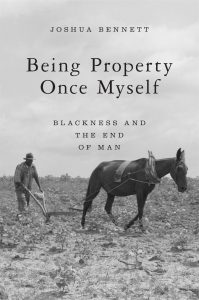

In Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man, Joshua Bennett explores how African American writers have forged a tradition that works through the figure of the non-human animal in order to assert and enact radical challenges to oppressive structures, contesting the violence of anthropocentrism and antiblackness and providing tools for conceiving of interspecies relationships anew. Carefully constructed with a lyrical lilt to its sharp analyses, this book is an important contribution to the emerging space in which black literary studies, animality studies and ecocriticism converge, writes Lydia Ayame Hiraide.

Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man. Joshua Bennett. Harvard University Press. 2020.

Joshua Bennett’s debut book of literary criticism, Being Property Once Myself, is a gripping work which examines works of black authors from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The book is framed through an interdisciplinary approach which embraces black studies, affect theory, ecocriticism and animality studies. At 189 pages excluding notes and acknowledgements, it is relatively short, and Bennett’s lyrical lilt in his sharp analyses makes for a thorough yet accessible read.

Joshua Bennett’s debut book of literary criticism, Being Property Once Myself, is a gripping work which examines works of black authors from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The book is framed through an interdisciplinary approach which embraces black studies, affect theory, ecocriticism and animality studies. At 189 pages excluding notes and acknowledgements, it is relatively short, and Bennett’s lyrical lilt in his sharp analyses makes for a thorough yet accessible read.

The careful and artistic construction of the text makes it obvious that alongside his academic work, Bennett is also a poet by trade. The work boasts beautiful yet lucid rhetorical flourishes, such as when he asks what black authors create ‘when they are willing to engage in a critical embrace of what has been used against them as a tool of derision and denigration, to leap into a vision of human personhood rooted not in the logics of private property or dominion but in wildness, flight, brotherhood and sisterhood beyond blood?’ (4). Throughout the entire book, the author’s reading of the literature he engages with is itself brilliantly literary in style.

The central argument of this interdisciplinary study locates the violence of anthropocentrism and antiblackness within each other, arguing that African American writers have forged a tradition which works through the figure of the non-human animal in order to assert and enact radical challenges to oppressive structures. In his introduction, Bennett sets out to elucidate ‘the ways in which the black aesthetic tradition provides us with the tools needed to conceive of interspecies relationships anew and ultimately to abolish the forms of antiblack thought that have maintained the fissure between human and animal’ (4), a goal firmly achieved by the text.

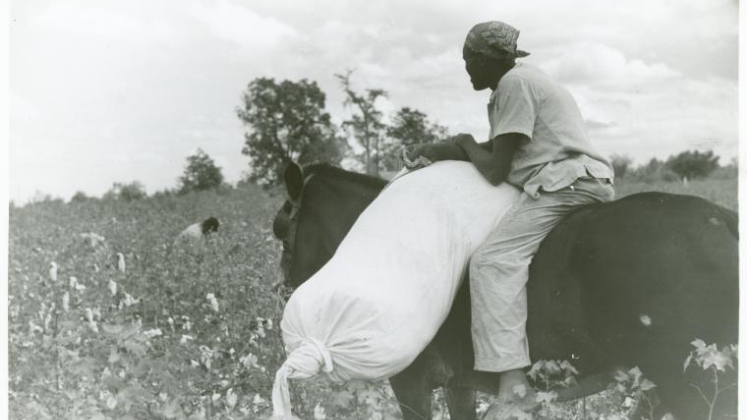

Organised into six chapters, each title is given by the non-human animal the chapter concentrates on. Bennett thinks through the figures of the horse, rat, cock, mule, dog and shark. Each animal is located in key contemporary African American literary texts, ranging from the works of Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) (Chapter Three, ‘Mule’), Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon (1977) (Chapter Two, ‘Cock’) to Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940) (Chapter One, ‘Rat’). It is this latter chapter focusing on black death and suffering which provides the most forceful and convincing black ecocritical literary analysis of the book.

