In Harry White and the American Creed: How a Federal Bureaucrat Created the Modern Global Economy (and Failed to Get the Credit), James M. Boughton gives a new account of how US Treasury economist Harry Dexter White came to write the rules for the international economic architecture at Bretton Woods in 1944. This perfectly timed book gives significant insights on the origins of the current economic system and what it might take to build it back better, writes Kevin Gallagher.

Harry White and the American Creed: How a Federal Bureaucrat Created the Modern Global Economy (and Failed to Get the Credit). James M. Boughton. Yale University Press. 2021.

Building back a better system of global economic governance (again)

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

More than a decade after the worst financial crisis of the century, the United States and much of the world is amidst a rash of inequality and right-wing populism, accentuated financial fragility, health and environmental crises, and now war. It is imperative that the global economic system be reformed to deliver stability, prosperity and a lasting peace.

This was essentially the theme of a speech delivered by US Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, this April at the Atlantic Council in Washington DC. Yellen’s speech echoes what her New Deal-era predecessor, Henry Morgenthau, said close to 80 years ago amidst another era of recession, populism, environmental degradation and war.

Morgenthau’s Treasury presided over the 1944 United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. This conference established an international economic architecture that performed fairly well until the 1970s but has become unfit for our contemporary challenges and is one that Yellen is hoping to repurpose for the twenty-first century.

A perfectly timed new book by economic historian James Boughton gives us insights on the origins of the current system and what it might take to build it back better. Historians agree that the US largely gets the credit (or blame) for prevailing over the final design of the post-war international economic institutions of the gold-dollar system of exchange rates, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank). Harry White and the American Creed sheds light on the main architect and negotiator for that system, Harry Dexter White of Boston, Massachusetts.

Image Credit: Photo by Pavel Brodsky on Unsplash

Boughton’s book makes three significant contributions that help round out an otherwise well-trodden story about Bretton Woods and White. First, the book is the first to fully document White’s early life. Second, it traces the evolution of the US Treasury economist and how he came to write the rules for the international economic architecture. Finally, Boughton’s detailed archival research disproves the accusations that White had been a Russian spy throughout his tenure at the Treasury, proving instead that he was one of the many victims of character assassination during the McCarthy era.

White’s parents emigrated from Lithuania to Boston, where Harry was born in 1892. His father opened J Whites Sons Hardware on Hanover Street, now the epicentre of Boston’s North End restaurant culture. Harry worked at the hardware store until serving in World War One in France, after marrying Anne Terry. Anne cared for their two children as White worked around the clock, and she became a well-known author of children’s non-fiction.

White didn’t pursue college until the age of 29, starting at Columbia and finishing at Stanford before attending Harvard for a PhD in economics in 1925 under Frank Taussig. It is here that the seeds of White’s thinking were planted, some of which would become the cornerstones of the economic system for decades. Boughton rounds out the more in-depth analysis of White’s Harvard dissertation provided by Robert Skidelsky. White’s dissertation showed how foreign capital flows from France posed significant risks to its stability and welfare. This laid the groundwork for White’s long-held view that capital flows needed to be regulated to ensure stable exchange rates and full employment.

Upon graduation, White went to the University of Wisconsin as a professor. But when Jacob Viner invited him to work in the US Treasury for a summer, he got the service bug that so many other prominent economists (such as Robert Triffin, Albert Hirschman, Charles Kindleberger and John Kenneth Galbraith) were also called to during this period. Boughton quotes Viner as saying that White was the best government economist of his era. Unlike other economists who eventually left government service to return to academia and advance economic insights based on their practical experience, White was not to live long enough to have that option.

What we learn from Boughton is how White quickly rose through the ranks at the Treasury to become one of Morgenthau’s most trusted advisors. Even though the world was hard at war, Morgenthau tasked White as early as 1941 to write up the plan that would largely prevail at Bretton Woods in establishing the system of fixed but adjustable exchange rates, the IMF and the future World Bank.

Writing up a plan to secure peace while in the midst of war was certainly novel. Yet, as documented by Kindleberger, the US Treasury knew all too well how the failure to reform the system at a 1933 London conference had further globalised the Great Depression and played a role in the rise of authoritarianism and eventual war. Indeed, Boughton argues that it was White who coined the phrase used in so many Morgenthau speeches that ‘prosperity, like peace, is indivisible.’

Boughton’s insight is that Harry didn’t sit in 1941 with a blank page but drew on his experiences dating back to Harvard as well as his previous work at the Treasury. During his first stint in the Treasury, after Roosevelt had recently abandoned the gold standard, White proposed a middle ground to Morgenthau whereby the US dollar would be pegged to gold but countries could adjust their pegs in times of strain. Boughton doesn’t tell us if White was the first or only person to bring this to Morgenthau, but it did form the core of the US proposal at Bretton Woods and ruled the international monetary system until US President Richard Nixon withdrew the peg in 1971.

Boughton is the first to reveal how White’s experience presiding over the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) formed the basis for White’s proposal for the IMF. The ESF was established from the windfall profits accrued to the US after revaluing the gold price in 1934 and was to be used to stabilise the value of the dollar in foreign exchange markets. During his tenure, White expanded the ESF to not only stabilise the dollar in currency markets but also to support foreign countries in paying their dollar-denominated debts in times of stress. White oversaw financing for China, Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil and other countries. This experience formed the basis of White’s plan for the IMF, which, unlike the gold-dollar standard, is about to celebrate its 80th anniversary.

