by Thomas Fibiger

Compared to other small Arab states in the Gulf, Bahrain has a long history and heritage, documented by a variety of material remains around this small archipelago. Most famous, perhaps, are the burial mounds and temples around the main island, and the layers of city beneath Qalat al-Bahrain, just outside modern Manama, which are associated with the Dilmun and other pre-Islamic civilisations. Excavated and disseminated systematically since the 1950s, this history is key to a national narrative of a long-standing civilisation in Bahrain, important in country’s nation-building during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Apart from burial mounds and other archaeological sites, Bahrain’s topography is marked by significant sites of Islamic history throughout the centuries. Chief among these are old mosques and, as I will focus on here, shrines with the graves of important religious figures. This heritage, however, presents trouble for both the political and scientific regimes tasked with categorising and displaying it. Scientific investigators are unable to archaeologically excavate the graves of famous Muslims who hold spiritual resonance. Political decision-makers face a quandary because much of this heritage is particular to the Shi’a part of Bahrain’s population, and is used to put forward their claim that they used to dominate the islands before the emergence of the Al Khalifa dynasty in the late eighteenth century, and that, thus, Bahrain is ‘really’ a Shi’a country.

If one visits Bahrain National Museum, one will learn nothing about these shrines (although there is a section on Islamic graveyards and tombstones). Furthermore, one will learn nothing about any distinction between Sunni and Shi’a Islam and Muslims, a division which otherwise penetrates Bahrain society, not least in the years following the ill-fated political uprising in 2011. Rather, the National Museum aims to include and represent all Bahrainis, by not addressing religious or ethnic distinctions.

For all the merit such an approach may have, I suggest – based on my interview survey in the National Museum during 2003–5 and subsequent extensive field work among Bahrainis more generally in 2006–18 – that by trying to include everyone, no one really feels represented, and most Bahrainis find their most important heritage better dealt with elsewhere. Inclusion may also be exclusion. So Bahrainis – many of whom are very concerned with their past and heritage – instead focus on their family histories, and their religious and ethnic communities and practices to understand their heritage.

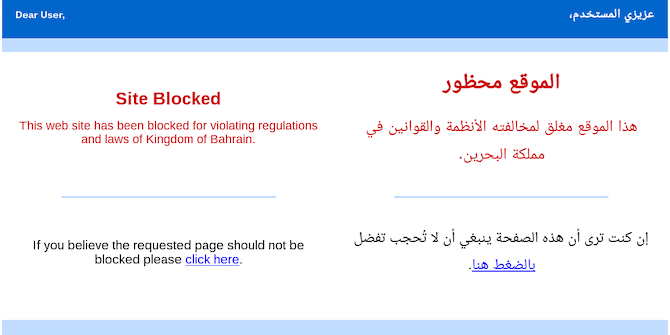

This is not least so for Bahrain’s Shi’a Muslims. While it is not accurate to say that the museum specifically excludes the Shi’a – since the aim is just not to sow any divisions among Bahrainis – the Shi’a find that their particular history and heritage is not included in the national narrative. Thus they see a link between sectarianism and official heritage. An important case in point here is the shrines, which are not appropriated by the museum or any other national heritage body. During my visits to such shrines, I have found a number of people who complain about this. However, the shrines are kept active by the (affluent) Awqaf, or religious endowments, and the related communities, and are probably more well-maintained than if they had been left to a government department.

Some of the shrines date back to the early years of Islam, with some buried saints said to have been companions of Ali. This is the case for Shaykh Sasa’a in Askar (whose shrine was demolished and closed after the counter-revolution in 2011), and the shrine of Shaykh Amir Zayd in Malkiya. Others are well known theologians such as the shrine in Mahooz/Um al Hassam of the thirteenth-century scholar Shaykh Maythem, whose writings inspired Shi’a clerics in the early Safavid empire in Iran.

A third category are the shrines of religious shaykhs who are well known in local Bahraini Shi’a lore, and are thus perhaps the most important to sectarian identity formation – and hence the most difficult to deal with by the political regime and national authorities. The two most famous such shrines are that of Shaykh Abdel Aziz, in the middle of a traffic junction in Sehla, and that of Muhammad Abu Ruman in Dumistan. I have presented the story of Shaykh Abdel Aziz elsewhere, so I end this brief note with the story of Abu Ruman and its, in my mind, complex sectarian coding. This story, apparently, is well known among Bahraini Shi’a today, not least due the shrine of its hero.

