In The Passion Projects: Modernist Women, Intimate Archives, Unfinished Lives, Melanie Micir unravels a queer feminist counterhistory of Modernism through women who have been not only writers, but also archivists, collectors, editors and curators. An ode to the value of feminist research and biography as a tool and method for revisiting the past through its original use of extensive archival material, this book is not only a key pedagogical resource, but a thought-provoking and enjoyable read, recommends Cristina Díaz Pérez.

The Passion Projects: Modernist Women, Intimate Archives, Unfinished Lives. Melanie Micir. Princeton University Press. 2019.

‘We must learn that authority and wisdom come in many forms, sexes, colors, shapes, and sizes. We must learn from one another and think again’ (Siri Hustvedt, 2019). Currently, research is encouraged to be interdisciplinary and diverse and researchers are expected to think laterally, especially when revisiting the past. Thus, we will be able to expand what has been coded as canonical or established knowledge as it occurs in literature. So, let me ask you: could you tell me any Modernist writer?

‘We must learn that authority and wisdom come in many forms, sexes, colors, shapes, and sizes. We must learn from one another and think again’ (Siri Hustvedt, 2019). Currently, research is encouraged to be interdisciplinary and diverse and researchers are expected to think laterally, especially when revisiting the past. Thus, we will be able to expand what has been coded as canonical or established knowledge as it occurs in literature. So, let me ask you: could you tell me any Modernist writer?

Time’s up. The odds are that you have thought of James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, T.S. Eliot, or perhaps Virginia Woolf, as examples of Modernist writers. If you are a bookworm or if you have read Gender in Modernism, you may have thought of women such as Jean Rhys, Naomi Mitchison or Rosamond Lehmann. But, regardless of your answer, what lies beneath my question is the fact that a feminist epistemology has been and is still necessary in literary and cultural studies to revise literary periods and unveil women writers, as Melanie Micir’s The Passion Projects: Modernist Women, Intimate Archives, Unfinished Lives stunningly exemplifies.

In her new book, Micir puts forward those genres that have been neglected, such as biographical acts and feminist projects. But above all, she unravels the queer counterhistory of Modernism through women who have been not only writers, but also archivists, collectors, editors and curators, and who are necessary to explain the intricacies and the diversity of such a historical movement.

The Passion Projects is therefore a Modernist recovery project on the blurring and possibilities of biography as a genre from a queer and feminist perspective. The book is organised twofold. To begin with, the volume is divided into four chapters that include different women whose biographical acts share common purposes, ranging from addressing future audiences, undertaking acts of resistance, reshaping Modernism to collecting. These are all positioned as feminist responses to the queer disinheritances and male predominance of literary historiography.

In turn, each chapter delves into pairs or groups of three women who have had an intimate relationship – whether erotic or not – such as Radclyffe Hall, Una Troubridge and Evguenia Souline, or Hope Mirrlees and Jane Ellen Harrison, constructing a queer feminist genealogy of influences while recounting parts of their Modernist lives. Thus, an outstanding contribution of the book is the fact that it is not only an academic volume, but it can also be read as a compendium of biographical insights into the lives of these Modernist women.

The first chapter, ‘Intimate Archives: The Preservation of Partnership’, opens with insightful comments on the importance of archival research ‘to make sense out of nonsense, to build a cohesive story of forgotten fragments, and to rescue marginalized historical narratives from their obscure and often damaged archives’ (18). Indeed, the value of manuscripts and photographs, and ephemeral writing such as letters and annotations, is signalled throughout the volume as being part of the construction and the self-representation of Modernist authors.

Authors become curators of archives of their partners and of their own biographical projects, as Micir analyses in the case of Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland: ‘In addition to the epistolary archive Warner collated and annotated after Ackland’s death, Ackland herself became increasingly dedicated to preparing versions of their lives for posterity’ (41). Micir highlights how, in this process, these women have shaped our understandings of their intimate archives by curating them. Thus, another of Micir’s achievements in this volume is addressing scholars to show the processes of research and recognition that can be found when investigating archives.

On the subject of research, raise your hand if you have ever been afraid of a blank page. Do not feel alone: this was also an issue for Djuna Barnes and Mirrlees. Paralysis when writing and a sense of failure are the two main issues raised in the second chapter, ‘Abandoned Lives: Impossible Projects and Archival Remains’. Micir delves into analysing the impossibilities of ending a biography about Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven in the case of her friend Barnes, and about Harrison by her lover Mirrlees. Despite their inability to succeed in completing these biographies, they conveyed acts of resistance by guarding the collections and leaving their imprint and lasting influence on them. This approach towards biographical acts and projects entails expanding the timing and identity limits of Modernist works, and it presupposes queering the Modernist archive by expanding their future possibilities.

Decentring Modernism and signalling its incompleteness regarding research is achieved in ‘Modernists Explain Things to Me: Collecting as Queer Feminist Response’, where Micir deepens her look into women who have been typically considered secondary characters: Margaret Anderson, Sylvia Beach and Alice B. Toklas, or, ‘An editor, a bookseller-turned-publisher, and a secretary-companion’ (80). Drawing on Kate Zambreno and her modernist memory project of recentring women, as explained in her book Heroines, Micir turns to unravel these three women as collectors, curators, chroniclers of Modernism, keepers, compilators and annotators. Thus, she expands the conventions of what fits into Modernism, and the book becomes a wondrous ode to feminist research and biography as a tool and method for revisiting the past.

The Passion Projects offers us an innovative take on Modernism in terms of the multiplicity of queer voices and genres that are exhibited. Nevertheless, the original use of archival material needs to be particularly extolled, since Micir emphasises archives, research and curation, and she even provides us with the venues of the collections that gather the personal projects of Gertrude Stein, Barnes and Vera Brittain, among others. The book will become a key pedagogical resource for the study of Feminist Modernist Studies due to its scope as well as the myriad of primary sources and the bibliography that it provides. Besides this, it is an easy-to-read and thought-provoking work that will appeal to a diverse audience. Whether you are interested in history, curation studies, literature or feminism, or you just want to have fun reading an enjoyable book, this can be your night-time reading.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

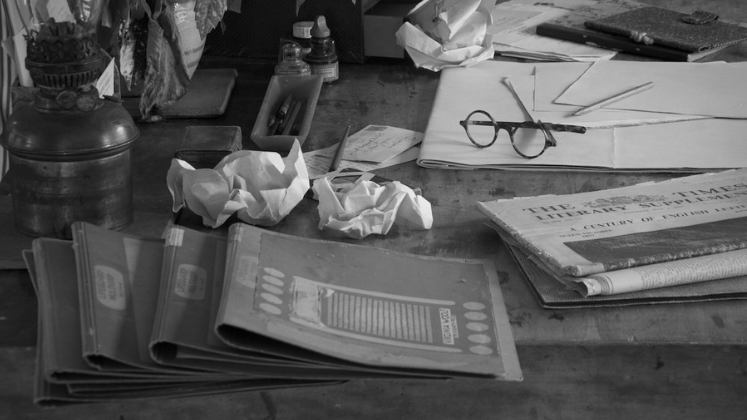

Image Credit: Photograph of writing desk taken at Monk’s House, Rodmell, East Sussex, the countryside retreat of Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf (Nick Lansley CC BY 2.0).