In Building on Borrowed Time: Rising Seas and Failing Infrastructure in Semarang, Lukas Ley offers a new ethnography exploring how people in Semarang, Indonesia, deal with the everyday threat of flooding. This fascinating book is worthwhile reading not only for urban studies scholars but for all those wanting to understand the complexity of living in a chronic disaster area from the perspective of inhabitants, writes Adrian Perkasa.

This book review is published by the LSE Southeast Asia blog and LSE Review of Books blog as part of a collaborative series focusing on timely and important social science books from and about Southeast Asia.

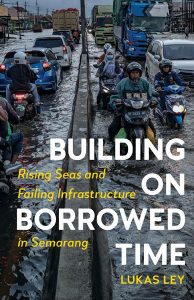

Building on Borrowed Time: Rising Seas and Failing Infrastructure in Semarang. Lukas Ley. University of Minnesota Press. 2022.

There are plenty of works on Indonesian kampung (neighbourhood); however, only a few discuss a kampung where disaster is chronic. In his first monograph, Building on Borrowed Time: Rising Seas and Failing Infrastructure in Semarang, Lukas Ley eloquently describes the kampung Kemijen at Semarang that always faces floods, particularly rob. Rob is a local Javanese term for tidal flooding or tidewater. Tidal flooding has been a threat to Java’s northern shore, particularly in Semarang. It occurs on a constant basis, and the intensity worsens year after year.

There are plenty of works on Indonesian kampung (neighbourhood); however, only a few discuss a kampung where disaster is chronic. In his first monograph, Building on Borrowed Time: Rising Seas and Failing Infrastructure in Semarang, Lukas Ley eloquently describes the kampung Kemijen at Semarang that always faces floods, particularly rob. Rob is a local Javanese term for tidal flooding or tidewater. Tidal flooding has been a threat to Java’s northern shore, particularly in Semarang. It occurs on a constant basis, and the intensity worsens year after year.

Perhaps the reader of this book expects a gloomy or murky illustration of the kampung. On the contrary, Ley offers the sense of local residents’ buoyancy in facing the rob. He employs ‘sinking-in’ observation as a method to study ‘the permutations of the river, infrastructural shifts, and the social experience of flooding’ (27) in Kemijen. As he presents in his book, only the last part contains the feelings of frustration and disappointment for the residents, or at least his main interlocutors.

Ley’s study has five chapters, excluding the introduction and afterword. By using historical documents, colonial maps and secondary literature references, he writes a kind of historiography of the northern wetlands area of Semarang city from the colonial period to more recent times. In the second chapter, Ley attempts to comprehend the influence of political transition and evolving urban ecology on the development of poor neighbourhoods in Semarang’s north via water governance.

In the subsequent chapter, he captures what everyday life looks and feels like in the Northern part of Semarang today. This part has the most pictures compared to other chapters because it contains a photo-ethnographic tour. Chapter Four analyses how government-sponsored citizen participation initiatives change local behaviour and how the actions of organising bottom-up responses to rob affect social order in the kampung. The last chapter, with the title ‘Promise’, shows how the initial optimism of the new polder project at Kemijen, which required local residents’ active participation, slowly faded into disillusionment.

According to Ley, living in the marshy North Semarang has exposed residents to several dangers, including illness outbreaks and periodic floods, since at least the early twentieth century.

Due to the government’s stigmatisation, danger began to develop from inside the kampung over time. Furthermore, danger emanates from the city’s defective infrastructure, which was intended to cure it of its imagined gloomy features. Instead of the government providing a solution, communities and people must organise their own resources in order to respond to an unequally distributed danger, particularly rob.

Image Credit: ‘Polder Tawang’ by jatmika jati licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

The latest solution by the government discussed in this book is the Semarang polder project. Designed by a consortium of Dutch and Indonesian experts, this project was imagined as the beginning of a new era of urban water management in Indonesia. A polder system, in short, is a hydrologically closed system consisting of dikes, dams and water pumps. Following the Netherlands’ polder system, the polder in Indonesia also created a requirement for public involvement, especially local residents. Indeed, the Semarang’s polder in the Banger area established a special water authority called SIMA in 2010. In this authority, local residents and academics were able to play an important role. Unfortunately, this idea is facing failure and only reproducing a cultural imaginary of North Semarang since the Dutch colonial period.

The colonial period according to Ley, is a source of the marginality of the Northern area in Semarang urban development discourses. He argues that colonial urban planning placed the ‘‘swamp particularly low in the hierarchy of liveable places, was strongly associated with a degraded human needing (hygienic) discipline” (51).

Consequently, the colonial government saw urban kampung and its residents as a source of danger, as backward and as lagging behind the trend of human evolution. Two chapters at the book’s beginning elucidate how the colonial power’s spatial hierarchy still has a big influence over contemporary images and ideas of kampung Kemijen and its people. Ley also brings the case of normalisasi sungai (river normalisation) during the 1980s as the epitome of that colonial view.

Looking at another policy of the Indonesian regime during that era, namely Normalisasi Kehidupan Kampus (the normalisation of campus life), Ley argues that river normalisation ‘intended to deter people from settling along rivers that were thought to constitute a realm in which subversive subjects lived and flourished’ (70). The government often condemned the people who settled illegally on the riverbank as a primary cause of floods. Moreover, he draws a linkage between the river normalisation in the 1980s and state modernisation and interventions in the colonial period. He writes that ‘river normalization, a colonial vehicle of modernization, never actually ended’ (88).

On this point, this fascinating book may lend itself to criticism. In fact, there was no river normalisation project at all in Semarang during the colonial period. In Chapter Two, Ley describes how the Indonesian government only initiated river normalisation in 1985. By making a kind of a longue-durée linkage to the colonial past, Ley easily gets trapped into what Frederick Cooper (2005) called looking at history ahistorically, especially by performing leapfrogging legacies. In short, the authors who follow this mode of writing tend to claim that something at time A caused something in time C without considering time B, which lies in between. In this book, Ley says almost nothing about the period after decolonisation and just makes the claim that what happened with the river-related projects is the continuation of the modernisation projects in the colonial period. Perhaps Ley did not have the opportunity to engage with several historiographical works in Indonesian that deal with Semarang in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

Furthermore, another shortcoming of this book is that many Indonesian words or terms have translation errors. Although it is not only intended for Indonesian but general readers, those who understand Indonesian will be disturbed by this issue. For instance, kota bawa (18) means city-bring and is not a translation of the low-lying part of Semarang. It should be kota bawah. Pegal (68) means painful or sore. Perhaps what the author means is begal or robber. Neither the Indonesian nor Javanese word guyung (77) means united. Maybe what the authors means is guyub. Digemas budaya (141) literally means excited about culture. Perhaps what Ley means is dikemas budaya. Another puzzling term is heran saya budaya (182), where I failed to find the proper intention of what the author means.

All in all, the book is worth reading not only for urban studies scholars but also for general readers who want to explore the complexity of living in a chronic disaster area not from the state’s but from the neighbourhood’s perspective.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, the LSE Southeast Asia blog or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.