by Wafa Alsayed

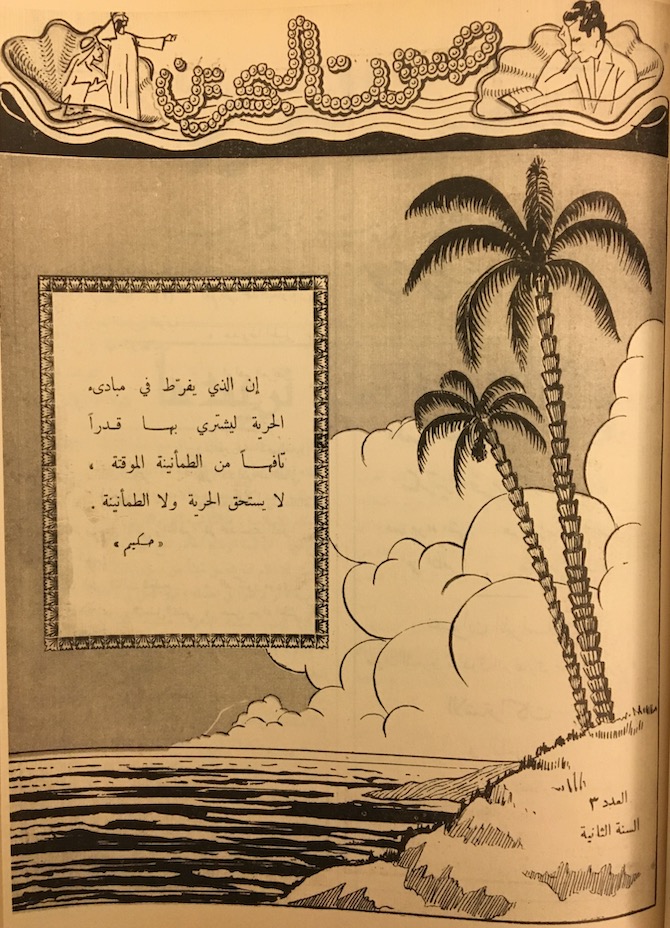

In 1950, a group of Bahraini intellectuals began publishing the magazine Sawt al-Bahrain (‘Voice of Bahrain’). It aimed to promote a modernist, Arab, Islamic and anti-colonial agenda and create a space for the exchange of ideas amongst the nascent intelligentsia. Sawt al-Bahrain was only published for four years, but its impact on Bahrain’s intellectual movement and its connection to the Arab region was critical. It was the first periodical independently run by the intelligentsia, highlighting the 1950s as the decade in which this class emerged as an influential social category. Sawt al-Bahrain offered the intelligentsia a platform to engage with the Arab world, reaching a larger audience by extensively covering Arab issues. The magazine had an impressive geographical reach, which included Gulf cities, Riyadh, Mecca, Medina, Cairo, Iraq, the Levant, Yemen, Tunis, Zanzibar, Karachi and London. The magazine also served as a launching pad for activism, with many of those involved in it playing a leading role in Bahrain’s nationalist reform movement of the 1950s.

