In this author interview, we speak to Dr Ian Sanjay Patel about his new book, We’re Here Because You Were There: Immigration and the End of Empire, which explores post-war immigration laws, the afterlives of British imperial citizenship and related attempts to reimagine and rejuvenate British imperialism after 1945. Contributing to transnational histories of decolonisation, the book also explores the interconnections between human rights, post-war migration and international diplomacy.

You can explore further resources on decolonisation in higher education at the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa’s Decolonisation Hub.

Author Interview with Dr Ian Sanjay Patel, author of We’re Here Because You Were There: Immigration and the End of Empire. Verso. 2021.

Q: The title of your book, We’re Here Because You Were There, draws directly from the words of Ambalavaner Sivanandan. How does his phrase open up the themes explored in your study?

Q: The title of your book, We’re Here Because You Were There, draws directly from the words of Ambalavaner Sivanandan. How does his phrase open up the themes explored in your study?

Ambalavaner Sivanandan was a Sri Lankan political essayist and anti-racism campaigner based in London. He was also a gifted aphorist. His phrase ‘we are here because you were there’ captured with a simple elegance the relationship between post-war migrants (we) now settled in Britain (here) on the one hand, and the former crown colonies and other territories of the British empire (there), maintained by Europeans in imperial service (you), on the other.

I use Sivanandan’s aphorism in an expansive way, since my book moves beyond a single relationship between imperial heartland and colony, or home and abroad. Rather, I show that the history of migration and the British empire involved multiple places, groups of people and migrations that interacted in an often overlapping series. Once post-war migration is placed in its various settler-colonial and intra-imperial contexts, you realise that here means more than one destination, there means more than one former home and that you refers as much to previous generations of British white settlers resident outside the British Isles as to a perceived Anglo-Saxon community ‘native’ to Britain.

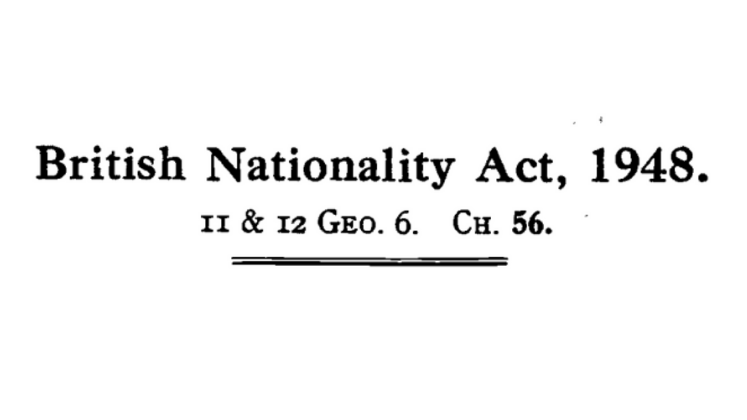

I am also at pains to describe the various legal statuses of post-war migrants to Britain, who were either British citizens (citizens ‘of the United Kingdom and Colonies’) or Commonwealth citizens, both of which groups had unrestricted rights of entry and residence in Britain between 1948 and 1962. (Things become more complicated after this period.) Legally speaking, Sivanandan’s aphorism might have been re-written as ‘we are here under the provisions of British nationality law passed by British lawmakers’ – far more unwieldy and not half as sonorous, I’m sure you’ll agree.

Q: What are some of the key myths that your book challenges when it comes to post-war immigration, Britain’s transition to becoming a post-imperial power and the perceived ‘end of empire’?

Any book on post-war Britain with ‘end of empire’ or ‘after empire’ in its title ought to acknowledge the ambivalences contained within such designations. Although Britain’s formal empire was all but over by the mid-1960s, there was never a final ‘end of empire’ moment in Britain, either at the constitutional level or within the imagination of British political classes. (The announced military retrenchment ‘east of Suez’ in 1968 is sometimes used to mark the final end of empire; I dispute this in the book.)

