In Feminisms: A Global History, Lucy Delap offers a new and wide-ranging account of the global history of feminisms, drawing on an innovative range of sources to explore the rich, diverse and radical roots of feminist movements across time and space. Addressing the powerful contributions of feminisms while also examining their limitations, exclusions and complicities, this book is a triumph of feminist historiography that shows the innumerable different ways of imagining women’s freedom around the world, writes Jennifer Thomson.

Feminisms: A Global History. Lucy Delap. Pelican. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

In their 2017 Spring-Summer collection, a model walked down the Dior catwalk wearing a simple white t-shirt with a slogan in black lettering. ‘We should all be feminists,’ it said, the title taken from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s recent essay of the same name. The t-shirt was priced at £580. The fashion house continued this feminist angle in successive years, with later t-shirts adopting second-wave feminist slogans, such as ‘Sisterhood is global’ and ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’ These were soon seen in paparazzi shots of Hollywood celebrities, wearing the t-shirts as they left upscale restaurants or emerged out of expensive cars.

In their 2017 Spring-Summer collection, a model walked down the Dior catwalk wearing a simple white t-shirt with a slogan in black lettering. ‘We should all be feminists,’ it said, the title taken from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s recent essay of the same name. The t-shirt was priced at £580. The fashion house continued this feminist angle in successive years, with later t-shirts adopting second-wave feminist slogans, such as ‘Sisterhood is global’ and ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’ These were soon seen in paparazzi shots of Hollywood celebrities, wearing the t-shirts as they left upscale restaurants or emerged out of expensive cars.

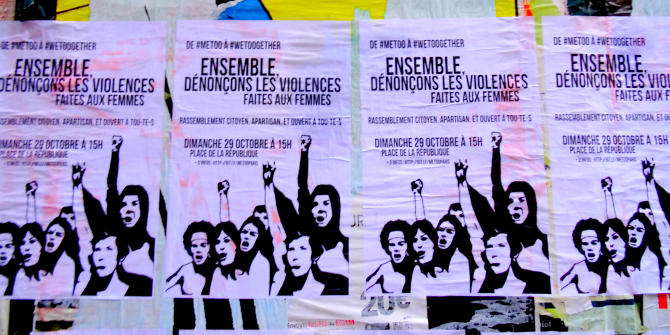

The appropriation of feminist mantras by a major fashion house and their rich clientele exemplifies the way in which contemporary feminism has often come to feel rather thin. In a world where Dior can market t-shirts costing hundreds of pounds in the name of feminism; where Ivanka Trump can define as feminist; where feminism is something now used to sell water bottles and mugs and posters on Etsy or to produce colourful GIFs and inspirational images on Instagram and Facebook – does it mean anything anymore? Does feminism now function as a means of buying and selling things? A way of making us feel good, and little else?

Set against this contemporary backdrop, Lucy Delap’s wide-ranging Feminisms: A Global History is deeply important. Her book acts as a key reminder that feminism has rich, radical and diverse roots, and cannot be reduced to a pithy slogan on a t-shirt. Feminism is, as she writes, ‘an alliance that spans more than half of humanity’, and indeed, ‘there may never have been such an ambitious movement in human history’ (3).

In her approach in this work, Delap moves beyond those who have used the explicit term ‘feminism’ to think more broadly about how gender as an organising principle of human society has been resisted and challenged. She addresses feminism as ‘an entry point to understand better how campaigns over ‘‘women’s rights’’, ‘‘new womanhood’’, ‘‘the awakening of women’’ or ‘‘women’s liberation’’ might have shared concerns and tactics’ (2-3). As such, we are taken on a journey that includes figures and events that would not have been classified as feminist at the time of their occurrence, stretching from colonial West Africa to Imperial Japan, and through an innovative use of source material ranging from political pamphlets to zines and songs.

