nationhood, James M. Lundberg offers a new portrait of the nineteenth-century US public figure, Horace Greeley, the founder and editor of the New-York Tribune and an advocate for the anti-slavery North and emerging Republican Party. This rich history provides key insights into how the emergent conditions of American nationhood were both compelled and repelled by a media landscape unsure of its place in the construction and maintenance of American political discourse, writes Justin Harbour.

Horace Greeley: Print, Politics and the Failure of American Nationhood. James M. Lundberg. Johns Hopkins Press. 2019.

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

The American Civil War is perhaps the most fruitful ground for studies on the role slavery played in the construction of an American politics and nationhood capable of adequately advancing America’s revolutionary egalitarian inheritance. The New York Times’ 1619 Project, for example, recently advanced a reinterpretation of slavery’s central role in America’s construction that was met with strong disapproval by some of the foremost US historians. In another example, Matt Karp of Princeton University argues that the overturning of American slavery was the result of a democratic mass politics not previously seen in America and typically elided in mainstream histories of the era. These examples testify to the fact that debates over the role of slavery in the construction and reconstruction of America’s historical narrative are alive and well.

The American Civil War is perhaps the most fruitful ground for studies on the role slavery played in the construction of an American politics and nationhood capable of adequately advancing America’s revolutionary egalitarian inheritance. The New York Times’ 1619 Project, for example, recently advanced a reinterpretation of slavery’s central role in America’s construction that was met with strong disapproval by some of the foremost US historians. In another example, Matt Karp of Princeton University argues that the overturning of American slavery was the result of a democratic mass politics not previously seen in America and typically elided in mainstream histories of the era. These examples testify to the fact that debates over the role of slavery in the construction and reconstruction of America’s historical narrative are alive and well.

Into this fray steps James M. Lundberg’s Horace Greeley: Print, Politics, and the Failure of American Nationhood, in which Lundberg takes on the illustrative case of Horace Greeley, a nineteenth-century polymath. Lundberg’s analysis of Greeley is both lucid and revealing. Greeley was born in 1811, a time in which the fervour and passion to sustain the ideals behind the American revolution were settling into a period of attempts at self-actualisation. Greeley’s early life experiences were both typical and predictive. According to Lundberg, Greeley’s family was ‘downwardly mobile’ socioeconomically, rendering Greeley’s early life ‘rootless’ as the family traversed interior New England in the years of America’s Early Republic (20). As a child, Greeley demonstrated an unusual aptitude for reading and print. Combined with his upbringing in a Protestant culture that, according to Lundberg, ‘accorded great power to printed texts and the reading practices that brought them to life’(6), Greeley entered the turbulent world of the nineteenth-century printed press at the age of fifteen in 1826 (21).

The timing of Greeley’s entrance into professional media was opportune. Highly Protestant as it was, the America of the Early Republic embraced the printed word. Between 1800 and 1860, for example, the number of newspapers grew from 200 to over 3000. The nature of the burgeoning press was varied and often highly partisan. According to Lundberg, however, Greeley’s vision for the role of the media in the growing nation’s self-actualisation was informed by his Protestant ideals. The media for Greeley was an institution ideally ‘geared toward the instruction and unification of the people’ (20), interprets Lundberg, advancing ‘Enlightenment ideals of improvement, republican morality, and nationalism’ (21). Greeley earned occasion to enact his media philosophy in several New England publications before finally arriving in New York City in 1831. It would be in New York and its diverse culture that Greeley would forge his ideals into a news engine that advanced the cause of American nationhood.

Lundberg’s account of Greeley offers a thorough analysis of pre-Civil War politics that is simultaneously micro- and macrohistorical. Microhistorically, Greeley’s New York hosted eleven daily publications, printing close to a million pages by 1833 (22). The pervasive ‘humbuggery’ of New York’s media market in the 1830s and 1840s, antithetical to Greeley’s Protestant-inflected ideals about the printed word, compelled him to erect a more suitable publication for the public weal. Lundberg describes Greeley’s ill-fated New-Yorker as the intellectual foil to such humbuggery, as well as its ultimate succumbing to a media market set within an American society inflected with booms and busts of the economic and political variety. Lundberg describes how Greeley harnessed his belief in the role of print culture in contributing to overcoming these booms and busts (including an emergent, and at times violent, strain of nationalism) to realise a truer nationhood with his crowning achievement, The New-York Tribune. It would be at the Tribune that Greeley ultimately inserted himself into the macrohistoric trends of American nationhood. As a defender and critic of failed Whig politics to an observer of the emergence of the Republican Party, Greeley is portrayed by Lundberg as a man multidimensional, ambitious and unapologetically partisan.

Greeley’s macrohistoric influence is inextricably linked to the increasingly partisan nature of American politics in the years before the Civil War. By the 1850s America was squarely confronting the ramifications of its Westward migration and an economy built on enslaved labour. Lundberg concludes that Greeley’s self-identification as an heir to ‘American revolutionary ideals, battling those who would extinguish the flame of liberty’ accelerated his public persona as a deliverer and defender of American nationhood. The deliverance Greeley anticipated encouraged his disavowal of the American Whig party as a blithely centrist and corrupt organisation due to its ostensible deference to ‘slave oligarchs’ in the South. So too were Greeley’s ambitions propelled by ‘Bleeding Kansas’, an armed conflict that arose over the ban on the use of slavery in the development of land in the new territories by the Kansas and Nebraska Acts. These Acts were denounced by the Southern slave oligarchy for their effective repeal of the Missouri Compromise that had maintained a balance of enslaved and free labour in the increasingly tenuous union of states since 1820. The Kansas and Nebraska Acts thus inaugurated a new chapter of apprehensive ideological conflict over slavery.

