In Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora, Gayatri Gopinath offers an interwoven exploration of diaspora, visuality and queer studies, drawing on film, poetry, photography, memoirs and more as aesthetic practices of queer diaspora that invite new conceptualisations of affect, archive and region and the relations between them. This book directs an unruly gaze backward into queer regional archives, exposing new modes of curating, writing and scholarship that will prove critically important to future queer, affect and area studies, writes Polly Hember.

This review is published as part of a theme week focusing on LGBT+ scholarship following #IDAHOBIT2019. You can explore more of the week’s content here.

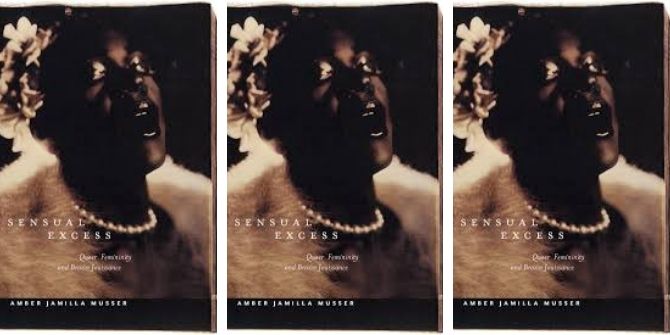

Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora. Gayatri Gopinath. Duke University Press. 2018.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

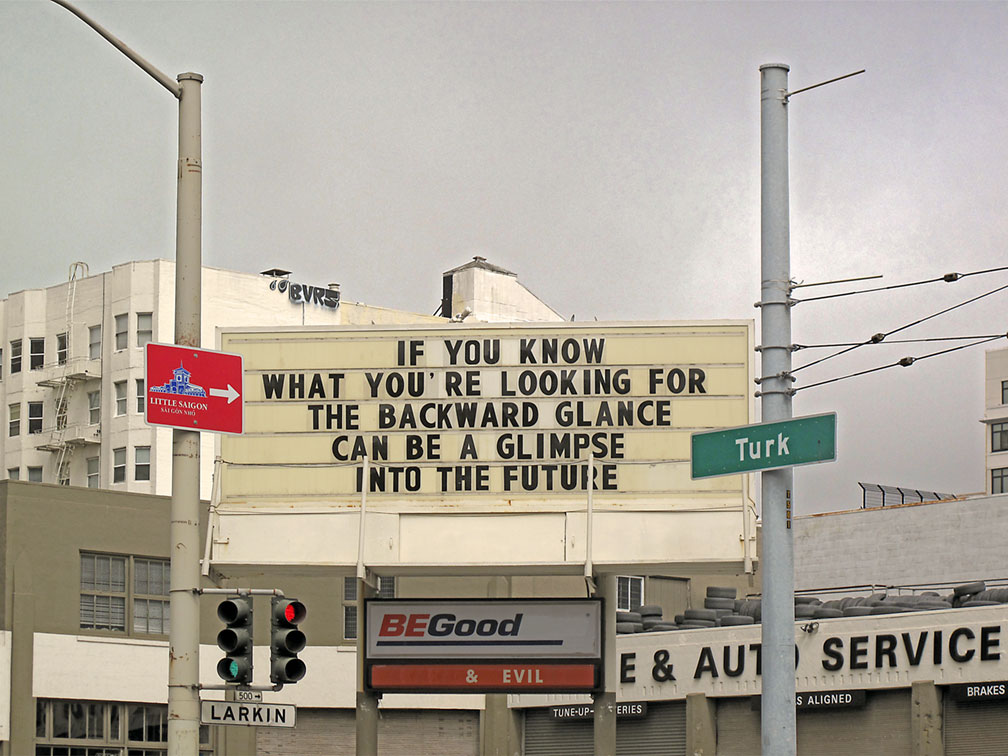

‘IF YOU KNOW WHAT YOU’RE LOOKING FOR’, a billboard reads in the multi-media artist Allan deSouza’s striking photograph ‘Future’, ‘THE BACKWARD GLANCE CAN BE A GLIMPSE INTO THE FUTURE’. These words convey how notions of backwardness, history and profound preoccupation with the past are indelibly caught up with thoughts on how the future will look. Gayatri Gopinath’s Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora explores how old images can perform new or alternative histories, deftly directing our reading of juxtaposed encounters between and within South Asian, Middle Eastern, African, Australian and Latinx visual artists and their aesthetic practices. These practices query conventional distinctions between local/global and indigeneity/diaspora. Gopinath exposes a new and necessary theory or ‘mode’ (88) for queer curatorial practice, which directs an unruly gaze backwards to regional archives and the past and is critically important for the future of queer, affect and area studies.

Unruly Visions explores visuality and diaspora through weaving in affect studies and queer theory throughout the text, to support detailed close readings of varied interdisciplinary works. These range from film (Aurora Guerrero, Ligy Pullappally), poetry (Agha Shahid), photography (deSouza, Chitra Ganesh, David Kalal, Tracey Moffatt, Seher Shah, Akram Zaatari), literary non-fiction and memoirs (Saidiya Hartman), watercolour painting (Ganesh, Moffatt) to installations and web-based artworks (Sheba Chhachhi, Ganesh, Mariam Ghani). Through Gopinath’s exploration of these artists’ use of visual culture – referred to as aesthetic practices of queer diaspora – alternative understandings of time, space and emotion are excavated from dominant histories, dictated by ‘happiness scripts’ overwritten with hetero- and homonormativity. At first glance, these artists and their work seem disparate and unrelated. However, Gopinath examines encounters between regional art collections by exploring issues of affect, queer disorientation and the quotidian that form linkages and expose differences. These collections, she argues, challenge conventional configurations of global/local area studies and instead propose interrelated, region-to-region cartographies that convincingly produce new mappings of space and sexuality.

