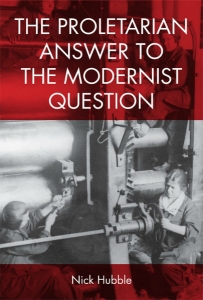

In The Proletarian Answer to the Modernist Question, Nick Hubble offers a convincing challenge to the persistent binary established between modernist and working-class literature in interwar Britain, arguing that the divide reflects a narrow view of political class consciousness. This is an insightful study, finds Stanislava Dikova, that seeks to show how remembering modernist legacies will contribute to the invigoration of political energy and resistance in the present.

The Proletarian Answer to the Modernist Question. Nick Hubble. Edinburgh University Press. 2017.

Nick Hubble’s The Proletarian Answer to the Modernist Question makes an insightful contribution to discussions about the relationship between the individual and society, which bears relevance to our contemporary political and economic context. With reference to the 2008 financial crisis, austerity, populism and the failures of neoliberalism, Hubble convincingly argues that a revision of one of the most persistent binaries in the cultural historiography of interwar Britain – that between modernist and working-class literature – is most timely. This well-established divide reflects a narrow view of political class consciousness and emancipatory power and contributes to the perpetual reproduction of oppressive forms of capitalist and patriarchal identification. Instead, Hubble argues, we should be seeking a different route to achieve a ‘post-scarcity emotional economy’ and imagine a future of social change, where more mutual and less oppositional social relations become everyday reality.

Nick Hubble’s The Proletarian Answer to the Modernist Question makes an insightful contribution to discussions about the relationship between the individual and society, which bears relevance to our contemporary political and economic context. With reference to the 2008 financial crisis, austerity, populism and the failures of neoliberalism, Hubble convincingly argues that a revision of one of the most persistent binaries in the cultural historiography of interwar Britain – that between modernist and working-class literature – is most timely. This well-established divide reflects a narrow view of political class consciousness and emancipatory power and contributes to the perpetual reproduction of oppressive forms of capitalist and patriarchal identification. Instead, Hubble argues, we should be seeking a different route to achieve a ‘post-scarcity emotional economy’ and imagine a future of social change, where more mutual and less oppositional social relations become everyday reality.

The Proletarian Answer to the Modernist Question examines the complex cultural mappings of the rebuilding of political consciousness in Britain following World War I. Hubble emphasises that the need to mobilise an aesthetic practice that remains open to examining questions of intersubjective identity as well as propelling social change was the paramount task facing British writers of the period (44). Taken separately, high modernism – represented by writers such as T.S. Eliot, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, and broadly preoccupied with introspective individualism (although this definition is strongly contested by modernists) – and proletarian literature – defined as works written by working-class authors like Walter Greenwood, Jim Phelan and Ethel Carnie Holdsworth, committed to a much more expansive political vision – fall short of this task.

For this reason, Hubble advocates a cautious approach to such rigid classifications and instead proposes a more communicative reading of the two aesthetic frameworks. His study takes the reader through a broad range of texts produced across the proletarian-modernist divide, including works by Naomi Mitchison, Ford Madox Ford, H.G. Wells, Katherine Mansfield, Ellen Wilkinson, Walter Brierley, Lewis Grassic Gibbon, John Sommerfield, George Orwell and Woolf. This wide selection of writers, Hubble argues, is united by the project of reconstructing human subjectivity to meet the demands of cultural modernism without dissolving the capacity for political action: ‘a proletarian-modernist outlook rooted in a political aesthetics of self-realisation and commitment to a post-scarcity society’ (48). That is, a social and emotional economy that harbours no inherent conflict between individual self-realisation and group welfare and is capable of supporting diverse identities and relationships (20).

Hubble’s illuminating discussion brings together at least three important strands of the study of British cultural and political life in the interwar period: modernist literature; working-class or proletarian literature; and women’s intellectual and political history. These often remain separate spheres of critical examination, despite their obvious interconnectedness. Instead, Hubble positions gender at the heart of his study, offering a number of illuminating readings of gendered forms of desire and performance and how they contribute to or ail political emancipation.

