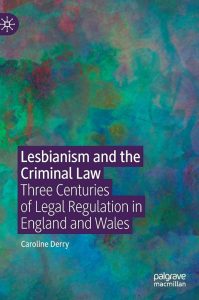

Lesbian relationships in Britain were regulated and silenced for centuries, through the courts and though wider patriarchal structures. In an interview with Anna D’Alton (LSE Review of Books), Caroline Derry speaks about research from her book, Lesbianism and the Criminal Law: Three centuries of regulation in England and Wales (2020) and what the portrayal of same-sex relationships in Agatha Christie’s novels reveals about attitudes towards homosexuality – and specifically lesbianism – in post-war Britain.

Caroline Derry will speak at a hybrid event hosted by LSE Library, Agatha Christie, lesbians, and criminal courts on Thursday 15 February at 6.00 pm.

Q: In your book, Lesbianism and the Criminal Law: Three Centuries of Legal Regulation in England and Wales, you speak of lesbianism being silenced in upper-class British society “because of acute anxieties about female sexual autonomy.” Where did these anxieties stem from?

Q: In your book, Lesbianism and the Criminal Law: Three Centuries of Legal Regulation in England and Wales, you speak of lesbianism being silenced in upper-class British society “because of acute anxieties about female sexual autonomy.” Where did these anxieties stem from?

Women’s autonomy posed a profound threat to patriarchal structures. Marriage, particularly for elite men, was central to maintaining those structures: transfer of property, inheritance, and control over their household all depended upon it. Legally, the wife’s existence was subsumed in her husband’s, giving him power over her property, actions, and sexuality. This was not only true in the 18th century, when the book begins; it persisted through the 19th century and has only slowly been dismantled over the past century and a half. For example, the legal rule that a man could not be convicted of raping his wife was finally abolished in 1991.

There was anxiety that if women ‘discovered’ lesbianism, both individual marriages and the institution itself would be undermined.

There was anxiety that if women “discovered” lesbianism, both individual marriages and the institution itself would be undermined. That was explicitly stated by lawmakers at various points in history. In 1811, Scottish judge Lord Meadowbank said that “the virtues, the comforts, and the freedom of domestic intercourse, mainly depend on the purity of female manners”. In 1921, judge and MP Sir Ernest Wild asserted in Parliament that “it is a well-known fact that any woman who indulges in this vice will have nothing whatever to do with the other sex”. And the 1957 Wolfenden Report, which proposed reform of the law on male homosexuality, spoke of lesbianism as damaging to “the basic unit of society”, marriage.

Q: Why do you write in Lesbianism and the Criminal Law that “Patriarchal oppression […] made the criminalisation of lesbianism almost redundant”?

There were many other ways of regulating women’s lives and relationships that could offer more effective control and less public scandal. These included economic constraints: in the 18th and 19th centuries, married women of all classes had little or no legal control of their own money. Single women without private incomes were little better off. For example, servants’ employers regulated most aspects of their lives under threat of dismissal without a reference.

Social norms set strict limits for unmarried women’s behaviour and gave families a great deal of control over them – although this could sometimes be evaded, as we know from Anne Lister’s diaries! Religious regulation of moral conduct was important, while medicalisation became more significant from the 19th century. Lesbian relationships were pathologised as a symptom of mental illness and the consequences could be awful: an extreme example was the use of clitoridectomy by surgeon Dr Isaac Baker Brown in the 1860s. In the 20th century, “treatments” included aversion therapies and even brain surgery. And until relatively recently, the courts themselves had the power to detain young women in “moral danger”.

Q: Although lesbianism may not have been strictly outlawed, you refer to a “regulation by silencing” of lesbianism within the British court systems. How did this operate?

Legal silencing was based on the assumption that if women – particularly “respectable”, higher class, white, British women – were not told that lesbianism existed, they probably wouldn’t try it. Eighteenth-century models of sexuality assumed women craved men’s greater “heat”, while 19th-century models (which still influence today’s courts) emphasised women’s passivity and lack of independent desire. It was unlikely that two passive and desireless creatures would discover lesbian sex for themselves.

19th-century models (which still influence today’s courts) emphasised women’s passivity and lack of independent desire.

In the criminal courts, silencing worked in several ways. The most obvious was to avoid criminal prosecutions altogether, because court hearings are public and could be reported in the press. So, there has never been a specific offence criminalising sex between women (unlike sex between men, which was wholly illegal until 1967). However, when a prosecution did seem necessary, silencing could be maintained by choosing an offence which concealed the sexual element of the case. There is a long history of prosecutions for fraud where one partner presented as male (cases relevant to both lesbian and transgender history). In the 18th century, this was supposed financial fraud to obtain a “wife’s” possessions; in the later 19th and 20th centuries, making false statements on official documents. And throughout these periods, women have been brought before magistrates for disorderly behaviour and breach of the peace – although few records survive.

