In Media and the Image of the Nation during Brazil’s 2013 Protests, César Jiménez-Martínez examines the mediatisation of the image of the nation during times of social unrest, focusing on the protests that took place in Brazil in 2013. Shedding light on the asymmetric power relations within the media environment and their impact on the coverage of the demonstrations, this book advances understanding of the mediatisation of protest, writes Helton Levy.

Media and the Image of the Nation during Brazil’s 2013 Protests. César Jiménez-Martínez. Palgrave. 2020.

What could massive protests tell about a nation?

What could massive protests tell about a nation?

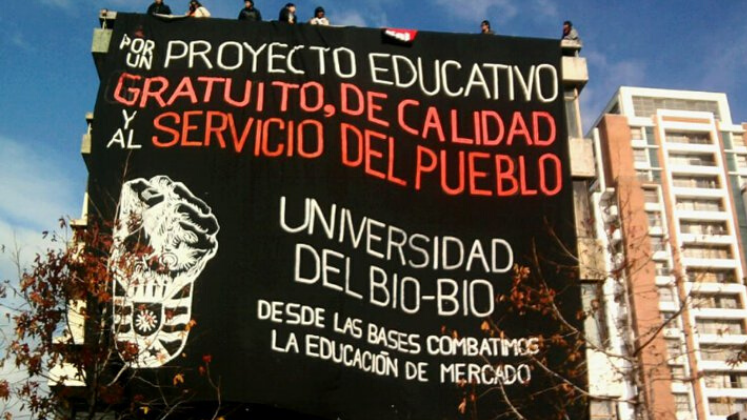

Crowds under lighting poles, crowds holding green-and-yellow flags, crowds on top of a white modernist building. Nearly a decade after these images first appeared, no definitive answer explains the enormous demonstrations that took Brazil by surprise in June 2013, nearly a year before the 2014 FIFA World Cup that Brazil was proudly hosting. These protests and marches, said to have involved 100 cities, became known as a moment of reckoning on many issues, not limited to public services, corrupt politicians, economic underperformance and violence.

The successive political crises that have happened in Brazil since then might have contributed to obscuring the explosiveness of that moment in 2013 and the way in which the media made it visible around the world. The televised catharsis had resized expectations about the country’s future and the fortification of its democracy, at least for those watching outside of Brazil.

This background underpins César Jiménez-Martínez’s book, Media and the Image of the Nation during Brazil’s 2013 Protests. The author sees the demonstrations — or the ‘June Journeys’, a name used by many to memorialise the event — as another opportunity to question the narratives that emerged out of the event’s media coverage.

For Jiménez-Martínez, mega protests, like those that also hit his native Chile in 2019, are interesting for the mediated visibility they offer the nation. The author focuses on the ability to project certain actors and images from these protests. Activists, PRs, journalists and government officials appear years later to give their accounts about these mediatised demonstrations. The study scrutinises the fact that these actors, while condemning the problems of Brazil, also remain very attached to a contested idea of the nation. Thus, the book sits at the crossroads of media studies, nation branding and the communication of protests and social movements.

Three chapters explain visibility as a confluence of strategies and conditions that these actors can follow. Visibility happens due to institutional protocols of awareness and response to episodes such as demonstrations: there are technological influences (such as social media), on one side, and normative or commercial pressures, mostly from the mainstream media, on the other. A frame analysis effort tracks the representation of Brazil in mainstream, official and alternative outlets. There are distinct emphases placed on aspects of the nation to highlight the harmonious, orderly or rebellious sides of the country, according to who reports it. To the government, of course, a heavenly image of the nation is fitting, in spite of the chaotic weeks of 2013.

Despite this clash of versions, the role of the mass media in narrating the event as a profitable mess is what stands out. Among the many interviewees, one senses the backstage of the coverage, as well as the ‘conditions’ for visibility. The chief correspondent of a US news agency said:

the world was interested [in Brazil] at that moment because a big sporting event was starting and that’s when they said, oh God, the sporting event being marred by protests, there’s our story. That’s when everyone flocked to it (144).

In the same way, ex-Brazil correspondent for the New York Times, Larry Rohter, points to the useful role of the foreign press for government officials: ‘They knew that maybe they weren’t getting attention from the President, so they thought, ‘‘oh, let’s talk to Rohter. We’ll put a story in The New York Times, and we’ll get some attention’’.’

Beyond these revelations, the author explains the dilemmas behind the Brazil brand in a much broader sense. He hints at the artifice of visibility:

Normative views on visibility—portraying it as necessarily a source of recognition or surveillance—are therefore inadequate to grasp its ambiguous, shifting and overall instrumental character, which facilitates its exploitation by different actors guided by contradictory aims (134).

He then concludes that: ‘‘‘Brazil’’ does not refer to an internal homogeneous group or ‘‘object’’, but rather to a shifting collage constructed and communicated across several mediated platforms, genres and technologies’ (12).

But what is visibility if not a normative expectation? Back in 2013, Jiménez-Martínez observed a threefold process that explains how journalists, activists and alternative media groups either replaced, adjusted or reappropriated the images and narratives of the event. These ‘strategies’ of mediated visibility ended up denying and blurring, but also evoked the idea of the nation as a troubled giant, which is how the mainstream press also wanted to represent Brazil.

Both realms, those of mainstream and alternative sources of information, coincided on many occasions. For example, a California-based activist who blamed Brazilian officials for the country’s simplistic images in the US says: ‘We do not need Brazil to look better for the world, we need our people to have food and health’ (93). This same quote suggests that the activist determination to state what the country should be like appears to confirm how naïve and wobbly Brazil’s official communications are. In this way, it is no wonder that the power of the alternative coverage of the protests is enhanced.

In 2020, a thought-provoking test for this visibility model lies in recent global media coverage that portrayed serious emergencies in Brazil, from the Amazon forest fires to the assassination of Marielle Franco. In a deeply unequal country, do the marginalised also depend on or relate to the conditions of mediated visibility seen in the 2013 protests?

Towards the end of the book, the author recognises the dysfunctional nature of the media environment, but not its role in forging the narrative of the protests as a special upheaval: ‘The mediated visibility of the June Journeys sheds light on the restrictive character of the media environment, as well as on the asymmetrical power relations between mainstream and alternative, Western and non-Western’ (179).

The book contributes by showing the many narratives that emerged after the 2013 protests, while confirming the central role of the mainstream media in building up expectations about the demonstrations. Taken together, the opinions of journalists about the protests, the content published in the press and the media climate depicted indicate a far more pragmatic reality. The book advances the debate on the mediatisation of protests by allowing each participant to show their own interests, which eventually turned the protests into a grand media event. As a result, what arguably began as student outrage over the cost of a bus ticket became a showcase of contradictions. The retreat of the protests, nonetheless, goes on in the record as part of a narrative of unaccomplished democratic goals.

Therefore, in the case of Brazil, massive protests, nationhood and global media visibility are aspects that continue to be strongly governed not by the nation itself, or grassroots groups, but by large media organisations that still shape the image of the nation to a great extent. Seven years later, the same Anglo-American press comes to proclaim the defeat of the ‘Brazilian spring’ as a way of dialoguing with itself and responding to its coverage’s own questions.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

In-text Image Credit: Protests in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, June 2013 (Mariano Vale CC BY SA 2.0).

Banner Image Credit: (Vitor Pamplona CC BY 2.0).