In The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company, William Dalrymple gives a new character-driven account of the ascent to power of the East India Company following the collapse of the Mughal Empire and the resulting ‘anarchy’ that followed. Tracking the Company’s ruthless profiteering and territorial conquests, The Anarchy is not only a fine addition to Dalrymple’s studies of the emergence of British rule in India, but also prompts reflection on the dangers of corporate excess in our present, writes Thomas Gidney.

The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. William Dalrymple. Bloomsbury. 2019.

The rapid collapse of the mighty and opulent Mughal Empire in the early eighteenth century stands as almost an enigma of history, but perhaps what was even more improbable was its complete replacement not by a rival state, but by a European trading company a century later. In his latest work The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company, William Dalrymple charts the disintegration of India into a state of civil strife and atomisation, providing a valuable window of entry through which the British sealed their rule over the subcontinent.

The rapid collapse of the mighty and opulent Mughal Empire in the early eighteenth century stands as almost an enigma of history, but perhaps what was even more improbable was its complete replacement not by a rival state, but by a European trading company a century later. In his latest work The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company, William Dalrymple charts the disintegration of India into a state of civil strife and atomisation, providing a valuable window of entry through which the British sealed their rule over the subcontinent.

Much of the research of The Anarchy is built on pre-existing studies of the East India Company and eighteenth-century India, although it is accompanied by an important assortment of manuscripts and Mughal chronicles from Indian and British archives. The Anarchy doesn’t necessarily seek to radically retell the history of the Company or push a new argument or debate; it’s about the way Darlymple recounts the story. He offers a journey through a war-torn and beleaguered eighteenth-century South Asia, focusing on the characters rather than underlying social movements. By concentrating on Mughal nobles, English merchants and Indian financiers, with all their intriguing attributes, Darlymple breathes life into figures from history who, for many of us, are simply names in historical textbooks.

Although some may dispute this character-driven version of events, the attention given to individuals supplies endless nuance and can help in understanding the importance of the social and personal ties that build history. After all, the infamous Battle of Plassey (1757) that marked the way for British dominion in India was not primarily won due to the larger historical currents such as the superiority of European military technology, but because the Nawab of Bengal was betrayed by his ambitious general, Mir Jafar. The instigators of the plot – the Jagat Seths, Marwari-Jain bankers and kingmakers in Bengali politics – reveal the significance of private actors in the rise of the Company. Indeed, the Company itself was not emblematic of a state-driven institution but one responsible to its shareholders. Nor was the East India Company devoid of influence over the British state, as its members used their great wealth to buy positions in Westminster. This emphasis on historic actors effectively breaks down the distinction between state and private agents.

The purpose of the actual ‘anarchy’, the collapse of the Mughal Empire, is largely covered in Chapter One rather than forming a study unto itself, serving to contextualise the rapid ascendency of the East India Company. Although Darlymple recounts the fall of Delhi to the Persian forces of Nader Shah in 1739 with the chagrin of Edward Gibbon’s recounting of the Fall of Rome, The Anarchy’s focus on the rise of the East India Company somewhat skates over the histories of other successor Empires. Though regularly mentioned, the Maratha Empire of the Deccan that arguably instigated the collapse of the Mughals, as well as the short-lived Durrani Empire from Afghanistan that invaded the former Mughal heartlands, are not the focus of this book. Instead they play a supporting role, as both allies and ultimately opponents of the East India Company in its rise to power.

Image Credit: ‘The Surrender of the Two Sons of Tipu Sahib, Sultan of Mysore, to Sir David Baird’, Henry Singleton, circa 1800. Yale Center for British Art, Public Domain courtesy of ArtUK.

When it comes to examining the Mughal’s twilight years however, Dalrymple dives much deeper into the intricate court politics and the tragic figure of one of the last Emperors to make a bid for resurrecting Mughal glory, Shah Alam. A young, intelligent and empathetic leader, Alam’s position as a Mughal Prince granted him considerable gravitas and legitimacy that the Company saw as a possible basis to justify their growing rule in India. Though often little more than a pawn in the clash for supremacy in North India, he was relatively effective as pawns go, almost bringing the Mughals to the cusp of political resuscitation, before being brutally humiliated, robbed and blinded by his former hostage, Mir Quasim. Through these figures of the Mughal Court, Darlymple covers the Mughal Empire’s death throes more forensically than the rise and fall of India’s other Empires.