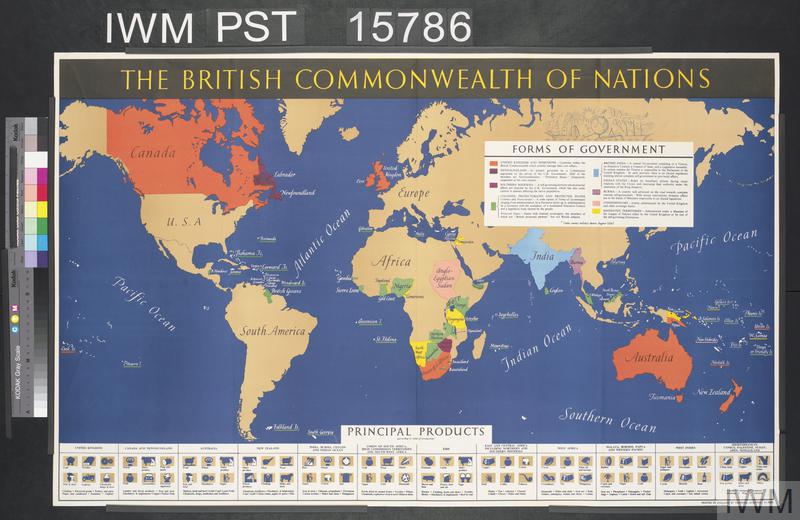

As paradoxical as it might sound, the transfer of sovereign power to former colonies was not perceived as the final end of British imperialism, but simply its latest, evolved iteration in the form of the Commonwealth of Nations. Today, the Commonwealth might hardly seem a formidable vehicle for British imperialism, but its function between 1945 and 1973 was to kick the question of the end of empire into the long grass, as it absorbed the sources of and arguments for British imperial power, both real and imagined, in the post-war decades.

At the level of British nationality and citizenship, decolonisation did not begin in Britain until 1981 and the British Nationality Act of that year. In other words, British nationality and citizenship remained imperial throughout the age of decolonisation and until 1981. The 1948 British Nationality Act created a single, non-national citizenship around the territories of the British Isles and the crown colonies. Once you let go of the intuition that British citizenship must have become national rather than imperial in the 1960s, in line with the end of formal empire, you can begin to understand the paradoxes of post-war Britain. After 1945 Britain was indeed ending formal empire – but not at the level of nationality and citizenship, and not in order to create a post-imperial identity or constitution, but rather to redirect existing and new imperial structures around the Commonwealth. Of course, as it turned out, by the early 1970s even the most quixotic believers in an imperial Commonwealth had to acknowledge it to be more a diplomatic damp squib than a vaunting world-political bloc under British auspices.

Q: Your book stresses the need to move away from seeing post-war immigration as a domestic issue to understanding these diverse international dimensions. What do we gain when we move outwards and encompass international perspectives?

I can well understand why a person’s intuition would be that the story of post-war migration and Britain is confined to the British Isles – after all, a large part of the story is indeed about the circumstances and experiences by which various constituencies of people arrived in Britain itself from former or existing parts of the British empire. But a good deal of the story takes place off-site, overseas, within the memory and practices of colonial governance, and, later, amid the regional and national politics of a new world of postcolonial states.

For example, most accounts of post-war immigration begin with the 1905 Aliens Act passed by the imperial parliament in London. But immigration as we know it today begins somewhat earlier in the white-settler colonies – in today’s Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada. Immigration laws were devised by Anglo-Saxon settlers to protect their colonies from ‘Asiatics’ (Chinese, Japanese, Indians). In other words, migration and immigration laws were occurring intra-imperially, as white emigration from Britain flourished, as indentured labourers were moved from India to the so-called sugar colonies after the abolition of slavery, and Indian immigrants were encouraged to settle in the British East Africa Protectorate. Later, the postcolonial politics of East Africa and South Asia, and Britain’s bilateral relationships with certain key states (among them India and Kenya), would often dictate the exact terms of migration to Britain and immigration policies in the late 1960s. Indeed, one of the more important revelations of the book is the great significance – previously overlooked – of British-Indian relations to post-war migration in the 1960s and early 1970s. These included many diplomatic attempts by British officials to foist British citizens and British Protected Persons – in particular, these were South Asians in East Africa – on to Indira Gandhi’s government for permanent settlement in India. Britain tried – sometimes failing, sometimes succeeding – to exploit India’s complicated relationship after 1947 with so-called overseas Indians, despite the fact that the overseas Indians in question were often British citizens.

