Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen and Sámis protest government inaction in light of Fosen court ruling, blocking the entrance to the Oil and Energy Department Image: Terje Bendiksby/NTB via Fritt Ord

Setting the scene

By contextualising the historical plight of indigenous peoples, this article seeks to highlight modern-day perpetuations of subjugation. Utilising the case study of Norway’s government ignoring the Supreme Court’s ruling against the establishment of wind-power plants in Fosen, green colonialism is probed as yet an evolving threat to the Sámi’s existence.

Who are the Sámi?

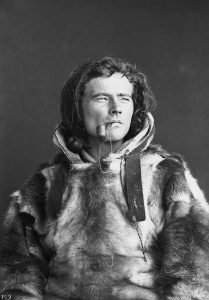

24-year-old Sámi “Josef Henriksen Buljo” photographed in the 1800s: Image: Sophus Tromholt. Distributed via Spesialsamlingene/UIB via NRK

The Sámi are an indigenous people native to Sápmi in their historical homeland of northern Fennoscandia. ‘Sámi’ is merely an umbrella term encompassing many Sámi languages, from northern to southern, and peoples, from coast to mountain. After centuries of hardship and erasure, the Sámi have attained recognition as the national indigenous group by the Norwegian government, political representation in the form of a Sámi parliament, and allocation of resources to revitalise and safeguard their culture and language. Despite the state being responsible for pushing the Sámi to near extinction through its lasting colonial legacies of the 19th and 20th centuries, the current culprit on track to hammer the last nail in the coffin of Southern Sámi existence is green colonialism.

Subjugation and Assimilation

The Sámi’s perceived cultural distinction and inferiority to other inhabitants of Norway was viewed as an obstacle for the newly independent nation-state, finally free from Denmark, in establishing its own national identity. Rooted in the convergence of nation-building’s homogenous ideal, scientific racism, and epistemological violence (Normann 2021, pg. 80), the Sámi people endured an attempted state-led cultural eradication through intensive assimilation policies that formally lasted from the 1850s to the 1960s.

1851 marks the commencement of the state’s approach to Norwegianisation as a political goal, where the “Finn Fund” was established to cleanse Sámi languages from “transitional districts”, where teachers with a successful track record of eradicating their pupils’ native tongue were given a wage increase. Education became a state weapon and schools stood at the frontline in the war.

Sámi pupils with their Nordic teacher, 1941. Image: Lunds universitetsbibliotek via pg 105 “Vettenskapen som försvann?”

Colloquially, the Sámi were referred to as “Finns”, echoing society’s consideration of them as foreign. As such, they were perceived as a security threat, giving Oslo political justification to intensify their Norwegianisation efforts.

Although originally entrenched in politics and culture, the “otherness” of the Sámi would enter a much darker phase of ostracisation. Academia’s fetishisation of racial profiling would manifest itself as scientific racism. Extensive studies of craniology, the exhuming of Sámi burial sites to scrutinise their bone structures, and humiliating nude ethnographic photography were used as tools to explain their inferiority and “primitivity”.

“Picture from Storelvavollen, Brekken 1922. Dr Mjøen from the Winderen Laboratory in Oslo measuring skulls”/ Image: Winderen Laboratorium via Rørosmuseet

“Picture from Storelvavollen, Brekken 1922. Dr Mjøen from the Winderen Laboratory in Oslo measuring skulls”/ Image: Winderen Laboratorium via Rørosmuseet

Their “exoticism” was also showcased in booming and popular anthropological exhibitions, also known as “human zoos”, across Europe and America in the 19th and 20th centuries. Sensationalised by social Darwinism’s grasp on society, the displaying of “primitive peoples” reinforced race as hierarchical, with biological justifications (Lehtola 2014, pg.326).