The real focus of the book, the Company’s ‘relentless rise’, traces the Company from its piratical origins in the Elizabethan period as the birthchild of early monopoly companies that had operated in Turkey and Russia. Despite its less-than-stable origins, the nascent East India Company ran the gauntlet of competitors from Portuguese merchants to the initially more successful Dutch East India Company, before confronting the growing menace of the French ‘Compagnie des Indes’. Only with the anarchy, the collapse of the Mughals and India’s descent into atomisation and civil strife could the East India Company begin its rapid ascent to South Asian hegemony.

The first half of the book begins with the Company’s dominance over Bengal, and its clashes with the local Nawabs for control. This is largely conducted by the figure of the brutish but cunning Robert Clive, whose combined use of subterfuge and aggression won the Company the Mughal right as the ‘Diwani’, or economic comptroller of Bengal. With Bengal, arguably one of the richest regions in the world, under the Company’s control as of 1757, the East India Company gained a dominant position in India. Company officials engaged in a systematic orgy of asset-stripping Bengal, contributing to one of Bengal’s worst famines, killing millions. Rather than organise effective tax or famine relief, as was common among Indian rulers, the Company maintained its tax harvesting to sustain a high share price.

This cold-hearted profiteering is presented as a cautionary tale of the excess of modern-day mega-corporations. However, unlike the less militarised financial institutions of today, the Company’s perfidious actions in Bengal doomed it to evolve into a quasi-governmental organisation. The pillaging of Bengal contributed to the ultimate crash in the Company’s share price, leading to one of the world’s first massive bailout packages in exchange for greater parliamentary scrutiny, which would soon position the UK Parliament and the Company at loggerheads. Edmund Burke’s famous prosecution of the Company’s Governor-General, Warren Hastings – often held up as an admission of guilt by Indian nationalist historians of Britain’s drain of wealth from India – was, Dalrymple argues, aimed at the wrong individual. An intellectual, an Indophile as well as a sharp administrator, Hastings is deemed by Darlymple to have been largely innocent of the many charges levelled against him (though he does not dispute the Company’s general behaviour in Bengal, which occurred often in spite of Hastings).

With Hastings’s removal from office, the Company become a very different organisation, and one run increasingly by military commanders rather than merchants. Backed by Bengal’s tax revenues, the Company, under the control of a redemption-seeking Lord Cornwallis after his failure against American revolutionaries, alongside the Wellesley brothers (including the future Duke of Wellington), embarked on large-scale territorial conquests exceeding those of Napoleon in Europe. Their main opponents, the fractured Marathas and the fearsome Tipu Sultan, reveal the rapidity by which Indian Princes adopted European methods of warfare. Accompanied by a panoply of European mercenaries, Indian armies rapidly closed the technological gap with the British. Yet the financial ability of the East India Company to raise funds for its wars by the end of the eighteenth century allowed it to host much larger armies, often dwarfing the number of troops the British government fielded back in Europe.

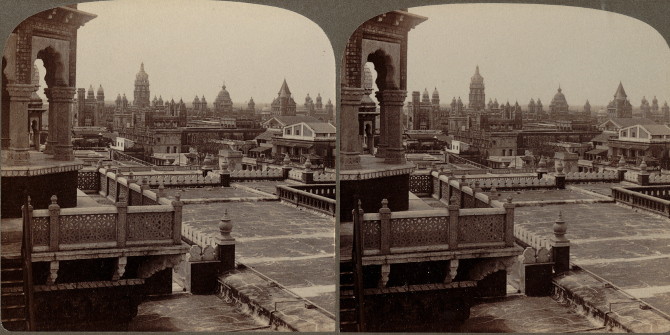

Dalrymple concludes with the fall of Delhi in 1803, when the aging and blind Shah Alam finally comes under the Company’s custody again in a full circle of events. The capture of the Ozymandian city of the Mughals sealed the Company’s hegemony over South Asia, coating their rule with the legitimacy endowed by the Emperor. The choice to finish the book in 1803 rather than with the end of the Marathas in 1818, when the last major South Asian Empire (with the exception of the Sikh Empire in Punjab) had been annexed, accentuates the transfer of power from the Mughals to the British. Although this diminishes the history of other Indian states, it stresses the significance of the retention of Mughal symbols in early British rule, a strange, unbalanced, symbiotic relationship that was simultaneously destroyed half a century later in the Indian revolt of 1857.

The Anarchy is yet another fine addition to Dalrymple’s histories of the rise of British rule in India, setting the scene for his earlier work on the British invasion of Afghanistan (Return of a King, 2012) and the Sepoy Revolt of 1857 and the (re)-capture of Delhi (The Last Mughal, 2006), as well as illustrating the dangers of corporate excess in our present.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

14 Comments