At the time of Abu Ruman – a text at the grave says he died AD1178 but the structure of the story could date from any time – Bahrain was ruled by a good and just (that is, non-sectarian) Sunni ruler, but his governor was harsh on the Shi’a. He wanted to convince the ruler that the Shi’a version of Islam was wrong. To that end he planted a pomegranate tree (ruman) in his courtyard and secretly had the names of the first three caliphs inscribed in the tree, as these caliphs are only accepted by the Sunni and not by the Shi’a. As the tree grew big, the names appeared, and the governor called on the ruler to witness this divine sign proving the correctness of the Sunni version of Islam, and the folly of the Shi’a. He insisted that this meant he would need to confront the Shi’a on this revelation.

The ruler did so, but granted the Shi’a leaders three days to come up with a reply to this challenge. One of these leaders was Muhammad Abu Ruman, who withdrew to the desert to pray for God’s help. During the last night a strange man came to him and told him about the trick of the governor. Abu Ruman was told to have one of the pomegranates opened, there would be no fruit it in, only smoke. By revealing this Abu Ruman convinced the ruler of the Shi’a theology’s verity, and their access to divine help. The man who had come to Abu Ruman was said to be Al-Mahdi, the twelfth and last Imam who went into occultation as a small child and is expected to return at the end of days, meanwhile appearing to particular persons in time of severe trouble.

This story, of course, is particularly popular among Shi’a, and can therefore be said to be a sectarian history and heritage. It does however also show that sectarian identities and relations are changeable and negotiable, with a just ruler and a harsh governor, and that co-existence is possible. Even if the particular heritages around Bahrain may be sectarian, they do not have to turn into sectarianism, as an ideology of enmity towards the sectarian other. But if sectarian stories are not acknowledged as ‘true heritage’, then such sectarianism may well be the result.

I have written about shrines, heritage and sectarianism elsewhere, see:

- ‘Global Display – Local Dismay. Debating Globalized Heritage in Bahrain’, History and Anthropology 22:2, pp. 187–202.

- ‘Heritage Erasure and Heritage Transformation. How Heritage is Created by Destruction in Bahrain’, International Journal of Heritage Studies 21:4, pp. 390–404.

- “Sekteriske myter. Lokale diskussioner om historie og sekterisme i Bahrain’, TIFO – Danish Islamic Studies Journal 13:1, pp. 112–133. (in Danish)

This is part of a series emerging from a workshop on ‘Heritage and National Identity Construction in the Gulf’ held at LSE on 5–6 December 2019. Read the introduction here, and see the other pieces below.

In this series:

- Introduction by Courtney Freer

- Souvenir Sovereignty in Qatar by Suzi Mirgani

- Examining Kuwait National Museum by Sundus Alrashid

- Urban Planning and its Legacy in Kuwait by Alexandra Gomes

- Museums as Political Institutions of National Identity Reproduction: Are Gulf States an Exception? by İdil Akıncı

- The New Populist Nationalism in Saudi Arabia: Imagined Utopia by Royal Decree by Madawi Al-Rasheed

- Dubai Expo 2020 and Ancient Mercantile Heritage by Robert Mogielnicki

- Managing UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia: Contribution and Future Directions by Abdulelah Al-Tokhais

- Finding Mariam: the Invisible Woman in National Heritage Mythology by Alanoud Al-Sharekh

- Cultural Attendance: Attracting the Crowds to Museums in Saudi Arabia by Maha al-Senan

- Religion and Heritage in the Gulf: Significant in its Absence? by Courtney Freer

- Historical Archaeology in the Gulf by Robert Carter

- Militarised Nationalism in the Gulf Monarchies: Crafting the Heritage of Tomorrow by Eleonora Ardemagni

- The Practice of Heritage in the Northern United Arab Emirates by Matthew MacLean

- Displaying the Nation in Museum Exhibitions in Qatar by Alexandra Bounia

- Implicit and Explicit Cultural Policies in Qatar: Contemporary Art Production and Censorship by Serena Iervolino

- The UAE State ‘Rebirthing’ of Motherhood: Who is birthing who? by Rima Sabban

1 Comments