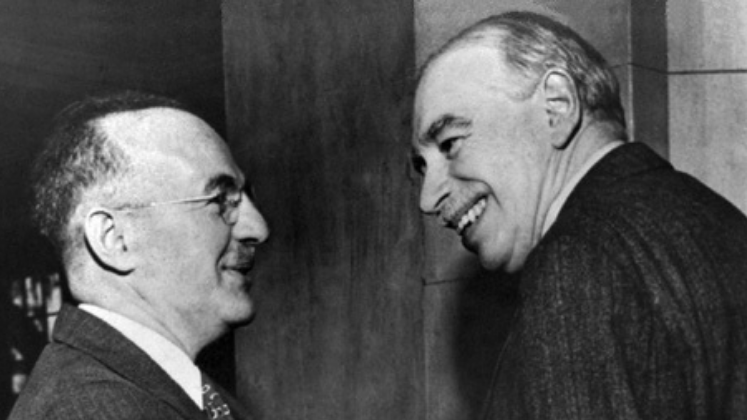

Capital controls — the need to regulate cross-border financial flows to maintain a stable exchange rate, expanding trade and full employment — were enshrined in the making of the IMF. This thinking on White’s end goes back to his dissertation. While John Maynard Keynes also agreed that capital controls should form an essential component of the system, the two disagreed on their nature. White argued that they be used on a temporary basis to weather shocks, while Keynes argued that they should be permanent tools to steer capital toward productive ends at all times. Both Keynes and White agreed that capital should be regulated at ‘both ends’—meaning in both creditor and debtor countries — to ensure stability.

Harry White and the American Creed builds on earlier work by Eric Helleiner that shows how White’s plan for the World Bank didn’t come from scratch either. As White was presiding over the ESF and also working with the US Export Import Bank, he proposed that the US establish a public bank to provide long-term loans at low interest rates alongside the shorter-term loans from the ESF. That proposal was shot down by the US Congress but Boughton shows that this ‘led fairly directly to the successful founding of the World Bank at Bretton Woods in 1944’.

The drama of the actual negotiations has been well documented by Richard Gardner, Skidelsky and others who usually depict them as a grand contest between the great Keynes versus White the lowly bureaucrat. Helleiner adds how White’s earlier relationships with developing countries and the agency of these countries themselves helped lead to some of the final outcomes of the meetings.

By the end of the Bretton Woods negotiations, while Keynes’s plans may have led to a better world economy, White’s plans were only trimmed at the edges. The conference emerged with a fixed but adjustable gold-dollar exchange rate system, an IMF modeled on the ESF and a World Bank modelled after White’s proposal for a development bank in Latin America. Also of vital importance was that to maintain stable exchange rates and trade in the pursuit of full employment, private capital flows were open for stiff regulation.

After the deal was struck at Bretton Woods, Boughton documents how White was able to salvage the core of the agreements despite fierce opposition from the American Bankers Association and the Chamber of Commerce. These actors were not fans of having their international operations regulated and pushed hard against those provisions. Helleiner has shown how White largely prevailed, though bankers forced the final Bretton Woods agreements to water down regulations on capital at ‘both ends’. Moreover, the US later appeased the bankers by allowing participation in the Euromarket which set the seeds for the financialisation of the global economy we witness today.

White did not live to see the glory days of the Bretton Woods institutions up to the 1970s, when there were few episodes of financial stability, where war-torn Europe was rebuilt and unprecedented levels of sustained growth were experienced across much of the world. Boughton documents how White was a workaholic and began suffering heart attacks. Worse, during the McCarthy era, White became the victim of accusations that he was a Russian spy, a narrative that has been perpetuated. Boughton’s deep archival work proves that White was another casualty of the McCarthy-era witch hunts. The stress of work and investigation led to a fatal heart attack and White died in August 1948. Perhaps White would have returned to academia to draw broader insights on the world economy, but he didn’t get the chance.

The world is beginning to look a lot like 1941, and then some. The global system that White helped create, even though augmented by activist Central Banks, failed to prevent and adequately mitigate the global financial crisis of 2008, leading to rising inequality, polarisation, right-wing populism, authoritarianism and war — the very forces that Bretton Woods tried to prevent forever. In addition to needing financial stability for growth and full employment, we are now plagued by pandemics and climate change. Instead of strengthening the global system to deal with these challenges, the US and Western powers turned inward to vaccinate and protect themselves while leaving poorer countries to treat themselves by infection and austerity. Under Donald Trump, the US pulled out of the Paris Climate agreement; while his successor, President Joe Biden, rejoined, he has not been able to muster support for bold initiatives at home and has not provided leadership abroad. And now the US faces war in Ukraine and Cold War-like tensions with China.

Will Janet Yellen be able to construct the right vision for a new Bretton Woods moment and will she be able to deliver? It will take more than one bureaucrat in the US Treasury. It will take leadership in the US and also a recognition that we live in a multi-polar world. White’s criteria for joining the Bretton Woods institutions was signing on the Atlantic Charter, regardless of the economic or political system. In this interconnected world in need of global public goods, carving the world into Cold War blocs of ‘us’ and ‘them’ is not sustainable. We will need to return to White and Keynes’ notions of regulating the financial system and increasing development finance to serve not only full employment, but also a just transformation of the world economy toward a low-carbon, resilient and inclusive one. In the words of White quoted by Boughton, ‘American prosperity and American stability will be built on sand if they are not built on the prosperity and stability of most of the rest of the world.’

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.