“Sámis from Kautokeino and Karasjok on display in Paris in 1879”/ Photo: “på ville veger” via NRK

Truth and Reconciliation

The scope of the consequences of these human rights violations can still be felt today in Sápmi. Generational trauma, language extinction, stolen identity, asymmetric health (Truth and Reconciliation Report (TRC), 2023, pg. 364), and emotional and sexual violence display the legacy of a dark past.

To approach the sensitive matter of the enduring consequences of forced assimilation, and to make the necessary efforts for reparations and revitalisation, the Norwegian government established a truth and reconciliation committee. Their report was presented to parliament on 1 June 2023.

Most heart-wrenchingly, the delicately compiled report presents anecdotal evidence displaying first-hand the distressing environment of assimilation-boarding schools that the state heavily invested in. Accounts of Sámi children who, after being ripped from their homes, found themselves in a strange place with an unintelligible language, demystified an obscure part of the nation’s history. The dynamic of these classrooms, plagued by magnified power hierarchies, was said to have been riddled with fear, violence, and shame, tainting the formative years of these children and scarring a generation (TRC, 2023, pg. 276). These institutions proved not only detrimental to the continuation of the Sámi language in Norway: but they also proved damaging to the literacy of many of its pupils, who report having difficulty even to this day with communication and functioning in society (ibid., pg. 227).

The report illuminates the enduring stigma and taboo associated with Sámi identity. It elucidates why many with Sámi ancestry in modern-day Norwegian society choose to conceal it.

Sámi children in a Norwegian assimilation boarding school Image: Sverre A. Børretzen, Aktuell / NTB Scanpix via utdanningsnytt

“Baajh vaeride årrodh!”: a Question of Southern Sámi Survival

A minority group even within the minority Sámi population, only 500 people continue to speak the Southern Sami language. UNESCO has therefore defined it as “severely endangered”, a testament to this people’s particular mistreatment by the authorities.

Inhabiting the southern border of Sápmi, the Sámi reindeer herders would often enter into territorial disputes with the local Norwegian farmers, who would have the backing of not only the state but also a politically charged epistemological fallacy: one such example is Professor Yngvar Nielsen’s thinly postulated “advancement theory”. The theory, based on a three-week observational “study” of place names, claims the Sámi only migrated into Central Norway in the 1700s, putting into question their indigeneity to their ancestral homeland. This theory – which has since been disproved – was cited as late as the 1990s in court cases and land disputes, attesting to academia’s indelible legacy in undermining the Sámi (Hermanstrand et al. 2017, pg.134).

Loud, Ice-throwing, Disrupting Wind Turbines

Given the historical contextualisation of the Sámi’s plight, one would hope the 21st century would prove a secure time for Sámi existence. Although there has been a renaissance of Sámi music and media, catalysed by increased pride and reduced shame, an increasingly climate-conscious world is posing evolving challenges to the Sami.

Motivated by an ambition to achieve a net-zero future, the Norwegian government has spearheaded its investments in wind power, one such venture being the construction of the biggest onshore wind plant in Europe. However, this project, authorised by the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) in 2010, has defiled the indigenous Southern Sámi land in the district of Fosen, jeopardising the future of the already-threatened tradition of reindeer herding in this region.

The Directorate’s decision has raised questions over the transparency of the licensing process for wind turbine plants in Norway, where only recently literature has emerged scrutinising the dominance of heavily centralised stakeholders over local ones (Inderberg et al. 2019, pg. 189). Furthermore, the Plan and Building Act of 2008 entrenched the state’s decision-making power; this has marginalised local municipalities, as well as indigenous and environmental interest groups, in the licensing process (ibid.).

This was exhibited in 2013 when the South-Fosen Sitje and North-Fosen siida’s (Sámi terminology for groups of reindeer herders) appeals against the NVE’s plans for plant construction in their winter-grazing areas were rejected (Ravna, 2022, pg. 158).