Q: What does analysis of the defamation case Woods and Pirie v. Cumming Gordon (1810-1812) reveal about how legal discourses defined morality in relation to race and class?

This Scottish case offers a really potent example of those discourses. A half-Scottish, half-Indian teenager, Jane Cumming, told her grandmother Lady Helen Cumming Gordon that her schoolmistresses were having a sexual relationship. Cumming Gordon urged other families to withdraw their daughters, forcing the school to close, and the teachers brought a defamation claim for their lost livelihood.

The court had to wrestle with difficult questions: could two middle-class women of good character have done what was alleged? If not, how did their accuser come to know of such things? At the initial hearings, the judge’s answer was that the story must been invented by a working-class maid. But when witness evidence was heard, it became apparent that the story originated with Jane Cumming. Attention then shifted to her early life in India. The climate, the supposedly immoral culture, her race, or – in a mixture of race and class discourses – the bad influence of “native’” servants were all blamed.

This supposed contrast between Indian immorality and British, Christian morality was no accident. In the early 19th century, there was a shift in justifications of British imperialism.

This supposed contrast between Indian immorality and British, Christian morality was no accident. In the early 19th century, there was a shift in justifications of British imperialism. Greater awareness of the horrors of violence, corruption and exploitation by the East India Company made it difficult to present their activities as legitimate trading. Instead, a moral justification was claimed: that Indian people needed to be rescued from iniquity by the imposition of superior British law and standards, exemplified by virtuous British womanhood. Many of the judges and witnesses in this case had connections to India, so it is unsurprising that these discourses made a particularly powerful appearance here.

Q: What were the legal implications of the 1957 Wolfenden report for homosexual activity in Britain? What did the report (or its omissions) reveal about attitudes towards women’s sexuality?

The Wolfenden Report recommended partially decriminalising sex between men, but barely acknowledged sex between women. The few mentions implied that lesbianism was “less libidinous” and thus less of a threat to public order. That was important because politically, equality for gay men through full decriminalisation was not attainable at that time. Wolfenden therefore took the pragmatic approach of silencing lesbianism as far as possible, to avoid the question of why women were treated differently by the law, and focusing on arguments specific to male homosexuality. It was successful: Parliament eventually implemented the recommendations in the Sexual Offences Act 1967.

Wolfenden […] took the pragmatic approach of silencing lesbianism as far as possible, to avoid the question of why women were treated differently by the law

Nonetheless, the Report was a watershed event in the legal regulation of lesbianism. Until then, the law had treated male and female sexuality as very different things. Wolfenden introduced the term “homosexuality” into law, and lesbianism became seen as “female homosexuality”. Combined with the Report’s characterisation of lesbians as less sexual than gay men, this meant that lesbianism was treated as a lesser variant of male homosexuality – an attitude that has never gone away.

Q: Was it remarkable that Agatha Christie included or suggested homosexuality in her novels?

Yes and no. These were not issues that were generally discussed in polite conversation. At the same time, lesbian (and gay) people were a fact of life, even if not directly acknowledged. In 1950, most people knew of women living quietly living together like Miss Hinchcliffe and Miss Murgatroyd in A Murder is Announced. Christie walked a careful line in that book, portraying an intimate and deeply loving relationship but showing nothing explicitly sexual about it.

By 1971, when [Christie] wrote of one woman’s love for another in Nemesis, it was no longer possible to directly silence lesbianism in law or society.

And of course, Christie was a rather more daring writer than people often realise: it’s unfair to treat her as a narrowly conservative author of formulaic novels. By 1971, when she wrote of one woman’s love for another in Nemesis, it was no longer possible to directly silence lesbianism in law or society. But Christie was in any event happy to engage with difficult issues in her work, even quite taboo ones like child murderers.

Q: What insights do these portrayals provide into the criminal justice system’s attitudes to lesbianism in post-war England?

Christie’s novels reflect wider middle-class attitudes at the specific times they were written, so they offer insights that we can’t get from court reports alone. They also come from a woman’s perspective rather than that of the elite men who mostly made the law, and gender does make a difference here. Men were convinced that respectable women did not know of such things, but women didn’t necessarily agree!

The novels reveal how the extent to which the courts were keeping pace with wider societal attitudes and understandings.

In particular, the novels reveal how the extent to which the courts were keeping pace with wider societal attitudes and understandings. If we look at medical, psychological and sexological work on women’s same-sex relationships in post-war Britain, the courts seem hopelessly old-fashioned in comparison. But Christie’s books show us that outside expert circles, attitudes were indeed decades behind the latest science. In other words, the courts were reflecting and contributing to mainstream opinions, not falling behind them.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: A still from the the episode, “A Murder is Announced” of the BBC Miss Marple series (1984 to 1992), adapted from Agatha Christie’s novels, featuring Joan Hickson as Miss Marple (left) and Paola Dionisotti as Miss Hinchcliffe (right). This image is reproduced under the “Fair Dealing” exception to UK Copyright law.