A White Paper on Online Harms is due to be launched by the UK government on Monday, and was leaked to the Guardian yesterday. It will outline the government’s broad plans for social media regulation with the aim of preventing a range of online harms. Here, Impress CEO Jonathan Heawood outlines the many proposals on the table and considers the most likely outcomes.

A White Paper on Online Harms is due to be launched by the UK government on Monday, and was leaked to the Guardian yesterday. It will outline the government’s broad plans for social media regulation with the aim of preventing a range of online harms. Here, Impress CEO Jonathan Heawood outlines the many proposals on the table and considers the most likely outcomes.

Until recently, the idea of ‘regulating the internet’ was something to laugh about, not something to legislate for. Surely, the internet was too big, and too free, to be capable of regulation! Whether you were a net utopian or a pragmatist, you saw things the same way: the internet could not, should not and would not be regulated.

All that has changed. After a decade of losing ground to Silicon Valley, the press last year woke up to the existential threat posed by digital intermediaries. Electoral interference! Hate speech! Data violations! In story after story, they highlighted the harmful impact of social media platforms and search engines.

Last November, the Guardian proclaimed that Facebook ‘is long overdue a regulatory reckoning.’ The Mail has urged the government to ‘stand up to these utterly unscrupulous multinational leviathans.’ The Telegraph is pushing for statutory regulation. The Independent is clear that any new internet regulator should ‘answer directly to the government.’

Despite their economic travails, the press are still capable of framing a powerful narrative, and this barrage of news stories and leader columns had its desired effect. The government last year published a Green Paper on internet regulation, and a more detailed White Paper is now overdue.

However, the delayed publication of the White Paper seems to have sent jitters down Fleet Street. On 24 March, the Mail on Sunday reported on concerns that regulation of social media could introduce ‘press regulation by the back door’. Ian Murray, Director of the Society of Editors, has expressed fears that a new regulator could restrict ‘the public’s right to know’, whilst Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, has cautioned against statutory regulation of social media on press freedom grounds.

It is right to be cautious about any new form of media regulation. However, there is something odd about the present situation. Didn’t the press want social media to be regulated? Or did they really just want the government to get rid of an awkward competitor? Is there a real risk that social media regulation will amount to ‘press regulation by the back door’? Or can we address harms in one part of the media without sending ripples across the entire ecosystem?

There is still no White Paper to answer these questions. But there are many proposals already on the table. Over the last twelve months, parliamentarians, academics and civil society groups have looked in considerable detail at the options for internet regulation. By reviewing the most significant of these proposals, we can start to anticipate what is – and is not – likely to be in the White Paper; and whether this is likely to affect press freedom.

First, we need to understand that these initiatives come from very different places. Some have addressed the same problems as each other in different ways, whilst others have addressed different problems in similar ways. Some are cautious; others are bold. Some address a small issue in great detail whilst others attack the canvas with a broad brush. There is plenty of scope for confusion.

As a result, the Mail seems to believe that the government will create a new regulator – ‘Ofweb’ – that will directly regulate social media content. Nobody has actually proposed anything quite like this, although some groups have recommended the establishment of new public bodies with regulatory responsibilities for aspects of social media.

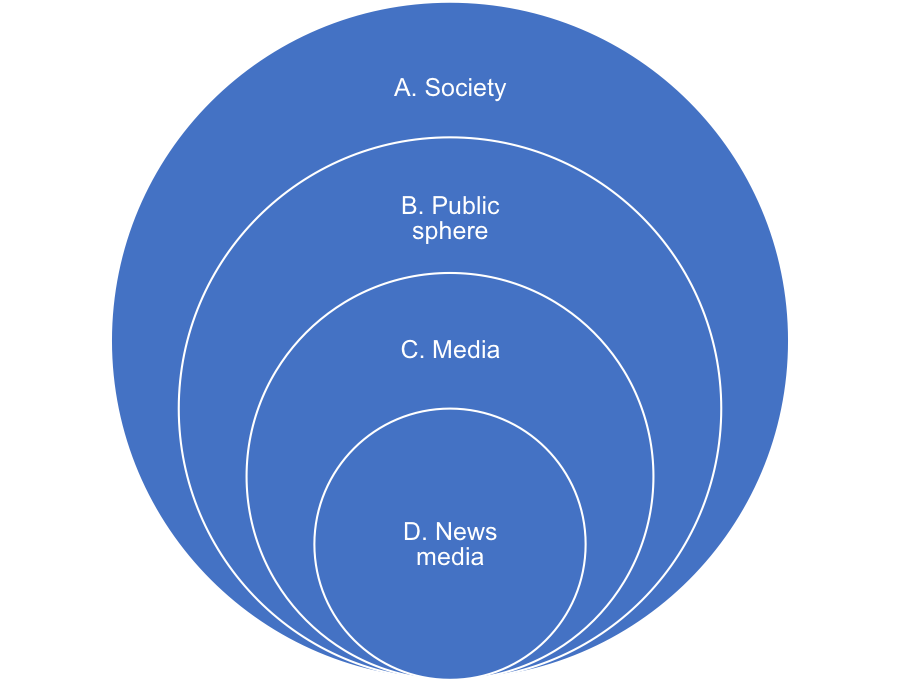

So, before we can make sense of the White Paper, we need to make sense of the proposals that are now on the table. These operate at four levels:

- Some initiatives have set out to address issues that affect society as a whole.