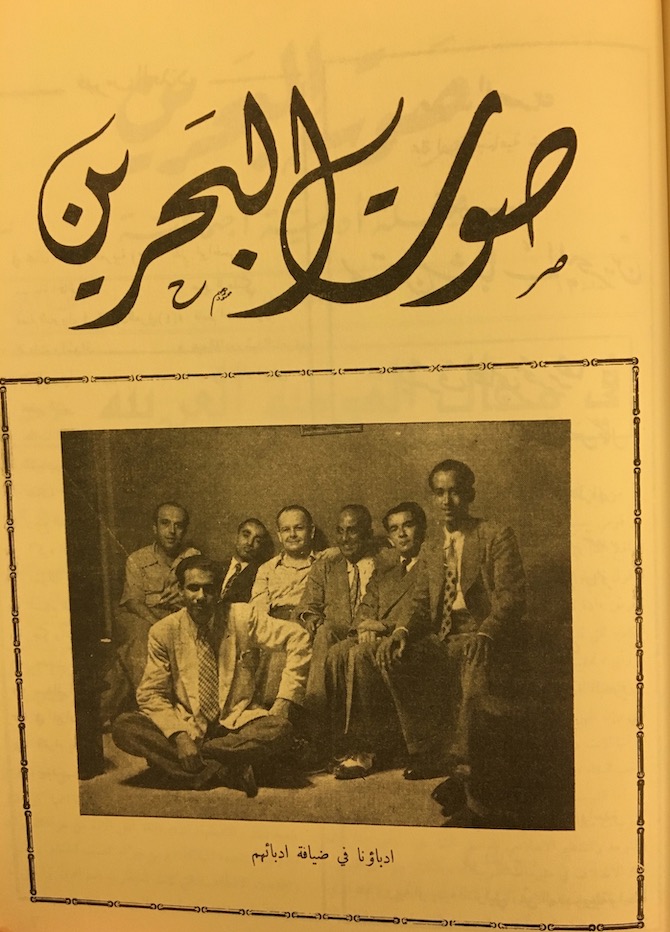

In late 1949, political activist ʿAbd Rahman al-Bakir arranged a meeting with Bahraini intellectuals in which they decided to publish Sawt al-Bahrain. The editors preempted government suppression by appointing James Belgrave, son of the ruler’s British advisor Charles Belgrave, in charge of advertisement and distribution. They also made Ibrahim Hasan Kamal, secretary to the Minister of Education, the editor-in-chief. This helped secure permission to publish the magazine and obtain financial support from the ruler.

Sawt al-Bahrain tackled issues of social justice, economic equality and anti-colonialism. Many of the magazine’s contributors were Bahraini intelligentsia actively involved in politics. The magazine also published articles by Arab writers, especially from the Gulf, where the magazine cultivated a significant readership.

Labour issues featured prominently, reflecting the alliance between the intelligentsia and the workers within the framework of the nationalist movement. Sawt al-Bahrain criticised the treatment of Bahrainis by foreign companies, calling for the right to unionise and better wages and working hours. The foreign-run Bahrain Petroleum Company (BAPCO) became a main target. The magazine also supported workers in Saudi Arabia’s Aramco. Many Bahrainis worked in eastern Saudi Arabia and provided the magazine with information on the labour movement there. The Saudi and Bahraini labour movements were framed as anti-colonial struggles, with a columnist describing the treatment of Saudi workers at Aramco as ‘American colonialism’, which had learned from its ‘master the British state’.

Sawt al-Bahrain advocated for social justice by attacking the still-existing practice of slave owning. In December 1951 Al-Bakir wrote an article entitled ‘Slavery in Islam’ under a pseudonym. In it, he rejected the notion that slavery is permitted in Islam and criticised its existence in the Trucial States and Qatar, calling on those complicit to free their slaves. Additionally, an Omani writer in Karachi wrote an article entitled ‘The Zanj Rebellion and its Impact on Society’, discussing the medieval slave rebellion against the Abbasid Caliphate. According to him, this rebellion was the ‘first social attempt to eradicate slavery and the first revolution by the masses in Islam against the feudal landlords and capitalists’.

Sawt al-Bahrain promoted Arab solidarity while denouncing colonialism. Works by Bahraini authors on Palestine received extensive coverage, such as Ibrahim al-ʿArayyid’s famous epic poem The Land of Martyrs. Following the 1952 Egyptian Revolution, Sawt al-Bahrain exhibited a strong pro-Egyptian line. A poem by the ruling family member Muhammad Ahmad Al Khalifa described Egypt as ‘a sword to be used in the struggle’ and a ‘tribune of Arabism’. Colonial struggles in North Africa were also heavily covered.

The magazine also sought to debunk negative stereotypes about the Gulf states held in the rest of the Arab world. One letter from a reader demanded that the magazine be distributed across the region to expose ignorant misinformation about Bahrain. Bahraini writers also responded to what they considered false reporting in the Arab press. For example, they ridiculed an Egyptian magazine article describing Bahrain as a backwards country whose people do not even speak Arabic. Another writer stated that Sawt al-Bahrain appeared at the right time to counter the negative stances taken by the Arab press ‘at a time when [Arabs] have become more united’.

Sawt al-Bahrain often responded to Iranian claims of sovereignty over Bahrain, which was then under British protection and would not become independent until 1971. One column decried an Iranian parliamentarian’s statement that ‘Bahrain is Iranian’, asserting that ‘Bahrain is Arab’ and Iran cannot ‘repeat the tragedies of Alexandretta and Palestine’ in the Gulf. Another writer affirmed that Bahrain is an ‘integral part of the Arab world’, adding that had Bahrain been under Iranian rule it would have been its right to demand independence. Articles also advocated for replacing the term ‘Persian Gulf’ with ‘Arabian Gulf’ in public and official discourse.

Sawt al-Bahrain’s Arab nationalist rhetoric often excluded and demonised immigrants and those they deemed to be foreign to Bahrain, particularly Iranians. In 1950, Iranians constituted the largest foreign population in Bahrain. This increase in immigration, along with the growing popularity of Arab nationalism and Iran’s sovereignty claims, fed into widespread anti-Iranian sentiments. One article described non-Arab immigration as ‘a critical threat to Arab nationalism’, negatively influencing Bahrain’s ‘language and traditions’. A reader also complained that Iranian-run cafes in Manama display portraits of the Shah. Although Iranians were at the centre of this rhetoric, other nationalities, such as Indians, were also targeted. This contrasted with calls to welcome Arab immigrants to Bahrain. One reader wrote to request that more Arabs be hired instead of foreigners, arguing that the employment of Palestinian refugees would alleviate their plight.

