On the 100th anniversary of the election of the first woman to take up a seat in the UK parliament, LSE PhD researcher and journalist Ruhi Khan looks at the history of attitudes to women in parliament, and the deep-seated prejudices that remain, perpetuated by media coverage.

On the 100th anniversary of the election of the first woman to take up a seat in the UK parliament, LSE PhD researcher and journalist Ruhi Khan looks at the history of attitudes to women in parliament, and the deep-seated prejudices that remain, perpetuated by media coverage.

A hundred years ago, on November 28 1919, Nancy Astor was elected and became the first woman Member of Parliament to take up her seat and enter Westminster. A hundred years later, in a series of shocking revelations, more and more women MPs are quitting parliament before the general election on December 12 2019. These women are young with a bright political future, but it seems they could no longer take the ‘horrific abuse’ and the toxic gendered culture that defines Westminster.

In 2018, the UK saw the centenary commemorations of the Representation of the People Act and of the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, that gave some elite women the right to vote and stand for elections. It was a momentous occasion and the Halls of Westminster played host to an exhibition on Vote & Voice, that charts the journey of women in Parliament.

Walking the hallowed halls of time, I realised how these early spaces of women in parliament (named for the rather claustrophobic and restraining conditions that women faced as they began to slowly occupy the Parliament) – the Ventilator (1818-1834), the Cage (1834-1918) and the Tomb (from 1918) echo in the politico-media discourse of today through the concepts of Invisibility, Sexism and Otherness.

Let me explain:

1. The Ventilator (1818-1834): Invisibility

In 1778, when women were banned from the public gallery of the House of Commons, some well-connected women who desired to watch the proceedings could do so through the ventilator shaft in the loft.

In 1778, when women were banned from the public gallery of the House of Commons, some well-connected women who desired to watch the proceedings could do so through the ventilator shaft in the loft.

This was the only space male politicians allowed women to peep through as long as they remained out of sight and were silent. Perhaps this attitude within the British political establishment that women are encroaching on a male space and require permission of the male gatekeepers is evident by the fact that only 32% MPs in 2017 elections were women and only 489 women have been elected over the course of one hundred years, while 442 male MPs were elected in 2017 alone.

In the media, this space of the Ventilator is symbolically representative of how women parliamentarians face exclusion from voicing opinion on more serious issues and are often pushed to the periphery:

- Female candidates receive less coverage in the media compared to men.

- The quality of coverage is mostly superficial.

- They also garner more negative coverage than their male counterparts.

By giving women less coverage on serious issues, the media ensures that women candidates are covered in a cloak of invisibility and are not strong contenders for leadership positions. While campaigning for the Speaker’s chair, Harriet Harman argued that it was imperative to get a second woman speaker in parliament, so that women MPs would be no longer “rendered invisible”. On 4 November, 2019, Lindsay Hoyle became the 157th male speaker in the House of Commons.

2. The Cage (1834-1918): Sexism

After the 1834 fire which destroyed the old Palace of Westminster and the Ventilator, the new House of Commons included a Ladies’ Gallery from where women could officially watch the proceedings of the House of Commons. Interestingly this gallery was situated high up above the Speaker’s Chair and had heavy metal grills over the windows and dim lighting which made this space small, crammed and dark and hence the moniker “Cage”. But the deliberate decision to install grills in the window and keep the gallery dark was to ensure that while women could peep into the proceedings, men could not see them and therefore not get distracted.

After the 1834 fire which destroyed the old Palace of Westminster and the Ventilator, the new House of Commons included a Ladies’ Gallery from where women could officially watch the proceedings of the House of Commons. Interestingly this gallery was situated high up above the Speaker’s Chair and had heavy metal grills over the windows and dim lighting which made this space small, crammed and dark and hence the moniker “Cage”. But the deliberate decision to install grills in the window and keep the gallery dark was to ensure that while women could peep into the proceedings, men could not see them and therefore not get distracted.

It is not surprising that the media uses women MPs as a distraction from serious parliamentary debates by objectifying and fetishizing them:

- The news focus is often on their appearance and personality.

- References to marital status and children take precedence over opinions.

- It’s mostly about legs and boobs and rarely about the mind.

Even in the 21st century female MPs are whoofed (Tasmina Ahmed Sheikh) and called hysterical (Mary Creagh) when they speak in Parliament. From “cantankerous bitch” (Edith Summerskill) to “bloody difficult women” (Theresa May), from an ape (Diane Abbott) to a pig (Mhairi Black) they have been called all by colleagues and others.

Reams of newsprint and its digital equivalent is used to compare women leaders’ clothes and legs rather than views and visions; or to crown them catwalk queens rather than discussing them as serious cabinet ministers. Even with the Brexit uncertainty looming large and economy threatened with a recession, the press simply could not move away from Theresa May’s boobs and dance moves even when she was the prime minister, the most important politician at that time. Now the Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson has accused the media of sexism with the leadership debates.

