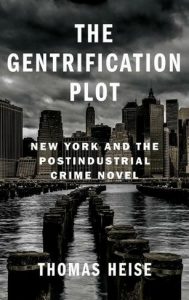

In The Gentrification Plot: New York and the Postindustrial Crime Novel, Thomas Heise investigates gentrification in New York City through the lens of crime fiction. Offering a street-level perspective of the impact of urban renewal projects, this book provides precious insight into contemporary socio-spatial transformations, writes Francesca Cocchiara.

The Gentrification Plot: New York and the Postindustrial Crime Novel. Thomas Heise. Columbia University Press. 2022.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

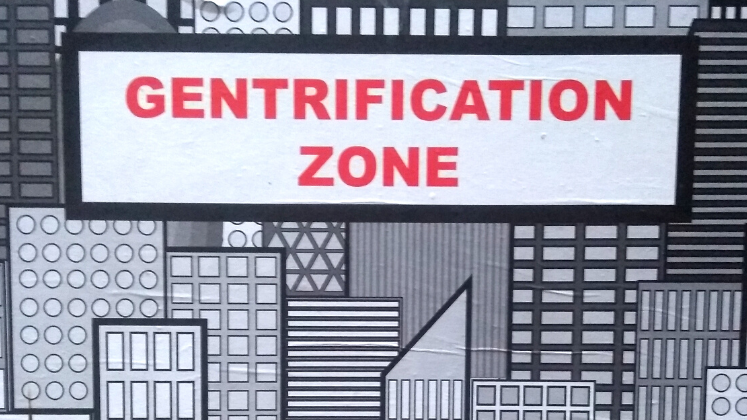

In the last decades, within the transformations of the post-industrial city, gentrification has been a recurrent topic of discussion to the point that, by now, the process is perceived as part of the inevitable fall-and-rise of neighbourhoods. In The Gentrification Plot, Thomas Heise brings in a new perspective by investigating the phenomenon of gentrification in New York City through the lenses of crime novels to trace its true causes. The use of the word ‘plot’ in the title makes a smart hook with literature, using plot as both a parcel of land and a storyline in a novel to suggest that gentrification is itself a story characterised by spaces and events.

One of the advertised benefits of neighbourhood renovation is more efficient management of urban space, especially with regards to safety. In fact, control of crime rates was the banner of the mayoral administrations of Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg between 1990 and the 2010s, leading to the massive re-zoning, demolition and rebuilding of New York. Has this crime crash influenced contemporary New York crime fiction? Heise asks this question because he trusts that literature is a mirror for socio-spatial transformation. Crime fiction takes place in urban environments and unfolds the evolution of the post-industrial city through ever-changing neighbourhoods; the ways this genre has developed might therefore inform us of the issues of the cities we live in.

The Gentrification Plot analyses five iconic New York neighbourhoods through contemporary crime novels that problematise the real process of ongoing gentrification in parts of the city. Most importantly, in these stories, gentrification is the crime. The selected fictions are: Lush Life by Richard Price (set in the Lower East Side); the Jack Yu series by Henry Chang (Chinatown); the Jack Leightner series by Gabriel Cohen, Red Hook by Reggie Nadelson and Visitation Street by Ivy Pochoda (Red Hook); If I Should Die by Grace Edwards and Bodega Dreams and Chango’s Fire by Ernesto Quiñonez (Harlem); and Restoration Heights by Wil Medearis and Bed-Stuy Is Burning by Brian Platzer (Bedford-Stuyvesant).

‘These poor, working-class, African-American, and ethnic neighbourhoods, long associated with high rates of crime, blocks of abandoned buildings, blight, and intractable poverty, have been so fundamentally altered that they are nearly unrecognizable to many’ (10). The Lower East Side, Chinatown, Red Hook, Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant have all witnessed gentrification, profoundly changing the architecture and the demographics of the place. From being isolated, racialised and often redlined districts to becoming prime locations for corporate new developments within the span of a few decades: why should urban makeover in New York be considered a crime? Through his selection of novels, Heise supports the thesis that sparkling, neoliberal urbanism is shadowed by precarious living conditions, displacement and a dramatic sharpening of the existing social gap.

Image Credit: Photo by Laurenz Heymann on Unsplash

The Gentrification Plot not only denounces the current effects of gentrification, a critique that has already been discussed in many Western cities, but it also investigates what led to gentrification in the first place, the causes of pre-gentrification blight and why quality-of-life policing took over as a tool for eradicating urban decay.

First off, Heise aims to deconstruct the perception that gentrification is an inevitable process. Drawing from the reflections of artist Martha Rosler, he argues that ‘When discussing “urban change” we would do well to keep asking basic questions, rather than accepting change as natural or inevitable: who benefits and who does not; whose interests are served and whose are not?’ (28).

