In Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict, Sumantra Bose analyses the conflict in Kashmir from its origins to the present, considering the influence of colonial legacies, the rise of Hindu Nationalism and global interventions. Bose makes an urgent, compelling contribution to the understanding of one of South Asia’s most critical political issues, writes Ajit Kumar.

Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict. Sumantra Bose. Yale University Press. 2021.

Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict by Sumantra Bose offers a disquieting analysis of the conflict in Kashmir, and the profound human tragedy it entails. The work is an urgent scholarly intervention at this juncture of Kashmir’s changed political existence. The author attempts to make sense of the political turmoil and shock that dawned upon Kashmiris on the fifth of August 2019, when the erstwhile princely State of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K hereafter) ceased to exist. The present phase of the Kashmir conflict is marked by authoritarian Hindutva onslaughts and the volatile geopolitical upheaval wherein China has transitioned from lurking in the background to occupying a central place in the Kashmir conflict.

Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict by Sumantra Bose offers a disquieting analysis of the conflict in Kashmir, and the profound human tragedy it entails. The work is an urgent scholarly intervention at this juncture of Kashmir’s changed political existence. The author attempts to make sense of the political turmoil and shock that dawned upon Kashmiris on the fifth of August 2019, when the erstwhile princely State of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K hereafter) ceased to exist. The present phase of the Kashmir conflict is marked by authoritarian Hindutva onslaughts and the volatile geopolitical upheaval wherein China has transitioned from lurking in the background to occupying a central place in the Kashmir conflict.

The origins of the Kashmir tragedy lie in the breach of contract by the Indian state and its failure to uphold the proclaimed democratic credentials enshrined in the Constitution.

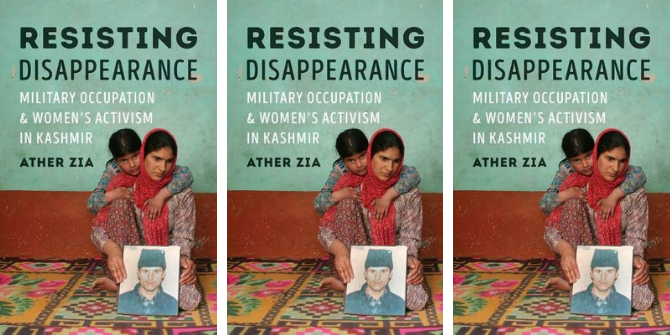

This work’s contribution lies not only in providing a detailed description of the historical context of the conflict, but also in elucidating its contemporary political analysis. The author is among the pioneers of the scholarship on Kashmir, including Chitralekha Zutshi, Mridu Rai, Rekha Chowdhary and Sumit Ganguli. Bose’s scholarship extends beyond historical and political analysis into the human dimension of the conflict by focusing on the individual and community experiences shaped by violence and insecurity. The origins of the Kashmir tragedy lie in the breach of contract by the Indian state and its failure to uphold the proclaimed democratic credentials enshrined in the Constitution. Bose argues that it is this subversion of democratic institutions in J&K by the Indian state which caused the violent insurgency movement. The Indian state employed the repressive apparatus at its disposal by declaring the State of J&K a ‘disturbed area’ or what Giorgio Agamben calls ‘state of exception’. This declaration was followed by the draconian laws such as the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) and Public Safety Act (PSA) as instruments of governmentality to tame the ‘non-obedient’ subjects. Bose explicates the genealogy of the violence that engulfed J&K from the 1990s to 2004, which he claims is a grim reminder of the ruinous potential of extreme nationalism. Such brutal violence, unleashed by the state as well as by non-state actors is the result of competing nationalisms and political subjectivities shaped by conflict.

Such brutal violence […] is the result of competing nationalisms and political subjectivities shaped by conflict.

