Anne Lister of Shibden Hall, Yorkshire has garnered interest over the past several decades, reaching vast audiences through the 2019 TV drama series about her life, Gentleman Jack. A highly educated landowner and businesswoman and intrepid traveller, Lister is best known for her diaries, which run to about five million words. Sections of the diary written in a secret code, cracked 50 years after her death, detail her intimate relationships with women, which led to her being dubbed “the first modern lesbian”.

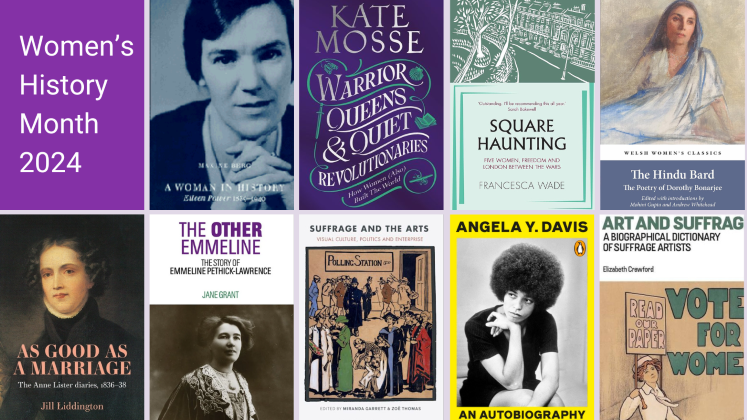

In this interview with Anna D’Alton (LSE Review of Books), historian Jill Liddington speaks about her latest book, As Good as a Marriage: The Anne Lister Diaries 1836-38, an annotated selection from Lister’s diaries which provides fascinating insight into her relationship with (or “marriage” to) local heiress Ann Walker and her working life.

Jill Liddington will give a talk at LSE, Was Anne Lister a pioneer feminist or ‘at heart nothing but an old Tory squire’? on Wednesday 20 March from 6.00 to 8.00 pm. Find details and register here.

Q: Who was Anne Lister and why do her diaries provide such remarkable evidence for feminist and lesbian history?

Q: Who was Anne Lister and why do her diaries provide such remarkable evidence for feminist and lesbian history?

Anne Lister was born in 1791 and lived in and inherited Shibden Hall outside Halifax in West Yorkshire. From when she was a teenager, she started to write a diary, and the more confident she grew in herself and the more powerful she grew, particularly after she inherited Shibden Hall on the death of her uncle in 1826, she wrote more and more. The diary is extraordinary in that it is

estimated now to be five million words, of which a sixth is in a secret code she devised to describe the more intimate details of her life. It is this combination of romantic and sexual intimacy, entrepreneurial activity and intellectual breadth that makes the diaries so magnificent. In 2011, UNESCO added them to its Memory of the World Register.

It is [the] combination of romantic and sexual intimacy, entrepreneurial activity and intellectual breadth that makes the diaries so magnificent.

Q: When was the diaries’ code (describing the more intimate details of her sexuality and relationships) cracked?

Lister, who was a great traveller, died in 1840 in Russia, and the diaries were packed away behind secret panels at Shibden Hall. Ann Walker, Anne Lister’s “wife” (they had an unofficial lesbian marriage in 1834 and lived together thereafter) inherited Shibden Hall, and on her death it went to indirect descendants, of whom the most important was John Lister. He was particularly interested in her politics, and between 1887 and 1892 he transcribed great sections of the diaries and had them published in the Halifax Guardian.

While working with a fellow scholar, Arthur Burrell, in about 1892, he succeeded in cracking Anne Lister’s code, though it wasn’t until decades later, after John Lister’s death in 1933, that an account of this was discovered in a letter by Burrell to the Halifax Librarian. He wrote, “The part written in code turned out to be entirely unpublishable. Mr. Lister was distressed, but he refused to take my advice, which was that he should burn all 26 volumes. He was, as you know, an antiquarian, and my suggestion seemed sacrilege, which perhaps it was.” Burrell continued, “The coded passages presented an intimate account of homosexual practices among Miss Lister and her many “friends” […] this ver unsavoury document contained evidence that these friendships were criminal.”