Rather than inevitable, Heise contends that the gentrification process is intentional: a systematic attempt for a White, upper-middle-class remake through the infusion of private capital into formerly impoverished neighbourhoods. Just as in crime fiction where the detective traces the precursor events of a crime, the pre-gentrification past of New York neighbourhoods is reviewed throughout the chapters of the book. The outcome of Heise’s investigation is a shifted paradigm: the decline of certain areas was caused by the same logic of economic exploitation that later on would mask itself under the glitter of urban renewal.

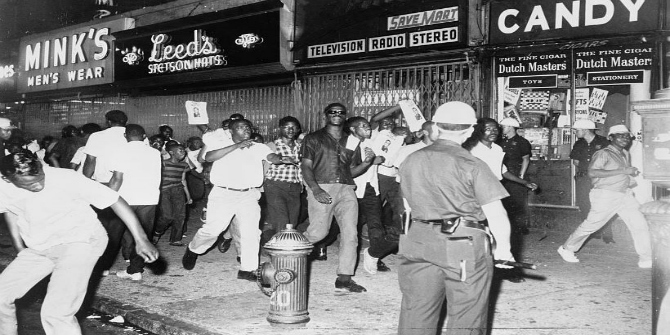

The chapter whose crime stories best illustrate how capitalist urbanism serves to reaffirm White economic power in historically racialised zones is the one dedicated to Harlem. As the poorer and more violent neighbourhood of New York, Harlem is the result of prolonged policies for Black confinement and impoverishment that held it as a frontier for gentrification until the advent of the new millennium.

The neoliberal profiting started to creep into Harlem when its distinctive local culture became a business opportunity to appeal to new visitors. Through governmental programmes and cultural investment funds, cash began boosting mixed-use real estate programmes and culturally-led revitalisations that would attract tourists and treat current residents as customers. Exploiting the local culture for profit-making cleared the way for the later re-zoning of the central and eastern blocks by mayor Bloomberg in 2003. This is the real background of Edwards’s If I Should Die (1997) and Quiñonez’s Bodega Dreams (2000) and Chango’s Fire (2004), the crime novels of this chapter that offer a Black and Latinx perspective on gentrification.

‘These are novels about ordinary people doing anything to make do, including resorting to crime, in a city where every day it is a little harder to make the rent or the mortgage’ (173). The protagonists of these stories try to endorse neoliberal values of self-empowerment and meritocracy as a way to survive, but self-affirmation is an unattainable myth for them. As gentrification shows, whereas social mobility, meaning the choice to resettle and make profit in the city, is paved for the wealthy class, for Black and Latinx people this only translates into forced geographical displacement. In the novels, a sort of fix for these social crimes is found in what Heise calls ‘radical economic self-sufficiency’: smuggling, setting up criminal enterprises and bribing city officials in the desperate attempt to make a living.

In Harlem’s crime stories, detectives wander through urban ruins and visit poor parts of the neighbourhood, revealing the city’s crimes of disinvestment, racial isolation and urban neglect. Heise spotlights the variegated ambience of crime stories to detect the precursors and signifiers of gentrification in Harlem. From decades of redlining policies, vacant plots and building skeletons are juxtaposed with beauty salons, barber shops and locally owned businesses which are threatened by chain stores, new sleek bars and art galleries that will inexorably replace the local culture by homogenising the urban space and making it amenable to outsiders.

You keep burning a neighborhood down, you keep cutting services. With all the unhappiness, crime will rise. Now you can blame the people who live there for the decay of the neighbourhood. The landlords will sit on the burned buildings, vacant lots, waiting it out, because sooner or later the government will have to declare it an empowered zone and throw money their way (210, quoting Chango’s Fire)

Throughout the book, Heise describes how crime novels narrate the many nuances of local culture with its complexity and contradictions. Conversely, gentrification agents are presented in a more impersonal way. The street-level perspective of gentrification through the lens of urban crime stories is certainly a main point of originality in The Gentrification Plot. The book is a very well documented study that contextualises crime fiction in a wider urban discourse by citing the work of researchers and activists who very often are women and members of minorities, breaking the ubiquitous tendency of male authors to only cite other men. Nonetheless, given that crime stories are essentially about the life of ordinary people at the intimate scale of the neighbourhood, it would have been interesting to present examples of crime fictions – if any – that address community efforts that have been able to resist, delay or reverse gentrification, even if these have not been sufficient to block the process as a whole.

The Gentrification Plot is a highly recommended read for those who are fascinated by New York City as a matter of investigation. Readers who loved the meta-detective stories in The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster, or essay collections like The Lonely City by Olivia Laing particularly for the discourse around Manhattan law-and-order policing of the 2000s, will find in The Gentrification Plot new, precious insights about contemporary socio-spatial transformations.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.