In Hubble’s reading of Gibbon’s novel Grey Granite (1936), which details the lives of Chris Guthrie and her son Ewan, Hubble comments on the limitations of the masculine proletarian viewpoint as expressive of the urban consciousness of the city. Gibbon describes a march organised by the workers at the engineering works where Ewan is apprenticed. During the procession, the men become animated by the passion of the march, which reminds them of World War I and leads them to attack the police. Their participation in collective action inspires them to feel a shared identity, similar to that in the army, imbued with a sense of agency that is generated not by everyday knowledge of their social conditions, but by the exhilaration produced by a momentary sense of unity and togetherness. Such experience of agency in reality is illusory, states Hubble, because the material circumstances of the protesters remain unchanged. This is linked to Walter Benjamin’s argument in ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936) that fascism relies precisely on such expressions of performative communal agency, which create a false sense of power whilst suppressing any attempts to restructure the social sphere.

Hubble further comments on Gibbon’s desire to launch a critique of masculinity as part of communist tactics and aestheticised forms of political action. Descriptions of men in various bloodied states and dreams of heroic death, Hubble writes, ‘expose exactly the inadequacies of the male fantasy of mutual betrayal and death which underpins homosocial relationships and maintains women as objects’ (126). This analysis offers important insight into the everyday mechanisms of class struggle and goes a long way to problematise the overtly masculine organisation of labour and union politics at the time, despite women’s participation and contribution.

In his critical methodology, Hubble draws on the work of sociologist Helen Merrell Lynd, who theorised shame as a productive affect to aid self-discovery. In Lynd’s view, experiences of shame, if confronted productively despite their inevitable painfulness, can ‘throw an unexpected light on who one is [. . .] Fully faced, shame may become not primarily something to be covered but a positive experience of revelation’ (Lynd 1958: 19-20). In this way, working through one’s feelings of shame incurred on the basis of gender or class identification can lead to productive individual realisations of the constraints placed upon one’s agency. It is through this framework, as well as the work of Carole Snee and Pamela Fox, that the intersection between gender and class struggle is brought into focus in the book. Fox’s argument in Class Fictions that the documentation of everyday working-class experience is a crucial aspect of any project contesting dominant culture is also very influential on Hubble, as is her assertion that ‘the impact of gender difference within this class-cultural context’ has been neglected by scholars (Fox, 22). Hubble tries to address this imbalance by analysing the formation and expression of desire and political agency in a number of female characters across his case studies.

However, despite Hubble’s efforts to defend Gibbon and Sommerfield against accusations of over-sexualising their female characters, questions remain regarding the political usefulness of building an understanding of women’s political agency on the back of their gender essentialist portrayals (In Sommerfield’s novel May Day (1936), examples of this include Martine’s desire for ‘nice curtains’ and aversion to her husband’s involvement in politics; Molly’s tenderness for ‘the sake of her lover’s pleasure’ despite failing to climax herself; Jenny’s ‘freedom’ from escaping factory life as the mistress of the senile and impotent Dartry; and in Gibbon’s Grey Granite, Chris’s habitual nakedness and her final retreat away from urban social life into the pastoral dream of Neolithic nature). Accounting for female political agency has to be more nuanced than disposing of the question solely through the means of pastoral escape and/or sexual liberation fantasies, as Gibbon and Sommerfield choose to do. Perhaps placing greater focus on women and queer writers, including authors of cross-cultural backgrounds, could offer a fuller picture of intersectionality and provide productive avenues for theorising women’s political agency.

Hubble concludes his insightful study of the formation mechanisms of individual and collective political consciousness by imagining the possible futures of the modernist-proletarian texts revisited in his analysis. These documents of everyday social life ‘far exceeded the capacity of state infrastructure and mainstream political imagination’ of their time and many of them were neglected and forgotten (200). It is Hubble’s hope that remembering the legacies of modernist-proletarian literature will help awaken the political energy to develop a space of resistance to the bourgeois patriarchal order and allow us to imagine a new liberated society.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: © IWM Q 28232. Original source: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205196408, licensed under IWM Non-Commercial Licence.