We might wonder what made and Anne Lister’s lesbian relationships criminal. […]The 1885 Laboucher Amendment […] didn’t include women at all, but the words that scholars use, rightly, I think, is cultural silencing.

We might wonder what made and Anne Lister’s lesbian relationships criminal. The historical context is the 1885 Laboucher Amendment which harshened the criminalisation of male homosexual activity. It didn’t include women at all, but the words that scholars use, rightly, I think, is cultural silencing. Even though there was no law against lesbian relationships, they weren’t to be spoken about, which is why we didn’t know about the code being cracked until a few years after John Lister’s death in 1933.

Q: When did the diaries came to public attention, and how did your own fascination with them arise?

In the 1950s, two other scholars, Dr Phyllis Ramsden and Vivien Ingham, started working on the code. By that stage Shibden Hall had been taken over by Halifax Borough Council. Ramsden and Ingham wrote to the town clerk for permission to publish extracts, who agreed on the condition that they be approved by the local authority committee – essentially censoring the content about her lesbian relationships.

Things changed in 1967 because of the Sexual Offenses Act which decriminalised homosexuality. Again, it only pertained to men, but it allowed more lifting of the cultural silence for women. In 1984 the Guardian published a feature called “The 2-million-word Enigma”, (it was thought at that stage that the diaries were just 2 million words) based on an interview with Phyllis Ramsden and historian Dorothy Thompson, both based in Halifax. A local woman, Helena Whitbread then produced a book on the early Anne Lister in 1988, called, I Know My Own Heart, which had quite an impact. The Halifax Antiquarian Society (which John Lister had helped to form) held a day school in 1989 on Lister which I attended. It was the most disputatious day school I have ever attended, and I thought, there’s more to this woman than meets the eye. I went into the Halifax Archives and decided to write a history of the Anne Lister diaries, published in 1994 as Presenting the Past: Anne Lister of Halifax 1791-1840.

Q: Why did you decide to edit selections from her diaries into the volume Female Fortune, published in 1998, which covers 1833 to 1836?

Q: Why did you decide to edit selections from her diaries into the volume Female Fortune, published in 1998, which covers 1833 to 1836?

I did a word count of the diaries using microfilm and found that they were double the initial estimate. I felt the only tactic as a historian was to take three or four samples of this four-million-word document. I looked at the very earliest diaries which Helena Whitbread hadn’t had access to, starting from when Lister was 15 and detailing her first lesbian relationship with Eliza Raine. I then decided to look at 1819 because I was teaching my students about the Peterloo Massacre, and then 1832, because it was the year of the Reform Act.

For Female Fortune, I focused on the 1830s. That period is interesting to me because it’s when Anne Lister is at her most powerful, after inheriting Shibden Hall, living there with Ann Walker. I wanted to look at the 1835 elections, and how she ran her estate.

Q: What persuaded you to go back after 25 years to work on a sequel, As Good as a Marriage: The Anne Lister Diaries 1836-38 (2023)?

Female Fortune received a fair amount of interest, including from the scriptwriter Sally Wainwright, who had grown up locally and was gripped by Anne Lister’s story. At that stage she was a jobbing scriptwriter and couldn’t get backing for a series about this little-known figure, and so both of us had to pursue other projects. Sally went on to become quite well known, and she returned to the idea. This time, when she pitched a series about Anne Lister’s life, the BBC said yes. What followed was Gentlemen Jack Series One which came out in 2019 on BBC One and HBO, introducing Lister to a new cohort of LGBTQ+ fans across the US and beyond.

Q: As Good As A Marriage focuses on the relationship between Anne Lister and Ann Walker as one of its central subjects. What do these writings reveal about their “marriage”?

