In The (Un)Governable City: Productive Failure in the Making of Colonial Delhi, 1858-1911, Raghav Kishore explores the transformation of urban governance in Delhi in the nineteenth century, demonstrating that many of the clashes and conflicts in urban planning were ‘productive failures’ that allowed the state to expand its control and the local population to assert their rights and space in urban planning. This is a must-read book for all history enthuasists, writes Gayathri D. Naik, and is also recommended to town planners looking to understand the legacies of this era of planning today.

The (Un)Governable City: Productive Failure in the Making of Colonial Delhi, 1858-1911. Raghav Kishore. Orient BlackSwan. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

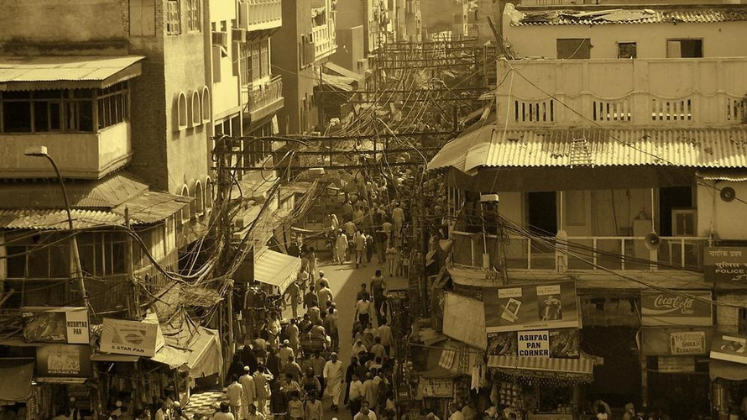

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

The city of Delhi possesses historical strategic and cultural significance, being the centre of power in both the Medieval Mughal era and the majestic Imperial British Raj. It was to Delhi that the revolutionary soldiers from surrounding cities like Meerut marched during the 1857 Revolt to meet and greet their Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar II. Though the revolt ended the Mughal rule, the strategic importance of Delhi never ceased. From 1858, the city witnessed a productive phase until the imperial capital was shifted to Delhi from Calcutta in 1911.

In The (Un)Governable City, Raghav Kishore provides a glimpse of the historic elements of building ‘New Delhi’, exploring the complexity of interactions between different state departments and officials and how their contradictory visions and priorities clashed, leading to conflicts, but at the same time reflecting a ‘productive failure’. Kishore discusses the complexities of planning and enforcement where the planning process was shaped by the varying logics of different planners and the customs and rights of the local population. Through various examples from different sectors, he highlights that many of these failures in implementing developmental planning were fruitful for the state, allowing it to expand its control and the local population to assert their rights and space in urban planning.

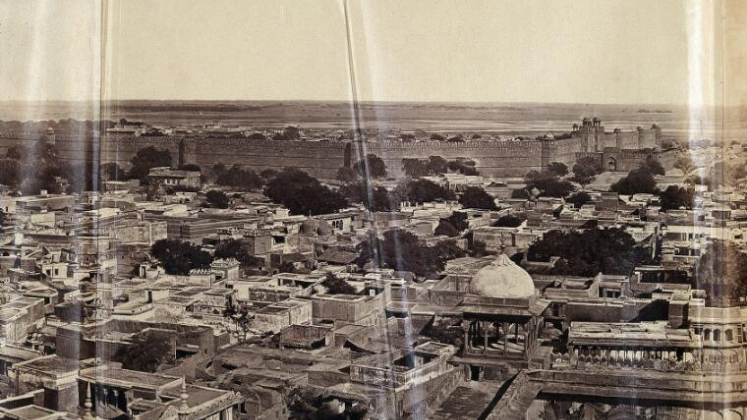

The (Un)Governable City takes the reader through five different scenarios to understand the making of colonial New Delhi. It begins with the aftermath of the 1857 Revolt when the colonial administration took over the city and outlines the challenges it faced. In addition to law-and-order challenges, the civil and military administration of the city faced other troubles, including disciplining the local population and identifying loyal residents.