In the early 1950s, sectarian tensions between Shiʿa and Sunnis in Bahrain troubled the intelligentsia, who used Sawt al-Bahrain to disseminate anti-sectarian messages. The magazine published statements in large font such as: ‘Sectarianism is an opening through which colonialism rips apart the unity of the people’. The magazine also tied anti-sectarianism with Arab unity. A Bahraini wrote that ‘colonialism is primarily responsible for hatred and sectarianism’, and the goal of the ‘Arab nation’ should be ‘unity, socialism and independence’.

Women also wrote for Sawt al-Bahrain, including prominent Arab female writers such as the Lebanese Rose Gharib and Palestinian poet Fadwa Tuqan. Bahraini women’s contributions were limited and they often only used their initials or pseudonyms. One female contributor exhorted Bahraini women to ‘revive this paralysed half of society’, adding that women should not be satisfied with teaching or nursing jobs but should become ‘a true partner to man earning her full unqualified rights’. The contributor blamed women’s inability to have their own cultural clubs on ‘[the forces of] abominable reaction’. The magazine published a regular column entitled ‘Madams and Mademoiselles’, which included women’s reflections on topics ranging from childcare and marital relations to education and the freedom to choose husbands. Writers often compared the situation of Bahraini women to that of women in more developed Arab states. One contributor called on women to ‘wake up’ and ‘understand that the Bahraini woman is not different from her cultured [Arab] sister’. An anonymous writer also lamented that Bahraini women are ‘defeated’, while Arab women have ‘come a long way in the field of sophistication’. It should be noted that decades later journalist ʿAli Sayyar admitted that the editor-in-chief, a man, frequently wrote for the women’s column.

While some contributors called for women’s liberation, others rejected these ideas. A male writer addressed a female counterpart who applauded women’s newly found freedoms such as attending the cinema and theatre. He claimed that these activities ‘spoil women’ and that Islam ‘forbade women from leaving their homes.’ This caused a heated debate in following issues. Rose Gharib responded that gender equality is based on ‘the principle that women are human entitled to enjoy the same rights as every other individual,’ and ‘the exclusion of women from society’ has weakened it, subjugating it to colonialism. A Bahraini female writer also criticised the magazine for publishing ‘articles that belittle women,’ adding that nations can only reach a high status through their women.

Though Sawt al-Bahrain ceased publication in 1954, it arguably helped lay the groundwork for the formation of the Higher Executive Committee (HEC) later that year. This opposition organisation brought together Sunni and Shiʿa Bahrainis to demand the establishment of a legislative council, legal reform and the right to unionise. It garnered strong popular support and held strikes and anti-government demonstrations. Many of the founders, editors and regular contributors to Sawt al-Bahrain joined the HEC’s general assembly. Moreover, two of the magazine’s founders, ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Bakir and ʿAbd al-ʿAziz al-Shamlan, emerged as primary leaders of the HEC.

Sawt al-Bahrain is an important resource for research on the Gulf’s social and political history. While scholarship on the region is heavily reliant on colonial archives and Western secondary sources, fewer researchers consult local source material. Gulf periodicals represent a particularly rich body of sources, and many of them have been digitised, republished, or are easily accessible in libraries in the Gulf and abroad, with Sawt al-Bahrain being republished in 2003 by the Sheikh Ebrahim Center. It is time to rediscover these sources and incorporate their narratives into new research on the region.

Hi Wafa, very interesting and important piece!

I have two questions please:

1- Is the archive for Sawt Al-Bahrain available to read online?

2- Do you know who the illustrators were or the team responsible for the graphics in the newspaper?

Thank you, I truly enjoyed reading the article.

Thanks, very interesting

An interesting piece. Could you tell us slightly more about the magazine. Was it weekly, monthy, quarterly? How many articles, how many pages would an issue have? Were the articles from the Arab world outside the Gulf written for the magazine or syndicated/reprinted? Thanks!

Well done an important and informative article. Thank you .

Thank you John for taking the time to read the piece. As for your questions, the magazine was a monthly periodical. Each issue would have around 40 pages. As for the number of articles I would put it at approximately 10-12 (I don’t have the magazines with me at the moment so it’s a rough estimate). In addition to the articles you also have poems and columns that include brief news updates etc. As for the articles from the Arab world, some were indeed reprinted, but not all.