Q: You describe the 1948 Nationality Act as a ‘momentous event’. Why is this such a landmark moment for understanding the history of post-war immigration in the UK? Was its significance fully understood at the time?

The 1948 British Nationality Act was momentous because it gave rights of entry and residence in Britain to millions of non-white people around the world, on the basis of their connection to existing crown colonies or independent Commonwealth states. Awareness among British lawmakers at the time of the scale of future non-white migration to Britain appears to have been not far from nil. The true motivations behind the 1948 Act were squarely imperial – namely, retaining and rearticulating the scheme of British subjecthood for the post-war world, and keeping a soon-to-be-republican India in the Commonwealth. The afterlives of the 1948 Act were manifold as the age of decolonisation continued and, yet, successive British governments refused to dismantle the imperial structures of British nationality, instead passing immigration laws as so many bandages on nativist wounds as the imperial heartland became home to more and more non-white migrants.

Q: As a history of post-war immigration, your book also traces state racism in Britain, showing how the UK government introduced racially discriminatory laws that sought to reclassify non-white British citizens as ‘immigrants’. How did non-white immigration come to be constructed as a ‘problem’ in the post-war era and what were some of the consequences for non-white British citizens?

It’s important to understand that a particular kind of hostility after 1945 was reserved for ‘coloured immigrants’, as the term went both among British officials and policymakers and within the national press. The hostility in the 1950s was social, political and administrative – and violent; consider here the 1958 so-called race riots – but in the 1960s and early 1970s this hostility transposed itself into the key immigration laws of the post-war decades. In particular, the 1971 Immigration Act represented a tiering of British citizenship (citizenship of the UK and Colonies) and Commonwealth citizenship along racial lines.

The extent to which British governments were racist in their adoption of post-war immigration laws has occasioned much debate among scholars. The decision to call British citizens (citizens of the UK and Colonies) and Commonwealth citizens ‘immigrants’ – both in the titles affixed to immigration laws and in political discourse more generally – was a rather hulking device by which to fudge any discussion of citizenship rights. Technically, the 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Act and the 1971 Immigration Act are examples of indirect racial discrimination. Yet the effects of the 1968 Act on certain individuals were later found to be an example of racial discrimination and degrading treatment by the European Court of Human Rights in 1973. Most grievously, large numbers of South Asian British citizens resident in Kenya found themselves stateless in reality after the 1968 Act came into effect, despite still being described as British citizens in law. The British attorney general had, however, reassured parliament that because the 1968 Act offered a small number of entry-vouchers to the South Asian British citizens resident in Kenya, it could not be seen as an outright block to their entry, and neither was their citizenship itself being stripped of them.

In the minds of British political elites, non-white immigration was a ‘problem’ that was both abstract and concrete, domestic and international, political and personal, and about both the past and the future. The most prominent claim was that ‘coloured immigration’ led to forms of ‘social unrest’ and social-institutional overstretch in Britain. But no less formative was an associative realm within the minds of British officials in which non-white migrants conjured and embodied the destiny of the empire, the international challenges to Britain’s imperial record and the terms of decolonisation, the stymied imperial ambitions of the Commonwealth and Britain’s embattled place within the international public sphere, and an internal struggle between British imperial idealism and post-war British nativism. Ever implicated in world politics, the racial imagination of British officials and politicians was also interacting with real and perceived forms of transnational black solidarity during the 1960s.

Q: Your book relates how the racially discriminatory nature of British immigration laws attracted widespread international outrage. Did particular voices or institutions lead this international condemnation and how did British officials and politicians navigate the impact on Britain’s reputation on the world stage?

