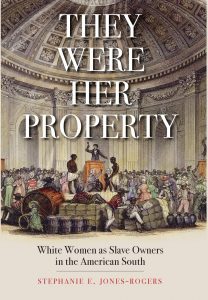

In They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers challenges the idea that white women were passive bystanders to the slave economy in the US, instead demonstrating their active participation in its structures of brutality and exploitation. Compellingly written and centring the testimonies of formerly enslaved people, this award-winning book is an important contribution to both historiography and contemporary politics as it adds to an ongoing conversation about the scope of women’s agency – and white women’s culpability – in the nineteenth century, writes Ben Margulies.

Please be aware that this review refers to acts of violence, including sexual violence.

They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South. Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers. Yale University Press. 2019.

When we talk about white supremacy in the United States, we often perceive a structure of masculine power. Discussing the planter class in The Half Has Never Been Told, Edward Baptist describes it as a macho culture, one that sought both economic and sexual domination. The Confederacy itself did much to promote the idea of martial valour contrasted with ‘pure’ white womanhood (actor Olivia de Havilland, who died in July 2020, essayed the latter as the character of Melanie Hamilton in the film Gone With the Wind).

When we talk about white supremacy in the United States, we often perceive a structure of masculine power. Discussing the planter class in The Half Has Never Been Told, Edward Baptist describes it as a macho culture, one that sought both economic and sexual domination. The Confederacy itself did much to promote the idea of martial valour contrasted with ‘pure’ white womanhood (actor Olivia de Havilland, who died in July 2020, essayed the latter as the character of Melanie Hamilton in the film Gone With the Wind).

This idea of white women as innocent and powerless has had baleful consequences. One explicit goal of white supremacy was the ‘protection’ of white women from Black men, and many lynchings and race massacres had their origins in accusations about African-American men and boys assaulting or accosting white women (including the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, the Rosewood massacre of 1923 and the brutal murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955). In Bring the War Home, Kathleen Belew relates how white supremacists used the trope of innocent white womanhood to sway juries in the 1980s; similar tropes have populated white-extremist propaganda.

In They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers takes aim at the myth of white women’s innocence. She rejects an established view that women in the antebellum South ‘had little to do with enslaved people beyond the household’ and ‘were not adept at slave or plantation management unless extenuating circumstances […] compelled them to be’ (xv). Instead, Jones-Rogers, Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley, places women in a central role in the narrative of white power in the United States. She focuses on the white women in the early Republic who actively held African Americans captive, who dictated their daily lives and who fully participated in the brutality and exploitation of slavery in the United States. In doing so, she challenges women’s presumptions to innocence in the unholy business of racialised power. As she concludes: ‘Southern white women’s roles in upholding and sustaining slavery form part of the much larger history of white supremacy and oppression […] they were not passive bystanders. They were co-conspirators’ (205).

Jones-Rogers explores the life of the Southern woman slaveholder from birth to marriage and, to an extent, into death as well, examining their wills and estates. She describes in aching detail how Southern households reproduced slave society. Southern children of both genders grew up watching their parents exert mastery over Black people, and then mimicked these behaviours. The book’s first chapter begins with Lizzie Anna Burwell, aged three, demanding her father ‘cut Fanny’s ears off’ and acquire a ‘new maid from Clarksville’ (1). Parents gave children enslaved people as gifts; enslaved people had to call their owner’s children ‘master and mistress’ (5-6).

One of the signal accomplishments of They Were Her Property is to explain just how women could actively own property in the antebellum South and thus claim ‘property’ in human beings. Formally, the common law did not recognise the right of married women to property, under the doctrine of coverture; a married couple had a single legal personality, which belonged to the husband. In Stephanie McCurry’s works, Confederate Reckoning and Women’s War (which I also reviewed on LSE Review of Books), coverture mimics the private government slaveholders exerted over African Americans; women had limited legal and political status, and whatever claims they made to such faced considerable resistance.

Jones-Rogers acknowledges that coverture was often a real constraint for married white women (27). However, she argues that Southern families often ignored or circumvented its strictures. Families could transfer property to daughters or other women relatives that would remain separate as a condition of the gift. Southern women could and did draw up what we would now call prenuptial agreements, or ‘deeds of gift, deeds of trust and wills that granted [the wife] control over all property she already owned or would acquire during her marriage’ (31). In Louisiana, women could petition the courts for separate marital estates should their husbands demonstrate imprudent financial management (35-37). One gets the impression that Jones-Rogers and McCurry are describing different structures that coexisted – a real patriarchy alongside a real apparatus of white women’s legal and economic power. The next question is how far each extended, cooperated and conflicted with each other.