- Others have been looking at the public sphere.

- Some have been looking at the media industry in general.

- And others have been looking at journalism in particular.

Let’s take a quick look at some of the most interesting initiatives on these four levels.

Society

Initiatives at this high level tend to be concerned with issues that affect the economy, public health and wellbeing. They tend to have very little to say about media content or individual expression.

- In September 2018, Professor Jason Furman was appointed by the Government to chair an Expert Panel on Digital Competition (‘the Furman Panel’), which published its final report, ‘Unlocking Digital Competition’, in March 2019. The Panel called for a new ‘Digital Markets Unit’, to keep a weather eye on competition issues emerging from the digital economy, such as monopolisation in the search and social sectors; and vertical integration in the digital advertising market.

- In October 2018, Doteveryone published a report on ‘Regulating for Responsible Technology.‘ The report recommends the creation of a new ‘Office for Responsible Technology’, to inform and coordinate the work of regulators across all sectors, from healthcare to legal services. This body would not be a content regulator of first resort. However, it would provide ‘backstop mediation’ for disputes that could not otherwise be resolved, including disputes about social media content.

- In March 2019, the New Economics Foundation (NEF) published a report, ‘Digital Self-Control: Algorithms, Accountability and our Digital Selves’. This report calls for greater transparency about the impact of algorithms on all aspects of our lives, and a new ‘digital passport’ and ‘national data store’, to help individual citizens control their personal data. It does not specify a regulator (old or new) to oversee this regime.

- In 2018, the Carnegie UK Trust launched a programme of work, led by Will Perrin and Lorna Woods, on harm reduction in social media, which resulted in the publication of a report, ‘Internet Harm Reduction’, in January 2019. Perrin and Woods recommend that Ofcom should be empowered to uphold a ‘duty of care’ on social media and messaging platforms, to mitigate any harmful impacts of their actions. They propose that platforms should be free to define harms according to their own standards, subject to some ‘heads of harms’, to be set out in statute. This proposal has attracted considerable interest from policymakers and is likely to be reflected in the White Paper. Whilst it may bite on freedom of expression and press freedom – to the extent that platforms carry news content – this proposal would in effect merely require platforms to set appropriate terms and conditions; but that their enforcement of these terms and conditions would be overseen by a statutory body. This is far removed from the direct content regulation that Ofcom currently practises in relation to broadcasters, for example.

Public Sphere

These initiatives tend to be concerned with issues that affect elections, political communications and advertising.

- In June 2018, the European Council called for a coordinated European response to the challenge of disinformation. In response, the European Commission published an Action Plan on Disinformation in December 2018. The Action Plan calls on digital intermediaries to act on a voluntary basis to remove disinformation from platforms and search engines. It threatens regulation in the event that intermediaries do not take sufficient action.

- In September 2018, the major digital intermediaries and advertisers published a ‘Code of Practice on Disinformation’, in response to pressure from European policymakers (see above). This is a self-regulatory response of the simplest kind. It describes a range of voluntary actions that intermediaries are taking, but does not set out any mechanism for oversight or accountability.

- In January 2017, the House of Commons Select Committee on Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (‘the Commons Committee’) launched an inquiry into fake news. The Committee published its final report, ‘Disinformation and “Fake News”’, in March 2019. The report recommends the creation of a new regulator to uphold a statutory code of ethics for tech companies, and that ‘proven sources of disinformation’ should be removed. The Committee is keen to stress that any such measures should be balanced against the need for freedom of expression and press freedom, but there are nonetheless risks here.

- In March 2018, the House of Lords Select Committee on Communications (‘the Lords Committee’) launched an inquiry into internet regulation. The Committee published its final report, ‘Regulating in a Digital World’, in March 2019. The report reflects some of the themes of other initiatives, including the work of Doteveryone, NEF and the Carnegie UK Trust. It echoes Doteveryone’s call for a new co-ordinating body for sectoral regulators (here, it is called the ‘Digital Authority’); NEF’s call for greater algorithmic transparency and oversight (here, that is allocated to the ICO); and the Carnegie UK Trust’s recommendation for a new duty of care, to be enforced by Ofcom.

- In May 2017, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) launched an investigation into the use of data analytics for political purposes. This has resulted in various actions, including the publication of a report, ‘Democracy Disrupted? Personal Information and Political Influence’, in July 2018. The report calls for a statutory code of practice on the use of personal data in political campaigns and ‘a review of the regulatory gaps in relation to content and provenance and jurisdictional scope of political advertising online.’ These actions might bite on news publishers, if those publishers use the personal data of their audiences to disseminate political communications, but they have no bearing on journalism as such.