Gopinath argues that queer visual aesthetic practices ‘transform regional archives into queer archives; they bring into the field of vision the memory of quotidian forms of queerness and gender nonconformity that mark the space of the region, as defined both supranationally and subnationally’ (5). Through looking backwards at the past, at the mundane, the excluded, the minor, the suppressed and the queerness in regional archives, Gopinath shows how unruly visions from the past actively challenge conventional critical theories of diaspora and nation. This is a two-pronged reconfiguration: firstly, one that looks backwards to reorient that ‘traditional backward glance’ of conventional theories of diaspora, often structured around a ‘desire for a return to lost origins’. Secondly, Unruly Visions looks to reconfigure spatial categories: it challenges the focus on the nation in conversations about diaspora by highlighting the importance of the region.

In looking at the landscape of regions, this book builds on the groundwork Gopinath established in her previous work, Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures (2005). This book offered an alternative model of visuality to read South Asian diasporic texts, claiming that the queer racialised body acts as a ‘historical archive’ that can reveal alternative histories, desires, sexual practices and narratives that are obscured by dominant historical narratives. In Unruly Visions, she expands on this research: ‘the aesthetic practices of queer diaspora evoke history without a capital H’ (8). She widens her scope and her unruly vision focuses the alternative model of visuality on minor sites and locations of queer possibility that exist in the region. In her queer excavation of diasporic aesthetic practices, she engages with submerged, obscured or forgotten modes of longing, despair, desire, embodiment and feeling that demand attention. This queerness that is occluded in the dominant ‘History’, she suggests, is the ‘conduit through which to access the shadow spaces of the past and bring them into our frame of the present’ (9).

Gopinath attempts to highlight the intimacies and shared affective, queer experiences of these juxtaposing aesthetic practices from a wide range of regions and temporalities. They all, she argues in her discussion of critic Lisa Lowe’s influential work on diaspora, respond to and have emerged out of the legacies of colonial labour relations that tie Europe, Africa, Asia and America to each other: these are the legacies of the dispossession of indigenous people(s), (post)colonial nationalisms and the diasporas of racialised, migrant labour. Gopinath manages this impressively, discussing a number of different artists throughout the book. She explores queer regions, using the subnational region of Kerala to show the two very different but shared affective, archival imaginings of Pullappally’s film Sancharram and Kalal’s visual art. Moving on to discuss queer disorientations in her second chapter, Gopinath challenges the trend in queer theory that sees ‘feeling backwards’ or disorientation as a form of staying lost. If queerness is a state of being out of place or disorientated in the landscape of heteronormativity, Gopinath illuminates the sense of backwardness as a way of the past’s haunting of the present – a haunting that will shape future pathways and avenues in that landscape.

Much work is being done to interrogate this feeling of backwardness or disorientation in the realm of queer studies. Unruly Visions resonates profoundly with Heather K. Love’s discussion of Odysseus and the sirens in Feeling Backwards: Loss and the Politics of Queer History: ‘

By being bound to the mast, Odysseus survives his encounter with the sirens: though he can hear them singing, he cannot do anything about it. What saves him is that even as he looks backwards he keeps moving forward. One might argue that Odysseus offers an ideal model of the relation to the historical past: listen to it, but do not allow yourself to be destroyed by it.

Gopinath asks us to ‘listen’ and, critically, look; to rearrange and reposition the historical past so perhaps different songs will be heard.

The discussion in Chapter Four of Zaatari’s curatorial work on the photographer Hashem El Madani is particularly convincing; it is his photographed figure, ‘Abed, a tailor’, who stares out defiantly and coolly from the cover of Unruly Visions. Gopinath illuminates how Zaatari’s curation, rearrangement and presentation of the Lebanese-born photographer El Madani’s aesthetic practices perform new histories, exploring the effects of war and violence, particularly in their fascination with the figure of the Lebanese resistance fighter (153), and also offer alternative, queer optics of same-sex desire in Zaatari’s archive in the photographs of bare-chested men and the ‘Abed, a tailor’ series (163).

In writing this book, Gopinath effectively puts into practice the new mode of queer curation that she argues for. She highlights ‘unexpected encounters’ between texts to expose new linkages between archive, region and affect, allowing the reader to feel the intimacies of multiple times and spaces that look backwards but push new ideas of criticism and curation resolutely forward. Unruly Visions demonstrates how, in curating and (re)positioning juxtaposed archives, regions and temporalities, new affective linkages are formed. Sitting at the intersection of queer, affect and area studies, this book peers backwards into queer regional archives with unruly, resistant and keen eyes that look to new modes of curating, writing and scholarship that all see(k) to confound conventional conceptions of local/global and metropolis/diaspora divisions.

Image Credit: Allan deSouza, Future, from The World Series, 2011, digital print, 12″ x 18″, courtesy of the artist and Talwar Gallery, New York and New Delhi. Thank you to Allan deSouza for giving permission to use ‘Future’ in this review. Images are provided courtesy of Allan deSouza and Talwar Gallery, New York and New Delhi, and should not be reproduced without the permission of the copyright holder.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.