One of my main concerns in the book is to show the ways in which Britain after 1945 was a contender in the making of the post-war world, and that post-war migration was deeply implicated in the vagaries of Britain’s role in world politics after 1945. Decolonisation was not so much a turn inwards to domestic affairs as an adaptation to shifting international realities, norms and values – not least at the level of self-determination, anti-colonialism and racial equality. British political elites’ cultivated self-image was irretrievably damaged by international criticism at the UN General Assembly, in the various diplomatic fora of the Commonwealth, by diplomatic encounters within bilateral relationships and by human rights organisations and bodies such as the International Commission of Jurists and the European Court of Human Rights. This criticism sometimes levelled itself against Britain’s supposedly unique relationship to the rule of law, especially where immigration laws and decolonisation diverged from legal standards. Britain presented itself as an embattled, small island with a crucial ‘world role’ forced to deploy sovereign power in the face of immigration and other forms of crisis. By the late 1960s, Britain’s reputational power, especially at the United Nations, was closer to bankruptcy than apogee.

In other words, post-war British liberal imperialism accommodated the end of direct imperial rule, not as the end of empire, but as the realisation of a particular vision of empire based on constitutional tutelage and constitutional equality within the Commonwealth. Certain British politicians, officials and diplomats used the Commonwealth to reimagine British imperialism for the post-war era and move it towards various kinds of structural power. The Commonwealth was presented as ‘multi-racial’ and thus an answer to the United Nations, yet it was also, and more importantly, a grand constitutional and political receptacle of ‘Anglocentricity’ in world politics – the last vestige of previous imperial dreams of a British-led world government.

Q: Part Three of the book focuses on South Asian migration in the post-war period, particularly the 1968 Kenyan South Asian crisis and the 1972 Ugandan South Asian crisis. How revealing are British governments’ different approaches to these situations at the time?

These often overlooked episodes are deeply revealing ones for post-war Britain, and not simply because two of the great offices of state are currently held by children of East African South Asians (Rishi Sunak and Priti Patel). The South Asians in Kenya facing majoritarian policies in the late 1960s were overwhelmingly British citizens. They held an identical citizenship to Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson himself and an unrestricted legal right of entry to Britain. But such was the resistance to more ‘coloured immigrants’, Wilson’s government passed the 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Act to block their entry, knowing full well it would leave Kenyan South Asian British citizens with ‘the husk of citizenship’, as the home secretary put it in a key Cabinet meeting. This was the first time that an immigration law had been levelled at British citizens per se, and showed the face of British sovereign power at the level of membership, borders and Britishness.

When South Asians in Uganda – a mixture of British citizens, British Protected Persons and Ugandan citizens – were expelled by Ugandan President Idi Amin in 1972, Edward Heath’s Conservative government in the UK balked at reacting in such a way that might be seen to mirror Amin’s act of denationalisation. Instead, Ugandan South Asians with British nationality were carefully cultivated as ‘refugees’, notwithstanding the fact that this was more in spirit than in law. I argue that Britain was here adapting to shifting international values, seeing more international leverage in humanitarian emergency than in the rhetoric of domestic immigration crisis. The new framework was effective in this instance, and many third states offered to settle Ugandan South Asians, including those who were British nationals.

During this same period, and unbeknownst both to the British public and the United Nations, both Wilson’s and Heath’s governments were responsible for the forcible displacement of Chagossians – longstanding inhabitants of the Chagos archipelago – during the preparation of the British Indian Ocean Territory (created in 1965) for US military purposes in the context of the Cold War. Indeed, the forgotten episodes of the end of empire are too numerous to discuss here.

Q: To explore such forgotten and overlooked episodes, what archives did you draw on for your research, and did you face any difficulties in accessing documents and materials?

I drew most heavily on archival material, declassified around the year 2000, from the Commonwealth Office, the Foreign Office and (after 1968) the merged FCO, as well as from the correspondence of those in British diplomatic service. I also draw on a range of other materials – parliamentary records, newspapers and various legal, political and intellectual texts – from a host of countries, particularly in East Africa and South Asia.

There are indeed a range of difficulties in making choices about which documents, materials and archives to use and to seek – and confronting what is and what is not available – not least because each of these is a methodological choice, and relates to one’s ideas about state and society, the domestic and the international, the official and the non-official, time and space, epistemology and evidence, ways of knowing and seeing, knowledge and the politics of knowledge, all amid a myriad of lived realities.