- In June 2018, the Electoral Commission published a report, ‘Digital Campaigning: Increasing Transparency for Voters’. Like the ICO, the Commission is concerned about the difficulty of enforcing aspects of electoral law online, and calls for greater transparency about political communications, and new powers to punish deter non-compliance. Again, these measures are unlikely to bite on press freedom unless they are applied to news publishers in their capacity as political campaigners.

- In August 2018, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) launched an investigation into social media influencers. This has resulted in various actions, including the publication of a ‘Guide for Influencers’, in January 2019, which aims to protect audiences from covert advertising.

- In September 2018, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) published an ‘Influencers’ Guide’, developed in conjunction with the CMA (see above). The work of the CMA and ASA on social media influencers is designed to translate existing advertising laws and regulations into the new digital environment, and does not change these underlying rules.

- In August 2017, the LSE launched the Truth, Trust & Technology (T3) Commission, which published its final report, ‘Tackling the Information Crisis’, in November 2018. The T3 report recommends the creation of a new ‘Independent Platform Agency’ (IPA), to encourage ‘the various initiatives attempting to address problems of information.’ The IPA would not regulate social media platforms, but would monitor platforms’ own attempts at self-regulation.

The Media Industry

Some initiatives are looking at the impact of online digital technologies on the media industry. These initiatives tend to be concerned with issues that affect broadcasting standards and the capacity of broadcasters to compete with online streaming platforms.

- In September 2018, the Office for Communications (Ofcom) published a discussion paper on the challenges of applying broadcasting regulation standards to online content, ‘Addressing Harmful Online Content’. Ofcom concluded that the norms of broadcasting regulation do not translate straightforwardly into a new media environment and made a number of constructive observations to inform future policymaking. It did not call for either new powers or the creation of a new body.

- In September 2012, the Media Reform Coalition, led by academics at Goldsmiths and Birkbeck, published a media democracy manifesto. This manifesto was updated and republished in March 2019 as ‘A Media Policy Fit for the 21st Century’. The manifesto supports the creation of a new ‘Institute for Public Interest News’, as recommended by the Cairncross Review (see below). It also calls for radical democratisation of the BBC and new measures to prevent monopolisation in all media sectors.

- In July 2018, Mark Bunting at Communication Chambers published a report, commissioned by Sky, ‘Keeping Consumers Safe Online: Legislating for Platform Accountability for Online Content’. Bunting proposes an oversight regulator for digital intermediaries, charged with upholding a statutory code of practice. This recommendation is broadly in line with the recommendations of the Commons Committee, Lords Committee and Carnegie UK Trust.

Journalism

Some initiatives are looking at the impact of online digital technologies on the news media in particular. These initiatives are particularly concerned with journalistic standards and the sustainability of public interest journalism.

- In March 2018, the Council of Europe formed a Committee of Experts on Quality Journalism in the Digital Age and asked the Committee to prepare a recommendation on ‘promoting a favourable environment for quality journalism in the digital age’. This work is ongoing. The Committee is likely to recommend statutory support for journalism that meets certain standards, in the form of subsidy and/or algorithmic prioritisation.

- In March 2018, Dame Frances Cairncross was appointed by the Government to conduct a Review of the Sustainability of High-Quality Journalism (‘the Cairncross Review’). She published her final report, ‘A Sustainable Future for Journalism’, in February 2019. The report calls for the creation of an Institute for Public Interest News (IPIN) to co-ordinate support for public interest journalism in the face of market failure. It also calls for regulatory oversight of a ‘news quality obligation’, whereby platforms would be responsible for prioritising high-quality journalism over low-quality journalism, misinformation or disinformation. The report does not specific which regulator should assume this oversight function, but it is reasonable to assume that Ofcom is first in line.

- In April 2018, the French-based NGO Reporters Sans Frontieres (RSF) launched the Journalism Trust Initiative (JTI), to set universal standards for trustworthy journalism in a digital era. This work is ongoing.

It will not result in any form of regulatory intervention, but seeks to ensure that existing regulators, press councils and certification bodies (such as Newsguard) follow a standardised approach to assessing journalistic credibility.

Conclusion

Of these initiatives, several call for the creation of a new public body. However, views vary widely about the role and remit of this body. There is some consensus around the need for an oversight regulator to enforce an ethical code on digital intermediaries, but opinions differ about whether this code should be set out in statute or left to intermediaries to define. Opinions also differ about whether the regulator should have powers of sanction and remedy.

In other words, there is no guarantee that the government is anywhere near recommending a body that will introduce ‘press regulation by the back door.’ In fact, it seems more likely that the White Paper will endorse calls for either Ofcom or a new body to assume some limited responsibility for overseeing self-regulatory initiatives by the digital intermediaries, with a veiled threat of more direct regulation down the line.

This article represents the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Media Policy Project, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.