Image Credit: India: part of a panoramic view of Delhi taken from the Jami Masjid mosque. Photograph by F. Beato, c. 1858. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Though the administration decided to compensate loyal residents during the demolition drive, giving rise to urban markets, this process was not without its faults. Identifying loyalty and addressing the concerns of local elites was tricky. Unwilling to pay the compensation and facing a lack of required properties during the revolt, the government resorted to the market as the primary solution and was left with the need to balance market governance against finding loyal supporters for future city management. Everywhere, complications evolved with conflicts over several plans and the decisions of different departments, including supporters of recognising the customs and rights of the local population.

Given power after 1858 to address sanitation and public order, newly formed municipalities increasingly intervened to improve public health and ‘civilise’ the local population. For this, they tried to differentiate between public and private spaces. In Chapter Two, Kishore highlights that this process, however, was chaotic, inconsistent and irregular. There was inconsistency in understanding local rights and the customs of native residents: for example, the setting up of sabzi mandi (vegetable markets) and the removal of chabutra (the front-raised portions of shops). Kishore also points to the inconsistencies in funding and implementation that caused challenges, but those instances proved helpful in reinforcing and reiterating the power and authority of local governments.

Throughout the book, Kishore stresses the conflicts over decisions and implementations between various departments in municipal governance and urban planning. At the same time, the positive impacts created by such conflicts for the local population in enabling the construction of better amenities and the improvement of local spaces are also emphasised. In all these instances, the self-declared aim of the moral uplift of the colonial state alongside the protection of the local population’s rights and customs was involved.

The attempt to uplift the local population morally and improve their public health also led to interference in their religious activities, such as processions. Discrimination between majorities and minorities when it came to allowing religious activities to be carried out in public spaces created rifts among groups, significantly impacting their age-old customary engagements. An example of Saraogi Processions (a religious procession) by Jains, an influential group in industrial Delhi but a minority in the overall population, explains this context. Such issues of access to the street, as in this example, provided occasions for each religious group to assert their power over new material forms of city life.

While all these instances describe the conflicts between the state authorities and the locals, many planning processes like the construction of the railways in Delhi created contestations between different units of the Imperial government – the Government of India and the Delhi Municipality. However, these failures or contradictions turned out to be positive and productive in building the New City in 1911 by enabling the authorities to build a very planned city, demarcating spaces of new Delhi for the rulers and old Delhi for the locals.

The (Un)Governable City offers a historic narrative that sketches the creation of New Delhi and how the contradictions between and overlapping claims of the Imperial government and municipal authorities created differences between the new city and the old city that continue into today. These planning failures proved productive for the city’s people to assert their claims, and enabled the possibility for sanitation workers, like lower grade sweepers, and local politicians to be corrupt. They often supported law-breaking by locals by either overlooking illegal activities/encroachments or allowing such law-breaking for monetary benefit.

Through various examples, the book provides an account of the unheard history of colonial Delhi, the built-up city that is now the seat of power, and shows contestations among all stakeholders. Kishore argues that planning failures can be recognised as productive failures, considering their contribution to all stakeholders and their role in forming a base for creating a class of noble, elite and loyal subjects of the Imperial Raj.

Nevertheless, in the long term, the question still looms on the horizon: were those failures indeed productive? The planning failures of the Imperial Raj that arose from confusions and differences, the lack of coordinated approach between units of administration, the improper devolution of power, power assertions on one side and the political necessity of creating a loyal class leading to a biased approach to addressing claims and compensations: these all have reverberations in the present-day political economy of the city. As Kishore points out, city planning to create new world-class infrastructure and improve public health and sanitation has been hindered by these historical planning failures, and the unavoidable claims of the population that forms the voter base are a challenge even today. A must-read book for all history enthusiasts, The (Un)Governable City also provides a good read for town planners to understand historic counterproductive faults and failures.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.