Rejecting a politics of propriety or respectability, the first chapter uses Wright’s work to draw out the significance of black life, death, suffering and sociality through the figure of the rat. Bennett begins this discussion by engaging with R.J. Putnam’s Mammals as Pests (1934). He convincingly deconstructs the notion of rat as ‘pest’, as he exposes this ascription of undesirability to be rooted in capitalist logics of ownership and private property. In Wright’s text, the rat is thus identified as a figure with the capacity to disrupt white capitalism, and it is for this disruptive force and energy that the rat is deemed undesirable. Bennett articulately draws links between this energetic ‘ratness’ and the radical dynamism of blackness and black fugitivity. This link between the rat and blackness serves to emphasise the puissance of black sociality and black fugitivity, forces which are rooted in how ‘black folks survive even when they are outcast and outgunned and outlawed and outstripped, how they nonetheless go about living through the everyday’ (57).

Considering the pervasive construction of the rat as undesirable, Bennett’s choice to discuss blackness through, rather than against, what he calls ‘ratness’ signifies his capacity to critically lean in to the problematic. It would be easy to maintain the figure of the rat with the objectionable and thus call for a divorce in associating black life with such an animal. Yet, the analysis follows a complex route that thus proposes a ‘poetics of persistence and interspecies empathy’ (5), which ultimately rejects the human-animal divide through a radical model of blackness. This creative yet careful leaning in ultimately foregrounds the propensity of black authors to imagine and construct alternative worlds to the one in which we live, the one in which both the black experience and non-human animal experience are constantly permeated by violence. In this sense, then, the author is clearly not afraid to, as Donna Haraway might put it, stay with the trouble. Bennett’s insistence on black fugitivity points to a spirit in which other futures are possible, that can be arrived at by identifying and moving through ‘alternative models for thinking blackness and personhood […] in the present day’ (13).

In other chapters, especially ‘Mule’ and ‘Cock’, Bennett develops what can be seen as an intersectional analysis of black literary engagement with animality. He sensitively brings aspects of class and gender into his analysis. In his engagement with gender in particular, Bennett rejects the use of ‘gender’ as a synonym for women. Instead, he carefully examines the construction and function of both black masculinities and femininities as co-constituted. For example, Chapter Two looks at Morrison’s use of birds and flight in Song of Solomon as a provocation that sparks reflection on how black men are constructed in a social world and the tricky relationship between this construction and the inner yearnings of black men themselves. These reflections are always situated in relationship to black women and black femininity, emphasising the co-constitutive relationship of gendered difference and commonality.

In the same chapter, an interview which took place in 1984 between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde is brought in. Bennett observes that they ‘do not and perhaps cannot fully comprehend each other’s struggles at the level of experience, largely because there is a fundamental difference at play in terms of how their respective battles against patriarchy are structured, a difference that requires something other than an uncomplicated vision of black empowerment that would elide gender particularity in the name of racial uplift’ (109). This insight frames Bennett’s approach to marginalisation, which he understands as multiple and complex. He rejects the homogenisation of black experiences in the same spirit of the Combahee River Collective, of which Audre Lorde herself was a part. It proves to be more interesting and more generative to engage in this simultaneously gendered and raced analysis, for this approach allows us to reflect on the complexity of intersecting structures of violence in perceptive and expansive ways.

Particularly towards the end of the book, there are brief moments in which Bennett’s engagement with theorists such as Jacques Derrida or Jacques Lacan can feel a little dense, particularly if the reader is not familiar with postmodern ideas. This is at no detriment to the book’s overall argument, however, and is rather a reflection of the controversial debate around the accessibility of postmodernism more generally.

Crucially, Being Property Once Myself treats each text of the US black literary canon with a profound respect. In the context of our era, Bennett’s book is important. It adds to a growing body of critical work that tackles social issues in relation to the realm of ‘nature’, pushing back simultaneously against the whiteness of both literary studies and ecocriticism. Putting forth a strong argument which articulately locates antiblackness within the discursive treatment of non-human animals and the environment, the book is a significant contribution to the emerging space in which black literary studies, animality studies and ecocriticism converge. Certainly, the work is an important cultural text which engages with the junctions of the climate and environmental crisis, anthropocentrism and the violence of social marginalisation upon which US society, amongst many others, is founded.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: ‘African American cotton plantation worker, hired as a day laborer, riding a mule and holding down a sack of cotton in the cotton field at Nugent Plantation, Benoit, Mississippi Delta, Mississippi, October 1939.’ Image courtesy of New York Public Library (Public Domain).