3. The Tomb (1918 onwards): The Other

Winston Churchill called Astor’s entry into parliament ‘embarrassing as if she burst into my bathroom when I had nothing with which to defend myself, not even a sponge’. To Churchill, Parliament was an old white gentleman’s club and women were the ‘Other.’ Perhaps it still is.

Winston Churchill called Astor’s entry into parliament ‘embarrassing as if she burst into my bathroom when I had nothing with which to defend myself, not even a sponge’. To Churchill, Parliament was an old white gentleman’s club and women were the ‘Other.’ Perhaps it still is.

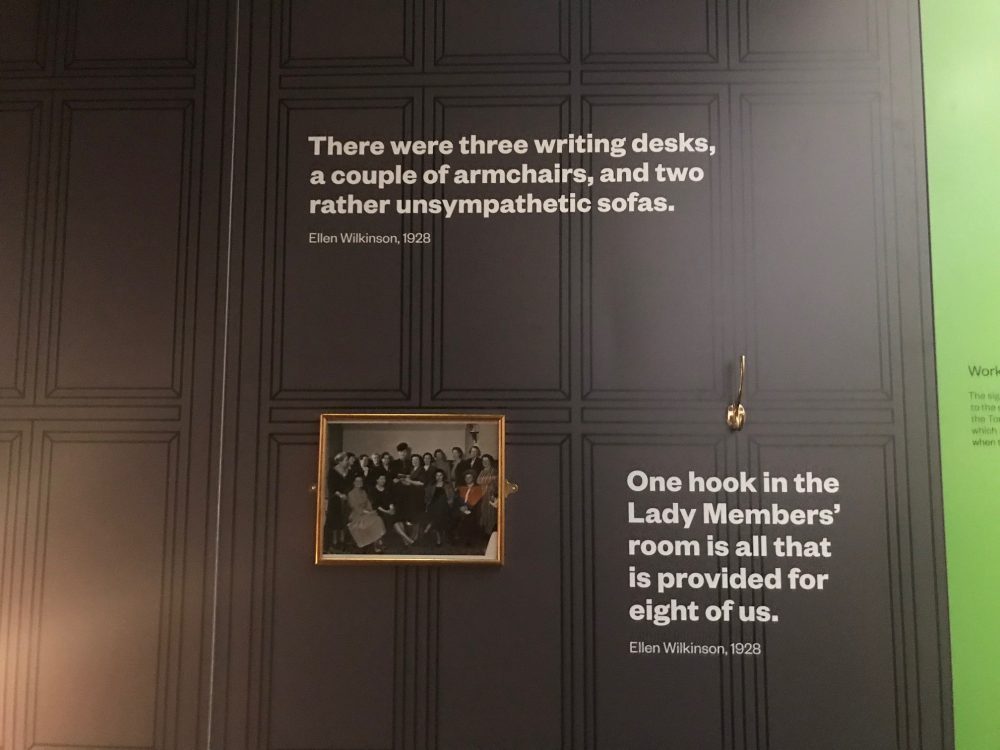

The first female MPs were given an office called the Lady Members’ Room (LMR), a small, barely furnished space that forced many women to sit on the floor to do their work and hold meetings along the corridors. Ellen Wilkinson mockingly called the LMR, ‘the Boudoir’ or ‘the Tomb’ and it became a refuge from the ‘enemy territory’- the rest of male-dominated Westminster. Add to this, the lack of toilets and restrictions on Commons Dining Room, and the early experiences of women in parliament were quite humiliating.

The male playing field remains

Understanding the implications of these physical spaces that once defined a woman’s place in this masculine world of high politics are important to gauge how they transform into gender discourses in politics and media. This highlights the barriers that women face in politics.

Now while women have moved from the LMR to their chambers, little else has changed. Parliament is still hostile to women who are pregnant and those suffering from ill health. The long and erratic hours forced on MPs make it particularly difficult for parents and carers, and women are made to feel guilty for taking maternity leave.

The media too assumes politics to be the playing field for men and automatically constructs woman as ‘the Other’ in contrast with the male political norm:

- While accessible to some women in lieu of their position as elected MPs, cabinet ministers and leaders, media outlets often prefer their male counterparts, even those who have retired to respond to current issues.

- It is not very inviting to their views on serious topics but focusses on domestic issues within Westminster like creches and housekeeping.

- Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) women MPs suffer most.

There have been loud and powerful women voices in Parliament over the years and more so today. Even with the exodus, a third of the candidates in this election are women, brave and determined to change politics. They need all the help they can get.

The #StopTheNastiness campaign launched by think-tank Compassion in Politics calls on candidates to pledge to campaign with respect and stand against the toxicity in politics. They encourage both politicians and public to call out hate. This should also extend to media reportage.

A century of discrimination and misogyny that has seeped into the deepest crevices of Westminster will not be easy to treat. What is required is a more systematic understanding of this gendered politics and a more structured action plan to dismantle it. Listening to women candidates and increasing women representation and diversity in Parliament is a good start.

This article represents the views of the author, and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.