Its Implications

Intrinsic to the Sámi culture is reindeer herding, a practice which already threatened by climate change. Near-death experiences of herders, and the sliding of reindeer off steep mountainsides due to slippery “unstable winters” exemplify the practice’s increased hardships in the 21st century (Normann 2020, pg.80). To make matters worse, indigenous land is chosen to develop green energy for society’s needs, adding “insult to the injury” of communities already struggling from the climate change that they were not responsible for (ibid., pg.78).

These projects threaten the tradition of reindeer herding due to increased human activity and destruction of pasturelands (ibid., pg.81), increased stress and less regular grazing by reindeer due to increased sound, and the danger of ice throws from the blades making the herders’ job more difficult and dangerous. The possibility of the cultural continuance of this practice therefore looks bleak.

“Sámi herder in Northern Sweden” Image: Staffan Widstrand / imagebank.sweden.se via Arctic Business Journal

The Fosen case

That was, until on the 11th October 2021 the Supreme Court of Norway ruled the licence for wind power development in Fosen was invalid. Fundamental to the Supreme Court’s decision was Article 27 of the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which states minority people’s right to “enjoy their own culture… should not be denied”. This marked the first time a court ruling has presented a victory for Sámi interests in Norway based on human rights, as opposed to its 1982 decision of siding with hydropower development in Alta, where the fight of the previous generation of Sámi was captured by the 2023 film “Ellos eatnu”. Where the chants were once “La elva leve!”, translating to “let the river live”, the current calls are “Baajh vaeride årrodh!”, meaning “let the mountains live!”.

Despite the court ruling being more than two years ago, the government has ignored the verdict, keeping the wind turbines up. This has spurred protests in Oslo where Sámi activists demand government action.

Sámi protest in front of The Royal Palace Image: Helge Mikalsen / VG via E24

Sámi protest in front of The Royal Palace Image: Helge Mikalsen / VG via E24

A not-so-green, green transition?

The green transition is neither just nor sustainable if it perpetuates the colonial loss of indigenous land and inhibits the reindeer’s crucial role as a carbon retainer in the natural ecosystem.

The notion that the green transition is more important than the preservation of indigenous culture was emphasised by Norway ignoring the UN’s 2018 “calls to suspend the project”. This is consistent with green colonialism, as interpreted by Bjerklund (2022, pg. 8): the amalgamation of resource extraction on indigenous land, the reinforcement of asymmetric power imbalances, and the erosion of indigenous livelihood. He argues that current political associations deny the Sámi “equal and reciprocal terms of cooperation” (ibid., pg. 89), which will eventually lead to the Southern Sámi’s demise.

Moreover, international MNCs have a heavy role in North-Fosen, notably BKW energy and energy infrastructure partners, Swiss companies (which hold 40% of the shares in North-Fosen), and Stadwerke München, (the city of Münich’s public service company, owning 30%). The minority in North-Fosen is owned by domestic Norwegian companies, who have already started negotiations with the Sámi in South-Fosen to remove some wind turbines. The international presence in the vulnerable grazing area of Haraheia in North-Fosen, infringes on the Sámi’s struggle to the supranational, exacerbating the difficulty of removing these wind turbine plants, as both the domestic government inaction and MNCs’ interests are involved. Currently, activists are finding ways to pressure these foreign companies who have managed to survive unscathed from media attention, as opposed to domestic Norwegian companies.

Conclusion

The Fosen case contemporises Norway’s murky past treatment of the Sámi. Embedded in historical power structures that have managed to seep into the 21st century, these events represent yet another example of marginalised communities wielding the brunt of society’s change and suffering disproportionately as a result.

How and where the Norwegian government will grant future licences will be crucial for Sámi survival, but its ignoring of the Supreme Court ruling is no call for optimism. For the green transition to be successful, it needs to be adjacent to indigenous interests and amplify local voices.

By Nicolas Colman

Cover image source: 1928 Lyngen Troms Norway group Mountain Sami people Photo pcard by T. Høegh via Wikipedia Commons (distributed via CC-BY-SA 3.0)