The most intellectually honest metaphor I can think of for the experience of writing a book, or perhaps a first book, is building a plane. I don’t mean this to sound grand or pioneering, but rather improbable and elaborate. You carefully consider your materials, your method of construction, the design of the whole as a dynamic form and the sustainability of its propulsion. Above all, you hope that it might get off the ground when you’re done. When you’re in the middle of the process, the knowledge that you’ll end up airborne is as much about faith as about craft, and in the end no amount of polishing will substitute for the care you took underneath the cladding.

Q: You bring together the lived experiences of non-white British and Commonwealth citizens; of British officials and politicians; and of those associated with new postcolonial states emerging from imperial rule. Did navigating these three sets of experiences pose any challenges when it came to writing the book?

I was keenly aware of the division of labour between these three sets of lived experiences. In a sense, I was trying to control for the fact that as a transdisciplinary writer, I was moving between the legal, the political and the social; as well as between the domestic, international and transnational; and between those who were at the helm of law and sovereign power and those who were not. This sounds very abstract, and in some ways one needs to think conceptually when attempting a global history. I was also interested, conceptually speaking, in demarcating the different kinds of power that the British state attempted to marshal in the post-war period – namely, imperial power, reputational power, structural power and sovereign power. Various British officials, diplomats and politicians overestimated Britain’s remaining imperial and reputational power in the 1960s, yet the sovereign power to determine immigration laws remained with the British state.

But in another sense the various constituencies within the book – at the level of migration and also at the level of state officialdom – were all implicated within the sociology of empire and, later, the sociology of decolonisation. It makes little sense to treat these constituencies as somehow sealed off from one another. Conceptually, too, some of the distinctions I refer to above often make more sense in the abstract than they do within their proper historical texture. South Asians resident in East Africa were African in various ways as much as they were deemed Indian, Pakistani or British in other ways. Equally, the diplomats and politicians active during the age of decolonisation from various countries often knew each other, had studied at the same institutions or had travelled or lived between imperial destinations during the age of empire. The book’s cast of characters is very diverse, including the Indian diplomat, Apa Pant, the political economist, Susan Strange, the sometime adviser on colonial administration, Margery Perham, and the theatre director and migrant from East Africa, Jatinder Verma.

Q: You point out in the book that this history is not widely known. How important is it to recognise the transnational history of post-war migration as ‘not peripheral to post-war British history, but one of its central dimensions’, as you write?

The history of post-war migration in Britain is simply a proxy for and core dimension of an international history of post-war Britain, or perhaps more simply a history of post-war Britain. It is often surprising to me how little understanding there is about the Commonwealth – particularly its imperial and constitutional significance – as well as the actual trajectory of decolonisation, alongside real and imagined forms of post-war British imperialism. Equally, there is little popular understanding of Britain’s settler-colonial history and white emigration, particularly after 1945, and the ways in which these histories directly related to British constitutional structures. The circumstances of post-war migration were dictated by Britain’s self-understanding as an imperial Commonwealth during the first, crucial, post-war decades. The post-war settlement itself, and its upheaval in the 1970s, needs to be conceived within this construction of Britain more generally.

Q: You show that ‘Britain’s transition to a post-imperial age has been subject to endless deferrals’, in part due to a widespread refusal to truly examine – and break – the relationship between immigration, British identity and the imperial past. Do you think that contemporary Britain has the capacity to look ‘within’ and fully reckon with the history explored in your book?

That is a very deep question, one that is implicated in the philosophy of history. History suggests that the most intransigent of things finally change. Britain – if one can refer to state and society in the singular – will be moved into new relationships by the world around it, perhaps more by fait accompli than by choice. Yet one of the strange things that seems to occur when Britain looks ‘within’, as you say, is that as much of its history gets renewed and reimagined in continuity as much as other impressions are finally let go. Historical reckoning is often as disturbing as it is clarifying, not least because some of the imbalances at stake persist. As a social process, historical reckoning is more complex than it might first appear. We are perhaps all of us the less or the more deceived. To speak more plainly, I would suggest that better public education on the history of migration and empire – and empire after 1945 – would be a great place to start. My greatest hope is that the book contributes to this educational redress.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.