In Contentious Rituals: Parading the Nation in Northern Ireland, Jonathan S. Blake offers a new examination of the complex phenomenon of Protestant parading in Northern Ireland, drawing on carefully compiled sociological and ethnographic data to argue that, in the words of his participants, what motivates the majority of paraders, musicians and spectators is not political, ethnic or religious chauvinism, but rather commitment to a longstanding cultural practice positioned as antipolitical. This is a nuanced and rich study, writes Nicholas Baker, that will be of great value to anyone interested in contemporary politics in Northern Ireland.

Contentious Rituals: Parading the Nation in Northern Ireland. Jonathan S. Blake. Oxford University Press. 2019.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

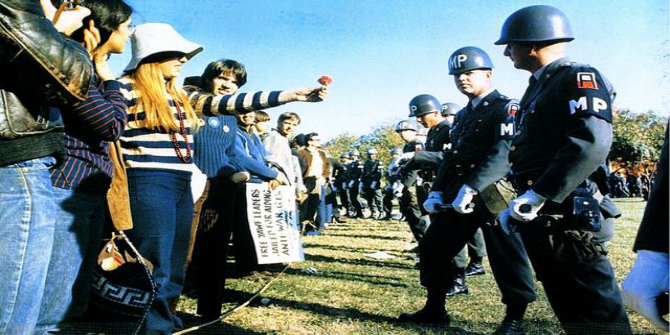

The existing literature on loyalist parading in Northern Ireland often situates Protestant displays of unionism within broader historical contexts of sectarian violence and intracommunal strife. To do so makes a great deal of sense: the Troubles, a rather anodyne term for a period of prolonged paramilitary and state violence over a period of more than thirty years, elicits strong, painful, often unresolved emotions among people in Ulster. Furthermore, one cannot help but be moved, in one direction or another, by the (in)famous traditions of Apprentice Boys commemorating the Siege of Derry, or Orangemen and blood-and-thunder pipe bands celebrating William III’s victory over James II at the Battle of the Boyne in Northern Irish towns and cities each year. The tradition of parading is therefore tremendously polarising, and the violence which often accompanies it has for many observers come to colour popular conceptions of life in Northern Ireland.

Jonathan Blake’s recent and most welcome contribution to the field, Contentious Rituals: Parading the Nation in Northern Ireland, offers important, timely and well-researched insights into contemporary parading which disrupt the dominant narrative that participants march to provoke, antagonise and intimidate Northern Irish Catholics in an ongoing effort to assert Protestant dominance and further entrench sectarian conflict. Blake uses sociological and ethnographic data carefully compiled over eight months in 2016 to argue that what motivates the majority of paraders, musicians and spectators is not political, ethnic or religious chauvinism, but rather an extended cultural practice. Blake’s most significant and nuanced finding is that participants see parading not as a political act, but as a cultural one: according to the author, the majority of paraders and spectators claim that these categories are mutually exclusive, and that culture and politics are not only juxtaposed, but are defined in contrast to each other (128). The author wisely does not go so far as to discount divisive motivations entirely, but nevertheless provides compelling evidence that loyalist parades in Northern Ireland, and Belfast in particular, are instances of anti-politics – that is, those who parade or watch from the sidelines consider their actions not only apolitical, but they also view parading generally as transcending politics and existing outside of such narrow categories (17).

This point raises an important paradox for Blake: how can actions which are so easily correlated with the cyclical nature of political, sectarian violence and harmful outcomes be construed as anti-political, cultural expressions by those who participate in parades? A passing familiarity with Northern Irish politics, for example, is enough to understand that marching to Drumcree Church in the company of an orange-bedecked pipe-band is unlikely to go unnoticed by Portadown’s Catholic community. Indeed, Blake notes that while disputed parades like Drumcree are a fraction of the total, ‘they dominate media coverage, public discussions, and the perceptions of many citizens and international observers’ (46).