From 1836, after Anne’s father and aunt died, the couple were on their own, with their servants, at Shibden Hall, and we can see the marriage up close and personal. It was a volatile marriage, as we can sense from the following quotations from the diaries. On Thursday, 17th August 1837, Anne wrote in code:

“Slept in the blue room [ie, didn’t sleep with Ann Walker], my mind seems comfortably made up. Ann has been preparing Crow Nest [her own house] and has wanted to be away from here. [Shibden] for a long time. How lucky I have not to have introduced her to anyone [Anne was a consummate snob, and the fact she hadn’t introduced Ann Walker to anybody was vital] the sooner she goes, the better.”

Later that day: “She must make up her mind to go or stay. She ought to go properly [ie, decisively]. [The doctor] was right, I should have a great deal of trouble with her. Well, I shall suit myself. I can have excuse enough for being off anytime and letting her do her own way. But while she is with me, I must hold the rein tighter.”

When I first transcribed that, the colour drained from my face: you hold a rein tighter with a horse, it isn’t how you talk about your wife. However, the next day, Friday the 18th, Anne writes, again in code: “Slept with A [Ann], good kiss, [orgasm], she saying it did not tire her at all.” And on Saturday 19th: “Slept with Ann, and she lay down naked after washing, and stayed with me, I grubbling [caressing] her.”

How I interpret this shift is the volatility and complexity of this very unorthodox marriage documented in the diary. Anne Lister does use this coercive, harsh language about Ann Walker, but while she thinks and writes these things, she doesn’t do them. She’s often kind to Ann Walker, and vice versa. They look after each other when they fall ill, and there’s a loyalty there.

Q: What new insights do readers gain about Lister’s life as a landlord and entrepreneur from this latest selection from the diaries?

One of the things that saddened and annoyed Ann Walker was that after breakfast, Anne Lister would be off to her estate and business contacts, leaving her (Ann) behind. Increasingly by the late 1830s, Anne Lister was almost more interested in Shibden and the legacy she would her leave in her estate than she was in Ann Walker.

Increasingly by the late 1830s, Anne Lister was almost more interested in Shibden and the legacy she would her leave in her estate than she was in Ann Walker.

Anne Lister spent her days attending to business, seeing her tenants to find out if they had paid their rent and how they voted in the 1837 election. Though the 1832 Act excluded women from voting (and that remained so till 1918), if you were a landowner with enfranchised tenants, you could check how your tenants voted. Anne Lister doorstepped her tenants rigorously, not allowing any of them to deviate from voting blue, (for the Tories later the Conservative Party) and then checking this in the poll book. Almost every one of her 30 enfranchised tenants voted Tory. So, politically, she was very active and far more powerful than one woman with one vote would have been.

She was also a scholar and read very widely, including in science. She was very interested in geology and read everything by leading geologist Charles Lyell. She kept up to date as far as she could, though women weren’t allowed to go to university, let alone to be members of the learned societies. She read engineering books to aid her in developing her coal mines, which were profitable. She had also inherited Northgate House in Halifax which she turned into a hotel and casino – in the 1830s, “casino” meant a social room with music and drinking rather than a place where you would lose your shirt over a game of cards.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

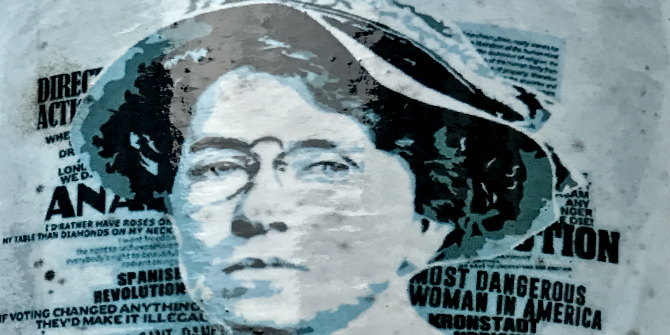

Image credit: Elizabeth O’Sullivan on Shutterstock.