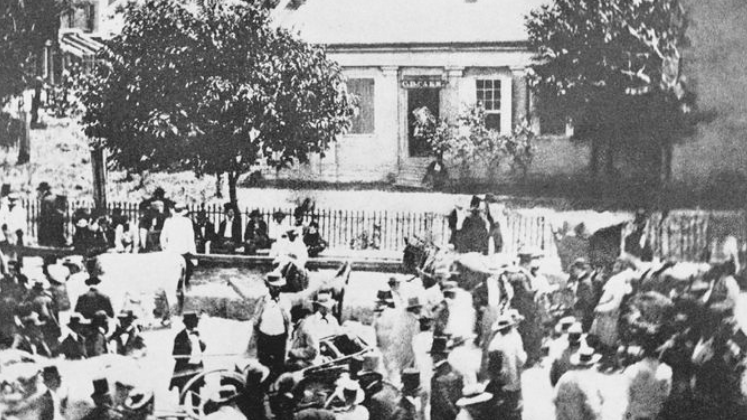

Much of They Were Her Property examines the role of white women in the human trafficking of enslaved people. In imagining white women as delicate and sheltered, some historians have claimed that they did not attend slave auctions or markets and had little role in the commerce in human bodies. This was not the case: ‘Travelers, slave traders, city officials and enslaved people all attested to the presence of white women in nineteenth-century slave markets’ (127). Women also bought and sold human beings from their own homes, often within local social networks or from itinerant traders. Some did business as slave traders, or fronted capital to men who did so, like Mathilda Bushey (144-46).

White women helped create a whole market in enslaved wet nurses, the subject of They Were Her Property’s fifth chapter. ‘White mothers determined whether they could withstand the physical toll breast-feeding imposed upon them […] Consequently, they were the ones who decided whether to borrow, hire, or buy an enslaved wet nurse, even if a man might finalize the transactions in the slave market’ (122). This allowed white mothers the freedom to pursue social lives or compensated for a physical inability to breastfeed their children.

White women were also fully implicated in the physical and sexual brutality of US slavery. The book describes mistresses so violent that their husbands had to restrain them (72-73). White mistresses often ‘invested’ in enslaved women in the hope their captives would bear children; Henrietta Butler told the 1930s Federal Writers’ Project interviewers that her mistress, Emily Haidee, had forced her and her mother to have sex with enslaved men (21). Masters also used rape to ensure a supply of women to serve as wet nurses (106-108). Other times, they hired women who had lost babies through miscarriage or infant mortality, dismissing the nurses’ grief and pain as ‘sulking’ (121). Some white women ran brothels staffed by enslaved people (146-49). One of the most chilling single stories involves Rose Russell, whose mistress asked which parent she loved the most. She said her father, and the mistress promptly sold her mother (135).

In her final chapters, Jones-Rogers looks at how women slave-owners faced the US Civil War and emancipation. She gives an excellent overview of the Union’s complicated and highly legalistic approach to emancipation (152-57), including the Confiscation Acts and the Emancipation Proclamation. In her Civil War chapter, Jones-Rogers shows how women contested emancipation, sometimes by telling Union authorities that they were loyal; she locates women slave-owners seeking compensation when the US ended slavery in the District of Columbia; and she finds evidence of women carrying their enslaved ‘property’ away from war zones, a practice known as ‘refugeeing’.

After the war, she finds white women negotiating labour conditions with freedpeople, and trying to maintain control of African-American children as ‘apprentices’. A few white women petitioned President Andrew Johnson for pardons, citing their losses in human property as a way of gaining sympathy (Johnson was vocally racist). She also briefly discusses how former mistresses attempted to (re)cast slavery as an opportunity to ‘buy, rule over, Christianize and civilize people of African descent’, an enterprise deemed to be so worthy that Letitia Burwell, author of an 1895 memoir on antebellum Southern life, thought African Americans should commemorate ‘the landing of their fathers on the shores of America’ (201). (Ironically, this is exactly what the 1619 Project, launched under the aegis of The New York Times, seeks to do, though for precisely the opposite reasons.)

Jones-Rogers draws on many sources, including Southern newspapers, court records and white women’s diaries. One of the major sources for her work is a series of interviews conducted in the 1930s with living former enslaved people, which were collected by the Federal Writers’ Project as part of the New Deal. These testimonies corroborate Jones-Rogers’s other evidence, but more importantly, they place enslaved people at the centre of Southern history and the history of slavery. She often turns the narration over to the interviewees, incorporating their reminiscences into the text and structuring sentences to identify them first. Jones-Rogers also describes how enslaved people attempted to navigate the world of slavery themselves, learning about market conditions, property laws and demands for skills in a bid to win freedom. Some tried to buy their own freedom, which was difficult since enslaved people could not legally make binding contracts (96-100). One enslaved woman, Winney, sued for her freedom in 1844, informing a Kentucky court that her late mistress’s marriage contract had provided for Winney’s emancipation upon her mistress’s death. She was successful (38).

The book is compellingly written and rich with anecdotes, though sometimes Jones-Rogers neglects to tell readers exactly where or when a particular event occurred. They Were Her Property is a primarily qualitative text; we are not presented with figures on the number of women slave-owners, the proportion of slave-owners who were women or the proportion of married women who had separate title. This data may not exist or may not have been compiled; in its absence, it is sometimes hard to grasp how common women’s participation was in ownership and commercial roles.

Ultimately, They Were Her Property contributes to a broader argument about women’s power that is both important for historiography and for contemporary politics. The book adds to an ongoing conversation about the scope of women’s agency – and white women’s culpability – in the nineteenth century. It also reminds us that even today, the intersection of race and gender can reproduce the oppression of women by women.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Photography titled ‘slave auction on Cheapside, Lexington’. NYPL catalog ID (B-number): b11672871. Photograph courtesy of New York Public Library, no known copyright restrictions.