Lundberg’s rich history observes Greeley embracing the necessarily partisan nature of anti-slavery politics via the ‘Bleeding Kansas’ conflict in the realisation of American nationhood. As Lundberg documents, Greeley’s support for the emergent Republican Party by 1856 was built on the conviction that the Republican Party ‘was not sectional, but national’ (99) and uniquely capable of uniting growing factions under one coherent political platform. Greeley’s use of anti-slavery politics to unify otherwise non-aligned factions under the banner of the Republican Party proved profitable for his Tribune and ideologically soothing. Greeley had, by the time of the Civil War’s onset in 1861, harnessed American partisanship to become a renowned believer in the cause of American unity through anti-slavery politics.

Greeley’s relationship to the problem of slavery in the construction of an American nationhood shifted from considering slavery marginal to this process to believing that any true American nationhood could only be realised by resolving the contradiction between the existence of slavery and America’s revolutionary ideals of equality in liberty and before the law. Greeley was not new to the concept of emancipation from political and economic injustice. Lundberg notes, for example, Greeley’s flirtation with Fourierist socialism, lending space in the Tribune for Charles Fourier to advocate for his brand of ‘association’ (56). Lundberg describes the years between 1854 and 1856 as a time when ‘the task [for anti-slavery Americans, such as Greeley] turned to creating a pan-Northern anti-slavery party – one that would unite splintering political factions and bridge fierce local loyalties’ (89). Greeley seized on this sentiment in 1854, using the Tribune to advance the cause of the newly established Republican Party.

By 1856, however, the cause of anti-slavery, the fight against slavery’s extension into the West and the conflict in Kansas pushed slavery to the front and centre of the drive to undermine the disproportional and unity-threatening power of a Southern slave oligarchy. According to Lundberg, on the precipice of the Civil War, ‘Greeley’s notorious call to allow ‘‘erring sisters to go in peace’’ was rooted in an unshakeable conviction that the claims of the nation were greater than those of a tiny, fire-eating cabal’ (117). Greeley’s ideological evolution, however, did not arrive without costs. ‘Fellow Republicans became infuriated with Greeley and his inconsistencies,’ Lundberg notes, as the perception of him being the puppeteer behind Northern anti-slavery radicalism ‘fueled the narrative of sectional conflict’ (110). It was slavery or anti-slavery, come what may, and Greeley had made his decision that anti-slavery was the key to realising American nationhood.

Nationhood was always the lynchpin of America’s future. Several events during the Civil War left Greeley in no doubt that there must be no compromise on the issue of slavery in the self-actualisation of a morally consistent American nationhood. The failure of Southern slaveowners to lay aside their financial interests in the cause of unity, for example, undermined Greeley’s belief in the liberal mainsprings of a nascent American character. After incurring a significant amount of scorn for his sponsorship of what became a Union failure at the Battle of Bull Run in 1862 – and the subsequent unburdening of ‘his soul to Abraham Lincoln’, as Lundberg puts it – the threat of Union loss and permanent schism in America made anti-slavery for Greeley the obvious and only cause with enough moral combustion to realise America’s revolutionary inheritance.

Lundberg notes that Greeley ‘denounced the president specifically for failing to enforce the Confiscation Acts’, while also engaging in ‘a mass public intelligence campaign – ‘‘a war of Opinion’’ – against slavery and the moral and cultural climate that sustained it outside of the Confederacy’ (125). President Lincoln’s embrace of anti-slavery in The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 was thus a balm to Greeley and his cause of nationhood through anti-slavery. Greeley’s reaction to Lincoln’s address included a reflection that ‘the United States (sic) future will be no constrained alliance of discordant and mutually repellant commonwealths […] Our Union will be one of bodies not merely, but of souls’ (130). As Lundberg appropriately interprets, Greeley saw the President’s co-sponsorship of anti-slavery as an indication that the nation’s moral and revolutionary rebirth was close at hand.

Lundberg’s history of Greeley does well to demonstrate the importance of the media in America’s move toward the emancipation of enslaved people and as a means toward American nationhood. Lundberg’s microanalysis of Greeley suggests that America demonstrated both a culture capable of constructing a nationhood and a simultaneous incapacity to do so. Through Lundberg we see how these internal contradictions within America were also robustly at play within Greeley. At times Greeley laid low his ideals in order to sponsor a pragmatic political response. Often, these ideological battles were countermanded by the economic imperatives surrounding the Tribune – a competition put into stark contrast when using his platform to advance a cause often at odds with capital’s interests in New York and America as a whole. Yet Lundberg clearly demonstrates an ideological continuity running through Greeley’s life: a belief in the moral capacity of America to advance justice and achieve its revolutionary democratic ideals through honest and adequate information.

Yet in the end, Greeley’s version of American nationhood was not realised. Though enslaved people were officially emancipated, slavery continued to plague America during reconstruction and into the twentieth century through Jim Crow and a federal government too hesitant to relive the trauma of war again. Nonetheless, through Greeley, Lundberg paints a rich picture of an American political economy coming to grips with its internal contradictions. Lundberg’s history provides us with key insights into the ways in which the emergent conditions of American nationhood were both compelled and repelled by a media landscape unsure of its place in the construction and maintenance of American political discourse. For Greeley wrote his adversarial story in the nineteenth century, and it is through him that Lundberg persuasively implores us to explore and understand America’s complex and turbulent history in this period. Take heed, Greeley calls through Lundberg: the national community is fleeting, and its seeds for rebirth can only be watered by those with the capacity and convictions to advance its cause.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Photography of statue of Horace Greeley, New York City (Alan Levine CC BY 2.0).