In The Public and their Platforms: Public Sociology in an Era of Social Media, Mark Carrigan and Lambros Fatsis explore the discipline of sociology at a time when public life is increasingly shaped by social media platforms. Published in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this timely book argues that contemporary interactions between sociology, publics and social media platforms demand a new understanding of public sociology, writes Rituparna Patgiri.

The Public and their Platforms: Public Sociology in an Era of Social Media. Mark Carrigan and Lambros Fatsis. Bristol University Press. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

The Public and their Platforms: Public Sociology in an Era of Social Media is a timely collection of eight essays that explore the relationship between public sociology and social media. The concept of ‘the public’ has been widely theorised in the social sciences. However, it is also important to understand its relationship with new forms of social media, particularly in the contemporary context. For example, with the emergence of the novel coronavirus globally, almost all educational activities have shifted to online. As such, how do disciplines like sociology adapt to these new circumstances? Mark Carrigan and Lambros Fatsis’ book tries to answer this question.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the social sciences have been under attack from populist and neoliberal regimes worldwide. For instance, in 2015, there was a call to downsize social science and humanities departments in Japan by the education minister in favour of ‘more practical and vocational training’. With the pandemic, this attack has become even more concerted, with questions again being raised about the relevance of the social sciences. As another example, the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) administration in New Delhi has decided to offer Masters-level programmes online in subjects that ‘do not require technical expertise’ in the near future. This decision questions the validity of the social sciences as they are reduced to disciplines that have no ‘technical knowledge and application’.

In this context, Carrigan and Fatsis’ book is a critical intervention. Sociology as a discipline has always been interested in understanding human life and how personal issues become public ones (C. Wright Mills, 1959). In his 2004 presidential address in the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association (ASA), Michael Burawoy gave an institutional term to it – public sociology. It was increasingly felt that sociology should engage with the broader public and contribute towards enhancing the human condition. However, Carrigan and Fatsis argue that it is not enough to just ‘study’ public sociology; it must also be put into practice.

Image by Dean Moriarty from Pixabay

The book begins with the recognition that the concept of public life has vastly changed today – it is now largely online (1). The authors also acknowledge the influence that being part of public spaces has had on the book – public discussions in cafes, bookshops, etc, as well as Twitter discussions and blog posts. The authors argue that the public is not a ‘given’ space but one that is created by interactions between people and their environment (28).

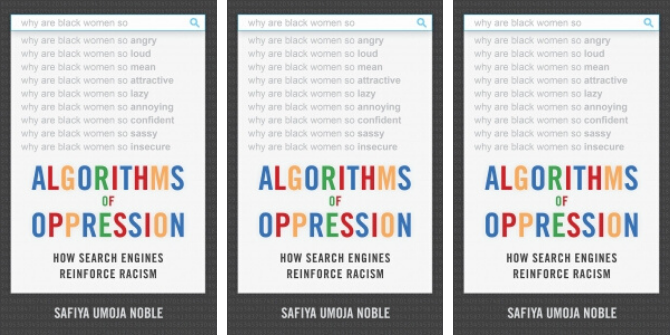

One must also recognise that platforms like social media have become a critical part of how the publicness of disciplines like sociology gets shaped. But platforms like Facebook and YouTube are themselves marred in controversy for manipulating the data of their users. This means that the public is manipulated, multilayered and tangled. Thus, a question can be raised regarding the effectiveness of these platforms for public sociologists to reach out to people as user content is shaped by the platform’s interests. There is uncertainty about who the information would reach and how it will be used (83). There is instant access, but unequal knowledge.

However, one must add here that platforms like blogs and Twitter have definitely helped in connecting academics. For instance, the use of hashtags like ‘soctwitter’, ‘PhDchat’ and ‘academictwitter’ help like-minded people to connect with each other. These online platforms have become ‘sources of knowledge’ and ‘modes of networking’, and even established platforms like journals are recognising this. Many journals nowadays have an Altmetric score for every article, which measures the attention and engagement that each article gets on various sites. Many publishers have also recognised the importance of open access publications. Thus, public sociologists should also take note of the changing notion of the public and how to use these platforms.

The need for a public sociology is particularly heightened by the growing privatisation and marketisation of education. At the same time, it’s also a huge challenge for sociologists to overcome as it is on university premises that most of this public sociology is undertaken. Once again, this is where social media’s role comes in – as it provides an alternative platform that can be skillfully used for disseminating knowledge. Compounded with the COVID-19 crisis, these online platforms have become even more important.

The authors also draw the reader’s attention to the debate between sociology that is considered professional and one that is seen as public in character. Research published in peer-reviewed journals is seen as rigorous academic work (professional sociology), whereas working with communities and social movements is viewed as non-serious, popular, public sociology. Burawoy has critiqued this elitist division (110). Carrigan and Fatsis argue that the online mode and social media have further blurred this distinction.

While there have been many theorisations of public sociology, the authors argue that now is the time to practise it, to ‘do it’. It is critical to break the binary between the activist and the academic, which has plagued public sociology. However, this does not mean that theoretical frameworks and/or conceptual discussions should be abandoned. What, in fact, needs to happen is that these theories and concepts should be executed in practice to improve human life (107).

The authors argue that it is not just that we need a public sociology, but a much humbler public sociology (177). There is a need to see the public as an equal, with a voice as important as that of the sociologists. Thus instead of existing approaches, Carrigan and Fatsis suggest that there is a need for public sociology that challenges the existing hierarchies between sociologists and the public (178). This would be the true essence of public sociology.

In a world in which neoliberal regimes are using social media platforms in innovative ways to reach out to the public, it is critical that sociologists make use of the same to disseminate knowledge. What the authors offer is an alternative understanding of public sociology where the public is much more participatory. This new and alternate sociology in public should emerge from interactions between sociologists, publics and platforms.

However, one concern that I would like to raise is about regional differences. One cannot be certain if the kind of public sociology that works in the Global North would also be effective in the Global South. It is important that we understand the disparities that exist in several parts of the world that different publics face in accessing resources. Recognition and working towards mitigating this inequity should also be a primary focus of sociology in public.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Banner Image Credit: Photo by Shane Rounce on Unsplash.

Proud of you ma’am, interesting to read ❤️

Thanks Anamika!