Image Credit: Photo by Elena Mozhvilo on Unsplash

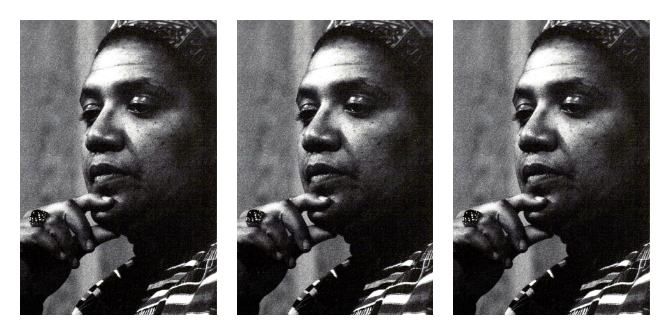

Delap uses a creative thematic framing, with the chapters’ organising themes at first glance bearing little to do with feminism or gender – ‘Dreams’, ‘Spaces’, ‘Objects’, ‘Looks’. Constructing the book thematically, she writes that her ‘aim is to offer feminist inspiration, showing how unexpected linkages and resonances emerge across different feminist generations and epochs’ (3). The first chapter (‘Dreams’) bounces from a turn-of-the-century Bengali feminist utopia, to feminist hopes at the advent of the Bolshevik Revolution, to the diaries of John Stuart Mill, ending finally at the poetry and thought of twentieth-century American author and activist Audre Lorde. The difficulties of threading together what are, at first sight, differing genres and time periods are easily overcome in Delap’s hands; what emerges is a fascinating insight into the way in which feminisms across time and space have responded differently to an enduring set of questions – ‘how and why society is organized, and why (some) men have louder voices, more resources and more authority than women’ (24).

Feminisms consciously aims to address the exclusions on which much feminist work is grounded. Delap wants to tell ‘the story of the limits of feminism, its blind spots and silencing, its specificities and complicities’ (3). As she acknowledges, ‘Feminist history has often been structured around a limited cast of mostly white and educated foremothers’ (15), and although these foremothers feature appropriately in her book (alongside Mill, the well-known cast of British suffragettes still gets a look in), the story of feminism is not allowed to revert to type.

The book instead approaches feminism from lesser studied angles. It begins with a letter penned in a newspaper on the Gold Coast (now Ghana) by a woman angrily decrying that ‘We Ladies of Africa in general are not only daily misrepresented but are made the foot-ball of every white seal that comes to our Coast’ (1). The chapter on ‘Spaces’ opens on familiar ground with the English political author Mary Wollstonecraft, but then moves to the Japanese feminist magazine Seitō, ends with tensions between white and Aboriginal feminists in contemporary Australia and features a long discussion of Nigerian Pan-Africanist feminist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti on the way. To describe this book as rich would be a considerable understatement, and Feminisms goes where much other mainstream work on the same subject has little interest to look.

Delap’s focus on feminism’s ‘exclusions’ doubtlessly leads to a less flattering (although far more truthful) picture of feminism than might sometimes be presented in rosier narratives. Western feminisms have long been understood to have a troubling relationship with colonialism and its legacies. In the chapter on ‘Ideas’, Delap describes the thinking of British activist Eleanor Rathbone (1872-1946) and her description of what she called the ‘Turk Complex’, her attempt to understand the psychology of male oppression over women. In doing so, Rathbone used an Orientalist language which was based on an understanding of ‘“the East” as a site of women’s subordination and confinement by men’ (74).

Elsewhere, Delap argues against the positive and united picture of women’s international organising sometimes presented in the historiography of the UN Conferences on Women. She describes the tensions between feminists of the Global North and South (and between lesbian and non-lesbian feminists within the Northern contingent) at the Mexico City UN Conference on Women in 1975, with indigenous feminist groups often at odds with a Northern feminism they saw as a ‘white, middle-class or ‘‘imported’’ political movement’ (256). Delap’s presentation through the book of these moments of tensions, prejudice and xenophobia are an important corrective to a mainstream vision of feminism which is singular and, at times, naïvely positive. As she writes in the conclusion: ‘We should be suspicious of attempts to flatten and simplify the landscape of feminisms, or to ignore its irredeemable ideological differences’ (343).

What emerges in this (forgiving the gendered language) masterful narrative is less a sense of progress, but rather feminism as a continually present form of Foucauldian resistance. Delap presents the last two centuries as a constant site of resistance and action against the dominant masculine status quo, with feminism always bubbling under the surface somewhere. She depicts feminism as a ‘mobile’ (14) entity, ‘a conversation with many registers’ (20), rather than a fixed set of ideas and actions: ‘We need not engage in a competitive struggle to identify the first, or the truest feminists’ (14) Such an exercise would not only be futile, missing the point that feminism has always been ‘malleable’ and ‘useable’ (14), but it would also overlook the more interesting question.

That question is, as this book implicitly reminds us at every turn, not what feminism means, but rather what has it done? How has it played out in different societies around the world? What art and literature has it created? What politics is it responsible for? How has it challenged and propped up power structures? How has it furthered human emancipation, progress – and suffering? It is these questions that Delap’s history asks and, as she shows us, the answers are wide-reaching, surprising and vivid.

Far beyond the thinness of much contemporary feminism, Delap reminds us of the powerful contributions that thinking about women and their rights have made to the world. Her book is a triumph of feminist historiography, but also, in its interconnected narrative, a powerful political argument about what feminism is (or should be). And indeed, as her title reminds us, feminism has never just been one thing. There were, and remain, innumerable different ways of imagining women’s freedom around the world. Far too many to be reduced to a slogan on a t-shirt.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.