In Occupied America: British Military Rule and the Experience of Revolution, Donald F. Johnson offers a new account that explores the everyday experiences of American civilians living under British military occupation between 1775 and 1783. Drawing out the ambiguities, compromises and complexities of occupied life for ordinary people, this is a well-researched and insightful book that contributes to a fuller understanding of the American Revolution, writes Mark G. Spencer.

Occupied America: British Military Rule and the Experience of Revolution. Donald F. Johnson. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

In a letter between two former US Presidents, John Adams, writing to Thomas Jefferson in 1815, defined the American Revolution this way: ‘What do we mean by the Revolution? The war? That was no part of the Revolution; it was only an effect and consequence of it. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people, and this was effected from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen years before a drop of blood was shed at Lexington.’ Donald F. Johnson, in this well-researched and insightful book, begs to differ. For many American colonists, he maintains in Occupied America, the Revolution played out in their minds and hearts from 1775 to 1783, during eight years of warfare, in the midst of British military occupation.

Take physician William Tillinghast. This devout Quaker, a one-time medical student of Benjamin Rush — Philadelphia’s most celebrated doctor and a signer of the Declaration of Independence — was apathetic to the Revolution when British troops occupied his city of Newport, Rhode Island, in late 1776. Tillinghast treated British soldiers for a litany of ailments — as his manuscript Physician’s Book documents — and he ‘socialised with the British military and their loyalist allies’, including in the Redwood Library; he was elected librarian in 1777, during occupation. With time, though, Tillinghast became disillusioned with the British. ‘Moved by the plight of his patients, his family, and his coreligionists, by the end of Newport’s occupation Tillinghast had abandoned his allegiance to the British cause’; he was ‘ready to embrace revolutionary rule’. Tillinghast was not alone. Others experienced similar transformations.

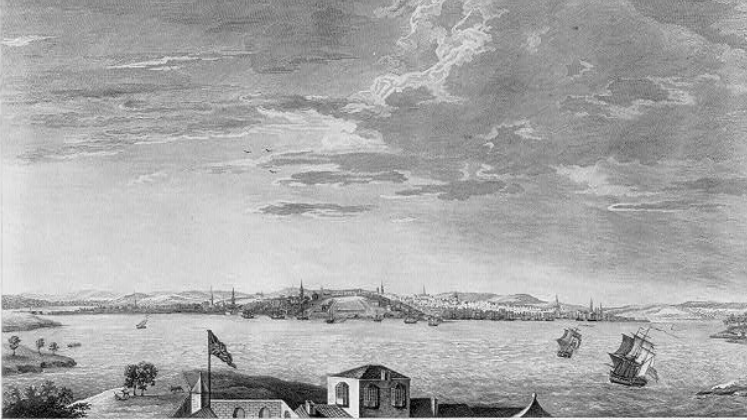

During the War, Britain occupied six major cities: Boston, New York, Newport, Philadelphia, Savannah and Charleston. In each — period maps are reproduced, courtesy of the William L. Clemens Library — ‘local residents incorporated British soldiers into the rhythms of their everyday lives’. British troops, Johnson argues, did not occupy tranquil American cities. Pre-Revolutionary tensions had played out in localised conflicts pitting colonial royal authorities against revolutionary Committees of Safety that had been instituted to take power away from them. With British occupation, day-to-day intimacy between American colonist and British soldier ‘served to cleave urban populations from their loyalty to the Crown’. Yet, some remained loyal. We learn about the wartime daily lives of men like Andrew Elliot, James Simpson, William Tryon and Joseph Galloway.

Those elite four we meet through Ambrose Serle, personal secretary to Britain’s naval commander in the war against America, Admiral Lord Richard Howe. Among Serle’s official duties was restarting Hugh Gaine’s New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, a newspaper to which Serle and others contributed loyalist propaganda. But Serle’s ‘journal’ illuminates his unofficial duties too. These encompassed ‘late-night drinking sessions with a vast array of well-to-do loyalists’ —including Elliot, Simpson, Tryon and Galloway, with whom Serle mingled in the course of a single week in May 1777. These four figures assumed leading roles for the occupying British. Elliot, a one-time tax collector, would help run New York City along with Simpson who later took that experience to occupied Charleston. Former colonial governor Tryon was recruited as a general in a loyalist corps. Galloway, a delegate to the First Continental Congress who counted Benjamin Franklin among his close friends, was installed as Philadelphia’s Superintendent of Police, essentially heading the occupation government. So, why did the British occupations fail? Johnson’s answer lies in ‘the experiences of ordinary people within the occupied cities’.