The first chapter of the book introduces readers to the core of the dispute and its metamorphosis into the protracted violent conflict. The author locates its roots in the British colonial project and the unfinished agenda of partition of the sub-continent. He highlights the authoritarian tendencies of the Indian state as well as of the new Kashmiri political elite headed by Sheikh Abdullah, using examples of how the J&K constituent assembly was elected and the way Sheikh Abdullah was deposed by the Indian state. This undemocratic modus operandi not only resulted in a fraught relationship between the Indian state and J&K, but also led to the contestation between the other regions of the State, namely Jammu and Ladakh.

These claims support the argument that the conflict and violent counter-insurgency response of the Indian state has resulted in a crisis of political legitimacy and ruptured the fabric of society. The protracted violence, apart from taking human lives, has resulted in the perception of the ‘other’ as inimical through the logic of binaries. In this context, Veena Das explains how violence creates differential subjectivities owing to the differential experience of conflict. In a perpetual state of violence, it is difficult to distinguish between resistance and collaboration, oppressed and oppressor.

In a perpetual state of violence, it is difficult to distinguish between resistance and collaboration, oppressed and oppressor.

In the chapter titled ‘Stone Pelters’, Bose expounds the emergence of stone-pelting by Kashmiris against the Indian State forces as an act of symbolic defiance and dangerous catharsis in reaction to oppression. Bose argues that it is the revival of the state of exception regime which brought back the decades-old tradition of mass stone pelting in the valley. The reprisal of stone pelting marked a transition in the mode of Kashmiri resistance, replacing guns with stones as the weapon of protest. However, though one finds a sprinkling discussion about stone pelting as a political act of resistance and the experiences of stone pelters as political actors, the author falls short of exploring the phenomenon in depth. The primary focus of the book is on the Kashmir valley, which overshadows perspectives from other regions in the State (like Jammu and Ladakh), a tendency apparent in much of the scholarship on the Kashmir conflict. This lack of in-depth engagement with regions beyond the Kashmir valley restricts the scope of how the book understands the conflict.

In the chapter, ‘Hindu Nationalist Offensive’, the author meticulously establishes the correlation between the Modi regime’s aggressive Kashmir policy and the Rashtriya Swyamsevak Sangh (RSS) vision on Kashmir. The aim of Modi’s policy, according to the author, is to smother any kind of resistance and political space in Kashmir. In this process, it has blurred the distinction between the so-called mainstream and the secessionists. Despite the attempt, this chapter does not explore thoroughly enough the intricate nature of the right-wing strategies employed in Jammu and Kashmir and crucial factors such as the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which was at the margins of State politics until 2008. Another intriguing puzzle concerns how the BJP has effectively galvanised the political Hindu identity in Jammu. In the case of Article 370; the BJP has invoked Dalit discrimination as a moral argument to justify its decision. This warrants a serious academic examination to comprehend the underlying dynamics of identity politics beyond the Kashmiri framework.

Bose retains some optimism through his blueprint of peace – proposed in his 2005 work, Kashmir: Roots of Conflict and Paths to Peace – modelled on conflict resolution in Northern Ireland.

The author is pessimistic regarding an immediate solution to the violent situation in Kashmir, given the current Hindutva regime. However, Bose retains some optimism through his blueprint of peace – proposed in his 2005 work, Kashmir: Roots of Conflict and Paths to Peace – modelled on conflict resolution in Northern Ireland. He dismisses the idea of a simplistic solution to the Kashmir problem owing to the complex ethnic and regional diversity – what he calls a ‘Matryoshka doll’ which could result in Kashmir facing the fate of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Overall, Kashmir at the Crossroads is a thought-provoking and comprehensive analysis of the Kashmir conflict and provides valuable insights into one of the most important political issues in South Asia. The work could catalyse a dialogue among scholars and policymakers working on the Kashmir conflict in this changed political scenario. Bose makes a case for accommodating the diverse political aspirations of the people of J&K which requires an urgent engagement with the political aspirations of the other regions of the erstwhile State as well.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Main Image Credit: Tasnim News Agency.

Very insightful.

One of the best reviews of the book “Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict” that I came across, worth a read.