In Defensible Space on the Move: Mobilisation in English Housing Policy and Practice, Loretta Lees and Elanor Warwick engage critically with the contentious concept of ‘defensible space,’ first introduced by Oscar Newman in the 1970s, which argued that strategic urban design could be a means of crime prevention. Intervening into this male-dominated discourse, Lees and Warwick examine the journey of ‘defensible space’ from theory to a fixture of residential urban planning in the UK, US and Europe, writes Professor Laura Vaughan.

Defensible Space on the Move: Mobilisation in English Housing Policy and Practice. Loretta Lees and Elanor Warwick. John Wiley & Sons. 2022.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

‘Too many stairs and back door s make thieves and whores’—Sir Balthazar Gerbier, 1663.

s make thieves and whores’—Sir Balthazar Gerbier, 1663.

Hours of fun can be had by urban scholars searching for the origins of the idea that environmental design can improve social problems. Whether it is Hippocrates writing c. 400 BCE how ‘airs, waters, and places’ need to be studied to improve health, or the above-quoted treatise by Gerbier on how architectural design can inhibit the pathways of thieves, clearly there are some accepted paradigms regarding how societies and the places they inhabit interact.

Nevertheless, the lack of evidence for how this interaction works in reality has led to a long seam of research dating back to the earliest social surveys by Charles Booth (1886-1903), who frequently found that introspective places (as H. J. Dyos put it) were seized by the ‘criminal classes,’ whose professional requirements were isolation, an entrance that could be watched, and a back exit kept exclusively for the getaway’. The subsequent years have brought criticism from social scientists, who rail against so-called environmental determinism, with many scholars including Herbert J. Gans continuing to argue today that attributing any agency for architectural or urban settings to shape social outcomes ‘may facilitate architectural thought but it is not a sociological analysis’. This context helps explain how Oscar Newman’s Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design (1972) became one of the most contested concepts in the past 50 years of planning in the UK, North America and Europe, and it is this context that is covered so admirably by Loretta Lees’ and Elanor Warwick’s Defensible Space on the Move: Mobilisation in English Housing Policy and Practice.

Newman’s proposals for designing against crime stemmed from the idea that since people recognise the boundaries of their local environment as a ‘territory’

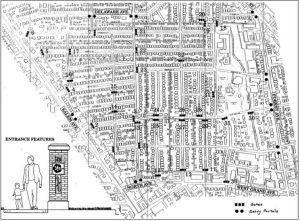

Newman’s proposals for designing against crime stemmed from the idea that since people recognise the boundaries of their local environment as a ‘territory’, they will be able to control their local surroundings if they are clearly demarcated. Segmenting urban residential space into enclosures surrounded by buildings, Newman proposed, would lead to the creation of ‘local communities’, whose internal identity would be strengthened and whose sense of security would improve. Thus, Defensible Space on the Move, which is written by two leading scholars in urban geography and the built environment, analyses the concept in forensic detail, and results in a compelling book. As Warwick points out in the book’s preface, despite valiant attempts to draw clear design guidelines from these ideas (whether well-founded or not), the result of the translation of Newman’s ideas into practice has been ‘confused territoriality, blurred private space and divisive ‘poor doors’ [continuing to be built] into new housing schemes. For such a familiar and easily recognised concept, defensible space is still deeply misunderstood’ (xiv).

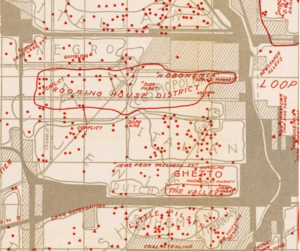

In fact, Lees and Warwick trace the historical roots of Newman’s environmental analysis of crime to the aforementioned Charles Booth on poverty and class in London (which found ‘elements of disorder’ on the city’s back streets), then to Burgess’ model of 1920s Chicago (which located crime in the left-behind areas of the city – see analysis of Chicago’s ‘gangland’ by one of his colleagues in the map below). From there, they track this lineage through analysis which linked poor housing with poverty, and, most importantly, in Jane Jacobs’ influential text which showed that crime tended to be located in the more isolated and less populated sections of social housing, much more than in ‘traditional crowded streets.’

Organised chronologically, Defensible Space on the Move outlines how a theoretical idea made the unusual jump from theory to policy to practice. Describing the many battles with the idea and presenting the arguments dispassionately for and against its interpretation, the book provides a lively account of how practitioners and the popular press grasped on an idea that seemed to be a solution to the widespread problem of social housing in the Western world. Despite the obvious complex interplay of factors that underpin so-called ‘sink estates’ and the authors are among the best qualified to articulate that complexity – it was easy to blame modernist architectural design for the spiral of decline that blighted so much inner-city housing, while proposing architectural approaches to resolving that decline.

Blame is something of a theme in this book. The book describes how planning and architecture researchers responded to Alice Coleman’s book Utopia on Trial (1985), which introduced Newman’s ideas to the UK. Several papers outlining the apparent statistical fallacies in Coleman’s analysis were published by scholars such as Bill Hillier; while Paul Spicker wrote a critique in Housing Studies suggesting that the ‘issues which appear to be problems of planning, design, maintenance or administration are directly attributable to the lack of resources of the tenants.’. This commentary culminated in a conference that same year, Rehumanizing Housing, unusually located outside of academe. Lees and Warwick show how this public discussion of Newman’s ideas helped place housing problems centre stage for expert discussion.

While defensible space ideas permeated modern housing theory, management and social programmes were equally significant in shaping the ultimate success (or otherwise) of housing schemes.

Among several case studies, the chapter on London’s Mozart Estate shows that while defensible space ideas permeated modern housing theory, management and social programmes were equally significant in shaping the ultimate success (or otherwise) of housing schemes. Thus, while architectural determinism is clearly incorrect, the authors show that the contribution of design in shaping the potential for social outcomes is an essential component in the success of planned social housing.

Defensible Space on the Move constitutes an important contribution to feminist scholarship

In closing it is worth mentioning how Defensible Space on the Move constitutes an important contribution to feminist scholarship; providing fascinating insight into the central role played by women in the planning profession – with Alice Coleman, the ‘anti-guru’ – periodically taking centre stage. This makes the book especially timely, given the growing recognition of the need for a female perspective in a variety of fields, and given the recent realisation that the invisibility of women in scientific and medical research, as well as in planning of the public realm, has led to measurable inequalities of outcomes.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Main Image credit: Descriptive map of London poverty, 1889 (north – western sheet) by Charles Booth via the Wellcome Collections on Wikimedia Commons.