For thousands of American civilians, Johnson argues, military rule brought the possibility of change for the better. That was so for the many African Americans who sought freedom from slavery behind British lines. It was also the case for the countless ‘poor whites’ and ‘middling craftspeople’ who found gainful employment with an occupation that ‘restored American ports to the larger economy of the British Atlantic’. Still, there were grave risks. Occupation was precarious and the timing and consequences of British evacuation unknowns.

What of the impact of occupation on American women? Some ‘found empowerment’ in the turmoil of a war that shook up social norms of gender, writes Johnson. Others found agency in curious ways. Consider the Meschianza. Held outside of Philadelphia in the summer of 1778, the Meschianza was organised as a gala send-off for the Howe brothers’ departure from Philadelphia for Britain. Organised by British Major John André, the celebration ‘consisted of a sailing regatta down the Delaware River, a medieval tournament complete with triumphal arches, and a dinner, ball, and fireworks display afterward at a local country mansion’. Johnson describes how the British officers, ‘dressed as medieval knights […] jousted with one another for the favor of Philadelphia women dressed in mock-Turkish garb’. It must have been quite a spectacle. London’s Gentleman’s Magazine thought so. For Johnson, Meschianza displays how Philadelphia’s ‘elite women […] transformed themselves and their circumstances under occupation’ and ‘throws into sharp relief the slow process of integration that occurred in countless dining rooms, coffeehouses, and church halls throughout occupied America’.

Stronger forces worked against integration of British occupiers into American life. Food shortages, dwindling fuel supplies, insufficient housing: herein lay the seeds of discontent. This ‘lack of everyday necessities plagued territories under military rule’. British plunder made it worse. Increasingly, Americans living under occupation came to ‘question their faith in royal authority and the benefits of a reunion with the empire’. Wavering affiliations, though, were hard to spot. Those living under British occupation had learned ‘to obscure their true political beliefs’. They were ‘adept at espousing different beliefs to different people at different times’, as Elizabeth Drinker’s famous diary of daily life in occupied Philadelphia illustrates. The prospect of peace blurred things further. For some, like British collaborator Tench Coxe, American victory involved erasing evidence and laying low. Narrowly avoiding charges of treason, Coxe was later elected to Congress and later yet appointed Assistant Secretary of the United States Treasury, under Alexander Hamilton.

How has British occupation fared in the hands of historians? David Ramsay and the American Revolution’s earliest historians were not always attuned to the ‘ambiguity and compromise that living under military rule entailed’. Ignoring such complexities, they enshrined a simpler story. One with clear sides: evil British oppressors and good American patriots. They found no room for ‘the ambiguities, compromises, and messiness of the revolutionary experience’, which come to the fore when the Revolution is seen through the eyes of those living in its occupied cities.

‘An examination of the everyday lives of those living under military rule’, writes Johnson, ‘reveals that the failure of the British imperial authority in America did not come with the drafting of the Declaration of Independence or the Continental Army’s victory at Yorktown; rather, the failure occurred gradually in the course of the ordinary lives of ordinary people.’ Sceptical readers may not see in that conclusion a disavowal of Adams’s pre-1775 ‘revolution in the minds and hearts of the people’. But, in the ways outlined above, Johnson’s account adds to the richness of a fuller understanding of the American Revolution, a Revolution that remains even more elusive than Johnson lets on. A companion bookend to Adams’s definition is provided by Tillinghast’s teacher, Rush. The American Revolution, maintained Rush, only started with the Peace of Paris in 1783. ‘There is nothing more common’, wrote Rush, ‘than to confound the terms of the American Revolution with those of the late American war. The American war is over; but this is far from being the case with the American revolution. On the contrary, nothing but the first act of the great drama is closed. It remains yet to establish and perfect our new forms of government; and to prepare the principles, morals, and manners of our citizens, for these forms of government, after they are established and brought to perfection.’

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: A view of the City of Boston the capital of New England, in North America Vue de la ville de Boston, capitale de la Nouvelle Angleterre, dans l’Amérique Septentrionale / / drawn on the spot by his excellency, Governor Pownal ; painted by Mr. Pugh ; & engraved by P.C. Canot. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-45584 (b&w film copy neg.) LC-USZ62-31211 (b&w film copy neg. of another copy) LC-USZ62-78014 (b&w film copy neg. of another copy) (Library of Congress, No Known Restrictions on Publication).