Despite the choregraphed and predictable nature of the violence that often follows particularly provocative parade routes, enthusiasm for public displays of loyalism remains high in Northern Ireland. Nearly two-thirds of self-identified Protestants attend marches on 12 July alone, which marks the victory of ‘King Billy’ at the Boyne. Blake persuasively argues that although participants are aware that their actions are often perceived as inflammatory in many Catholic communities, they nevertheless proceed because of the ritualistic nature of the marches. Songs and melodies, sashes, intricate banners and even the presence of spectators are for many participants examples of intergenerational tradition and symbolic ritual, to the degree that most participants, according to Blake’s carefully collected quantitative data, do not associate anti-Catholic sentiments with parading (61).

Chapters Three and Four, in which Blake analyses the primary motivations for participation, are the strongest, most convincing and indeed provocative sections of his work. Building on his conception of anti-politics, Blake writes:

being apolitical is to be passively not political; being anti-political is to take an active and antagonistic stance against politics and the political. Things that are anti-political are not on the same spectrum as things that are political; there is an absolute difference of kind.

For Blake, anti-politics manifests in loyalist parading through ritualistic expressions of collective identity, tradition, social and emotional pleasures and forms of external communication in the form of invitations to spectate or participate (84).

Tradition, as Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger noted, is notoriously difficult to decode and often has much younger, nebulous cultural roots than is supposed by many of those who partake. Blake engages with this literature and more recent scholarly trends to argue convincingly that anxiety in Protestant communities has remained high after the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. Following the Agreement, Protestant hegemonic political power in Northern Ireland became untenable, and the ever-present spectre of loss that in many ways has defined and underwritten the perceived ‘siege mentality’ of Northern Irish Protestants was further entrenched (110). Indeed, the contrast between past fortunes and an uncertain future for Protestants in Northern Ireland is what makes the ritual of parading so contentious: the ‘memories and aspirations’ of participants are in direct conflict with those of most Catholic communities (5). These incongruous and competing forms of popular memory are, according to Blake, the main ideological sites of cultural struggle between the two groups, and function to maintain discrete personal and collective identities. Ironically, as Blake notes, anti-political displays which seek to express cultural homogeneity are inherently politically loaded spectacles: engaging in contentious cultural practices which putatively transcend politics is itself a political act that silences opposition by necessarily excluding significant segments of the population (136).

Contentious Rituals is of great value to anyone interested in contemporary Northern Irish politics, especially those who seek to understand the fraught, complex sociopolitical phenomenon of loyalist parading. Blake’s work, however, is not without minor flaws: given that the author’s research was conducted almost exclusively in and around Belfast, one wonders whether Parading the Nation in Belfast would be a more appropriate subtitle. The author can be forgiven logistical constraints which limited the geographic scope of his work, but the study most definitely would have benefited from incorporating data from other Northern Irish cities and towns. I am particularly curious to see how the author’s findings would compare to a similar ethnographic field study in Derry – a city whose very name is contentious, never more so than during parade season. Additionally, many historians of Northern Ireland may take issue with Blake’s choices pertaining to secondary literature. The author is a political scientist by training and his discipline’s most recent, cutting-edge work is well represented in copious footnotes; historians, however, may be perplexed at the author’s historiographical choices. Blake, for example, relies mostly on historical work published more than twenty years ago, and in some instances, over 40 years ago (notable examples include ATQ Stewart’s 1977 work, The Narrow Ground, and Richard Rose’s Governing without Consensus, published in 1971).

Despite minor issues, Contentious Rituals is a rich, engaging work that offers a fresh and welcome perspective on loyalist parading. Blake’s judicious use of his informants’ own words provides a unique, nuanced understanding of what motivates Protestants in Northern Ireland to take to the streets with sashes, banners and flutes, and provides compelling evidence that, contrary to popular opinion, for most 21st-century paraders, religious and ethnic bigotry is a statistically unlikely reason for marching on 12 July.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books

Image Credit: 12 July 2012 parade, Belfast (Adam Bishop CC BY SA 3.0).

1 Comments