by Zahra Albarazi

#LSERefugees

This paper was presented at a workshop on ‘The Long-term Challenges of Forced Migration: Local and Regional Perspectives from Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq’ organised by the LSE Middle East Centre in June 2016. It was published as part of a collected papers volume available in English and Arabic.

Introduction

Rabia, a Syrian refugee in Lebanon, lives out of wedlock with a man who regularly beats and abuses her. After fleeing Syria, her husband disappeared and her neighbour threatened to hurt her son if she did not move in with him and do as he says. Rabia fell preganant with her abuser’s child and her daughter was born stateless.

Syrian law doesn’t allow her to pass her nationality to her baby, and with no legal link to a father, the baby could not become Syrian. Rabia is also worried about going back to Syria, especially with the many checkpoints that she would have to cross in Lebanon on her way there. Rabia’s daughter is stateless, and therefore Rabia cannot leave.

Rabia’s story is not unique. Statelessness is a challenge and a threat in any country, however, when families and individuals become displaced, the risks and consequences increase substantially. The Syrian refugee context has become protracted and has brought with it a convergence of different factors that make it a perfect platform for statelessness risks and consequences to be heightened. These factors include containing a large population of already stateless refugees, discriminatory nationality laws, complicated personal status regulations of neighbouring countries and state officials extremely sensitive to the two words ‘nationality’ and ‘refugee’. Especially with no clear vision as to what a future ‘Syria’ will look like and what a future ‘Syrian national’ will embody, the need to understand and address the risks families like Rabia’s face is paramount. This paper aims to explore in greater detail how the nexus between displacement and statelessness has become problematic among the displaced from Syria, and to look at ways the humanitarian response to the Syria crisis allows better understanding of the problems of statelessness.

The paper will look at three sets of groups within the displaced population: the general refugee population, those at high risk of statelessness and the stateless refugees.

The General Refugee Population

The majority of refugees, including children born in exile, hold Syrian nationality, and the risk of statelessness is non-existent or marginal. However, experience from other refugee situations around the world demonstrates how the recognition of nationality for some refugees following protracted displacement and/or for children born in exile can have consequences. An example of this could be the case of Liberia, where there are reports of the government refusing the return of some refugees as they are no longer able to prove their link to the country. The consequences of not protecting this link through documentation can hamper future efforts to realise durable solutions.

As part of the ongoing humanitarian response in Lebanon, it seems this is slowly beginning to be understood. There are many good examples of what is being done to prevent statelessness among the general population – humanitarian organisations are seeing the documentation of the displaced as a priority. Counselling, legal assistance and public awareness campaigns on documentation are rife.

Obstacles to this however remain on several fronts, some of the main being:

- There remains a lack of understanding among some stakeholders and authorities that the documenting of a refugee population plays no role in the eventual naturalisation of that population in the host country. Lebanon has a very sensitive view towards naturalisation, however it is yet to be made clear that documenting the population does exactly the opposite – it confirms their Syrian nationality.

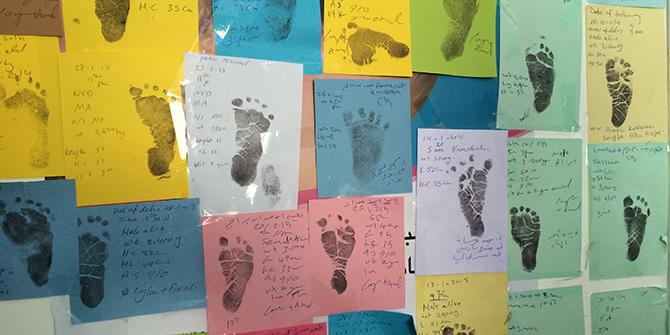

- Public awareness among the displaced population on the civil registration procedures is limited. In Lebanon the procedures differ significantly to those in Syria, and are much more complicated. These procedures become increasingly difficult to navigate when families are in a precarious situation and not prioritising registration of events such as marriages and births. Some processes, such as birth registration, have a temporal deadline which leaves little space for mistakes when families are unaware of the procedures.

- Most importantly, even when individuals are aware of the procedures and have no obstacles accessing them, the most predominant obstacles to accessing the civil registration system are the complexities of the Lebanese infrastructure, mostly prohibitive fees and requirements and the lack of uniformity of regulations across organisations. Registering a birth, for example, involves five steps and each step requires different documents and fees to be paid. If these steps are not completed, then the case will have to be taken to court – often a prohibitively costly and lengthy process …continue reading

Download the paper in English | Download the paper in Arabic

Zahra Albarazi is Senior Researcher at the Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion and a PhD candidate at Tilburg University. She tweets at @zalbarazi.

Other papers in the series

- Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: A Turning Point?

Mireille Girard

- Syrian Refugees and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

Hayder Mustafa Saaid

- Iraqi and Syrian Refugees in Jordan Adjusting to Displacement: Comparing their Expectations towards UNHCR and their Capacities to use their Educational Assets

Géraldine Chatelard

- The Informal Adaptive Mechanisms among Syrian Refugees and Marginalised Host Communities in Lebanon

Nasser Yassin & Jana Chammaa

- Relations Between UNHCR and Arab Governments: Memoranda of Understanding in Lebanon and Jordan

Ghida Frangieh

- The Syrian Humanitarian Disaster: Understanding Perceptions and Aspirations in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey

Dawn Chatty

- The Syrian Refugee Crisis: A Global and Regional Perspective

François Reybet-Degat