In the lead up to Safer Internet Day (February 11), LSE researcher Mariya Stoilova asks whether we are better off at protecting children online than we were a year ago, and what have we learned about content regulation, industry responsibility, and age verification?

There has been rising pressure for internet regulation, both within the UK and internationally, and we have witnessed some significant developments, such as the UK government’s Online Harms White Paper, which the new government plans to action, and the publication of the Age appropriate Design Code by the Information Commissioner’s Office.

In the international arena, we saw the drafting of a General Comment on children’s rights in relation to the digital environment by the Committee on the Rights of the Child and the announcement that the US Federal Trade Commission is to review the operation of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act Rule (COPPA). There were important setbacks as well, such as the abandonment of the proposed UK Internet age verification system in October 2019 and the findings from the Global Threat Assessment (WePROTECT Global Alliance) that online child sexual exploitation and abuse – in its scale, severity and complexity – is increasing faster than its prevention and response. In spite of the progress, we are still facing important questions, particularly in relation to what shape online safety regulation should take, and whether it should come from government or industry.

A recent Westminster eForum event on child online protection summarised the latest evidence and thinking around content regulation, age verification and industry responsibility. Below are some highlights from the speakers.

Protecting children online – key issues and emerging trends

Pointing to her work on children’s online activities, risks and safety and recent reviews of the existing evidence for the UK Council for Internet Safety (2017) and UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti (2019), Professor Sonia Livingstone (London School of Economics and Political Science) argues that, overall, there is very little evidence of increased online harm for children. While online safety is a problem which on a social level affects everyone, on an individual level fewer children experience online risks with the most severe cases of harm affecting very small fractions of children. The situation is often misrepresented in the media where scary stories prevail, often misrepresenting the evidence and fuelling public anxiety about children’s online safety, while the evidence suggests otherwise. Still, it matters that even small proportions of children are exposed to online harm and it is evident that we need to take appropriate and much better action than we have so far. So, when we are asking, what are the pathways to harm and what are the sensible points of intervention, there are a few points of consensus in the evidence which should guide our efforts:

- The available evidence suggests the causes of harm are likely to be multiple, yet they are rarely disaggregated

- It is also likely that long-standing risks and harm to children increasingly have a digital dimension

- And that the visibility and publicity surrounding the digital increases children’s overall reporting of risk and harm

- It may be that the digital amplifies adverse effects, though it also provides new opportunities for intervention

- Crucially, vulnerability factors affect children’s online risk and harm; hence a negative spiral of multiple risks for some

Where next for protecting children online – priorities for industry and regulation

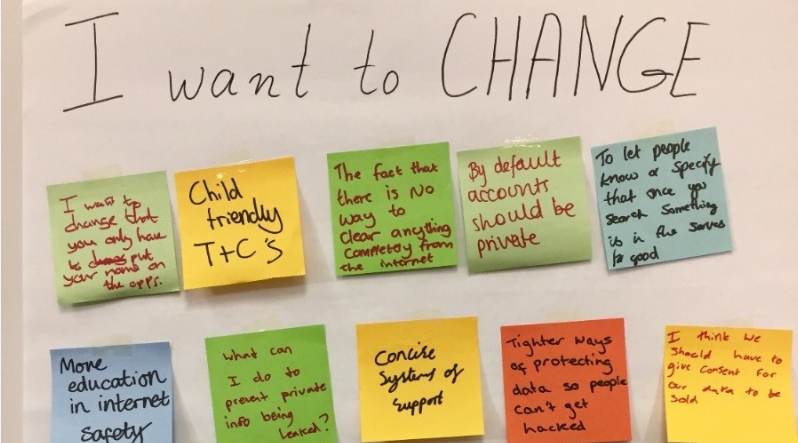

- Recognise and build on children’s own concerns and strategies (Will Gardner, Childnet International and UK Safer Internet Centre): while everyone has a role to play in keeping children safe online – industry, the Government, schools, parents – it is important to empower children and harness their own passion for the issue of online safety. The UK Safer Internet Centre runs many initiatives which create opportunities for children have a positive impact on their peers and online communities, focusing on issues such as cyberbullying, online sexual harassment, online safety. The Centre organises annual activities for the Safer Internet Day on February 11. The theme for 2020 is Together for a Better Internet with the hashtag #freetobe focusing on children’s online identity and the question of whether they are free to be whoever they want online.

- Focus on where the risk turns to harm (Claire Levens, Internet Matters): screen time tops the list of parental concerns about children’s online safety alongside issues such as sexual content, online bullying, and contact with strangers which consistently remain very high up in parental worries. Internet Matters focuses on creating resources based on evidence to support parents and professionals on a whole range of issues related to children’s online safety but focusing on where risk turns to harm is most important. This is where the risks are most acute – for example, when transitioning from primary school to secondary school or when we have children and young people facing vulnerabilities. Understanding offline vulnerabilities will help to predict online risky behaviour. To address these issues we need a wide societal response, a better e-safety education, and meaningful and efficient up-skilling of professionals working with children.

- The internet is mostly unregulated and this has to change (Alex Towers, BT and techUK): while we undoubtedly need to protect the opportunities that the internet has brought, it is important to acknowledge that the responsibilities of companies operating online are much less than those in other spheres. For example, in comparison to TV, the internet is lightly regulated. The question is how to regulate it so that we keep the balance between guarding online freedom and privacy and protecting vulnerable populations. Many companies work to protect children online, whether by developing filters and parental controls, removing or blocking child sexual exploitation content, or working closely with law enforcement agencies, but there is clearly more to do. The industry is progressing towards creating new private, encrypted, unregulated spaces but before this happens we need to think more about the effects of this on child protection and we need more regulation. There are currently multiple regulators, processes, and pieces of legislation concerning online harms, while co-operated and combined efforts and a joint framework would work better.

- There should be a statutory duty of care (Professor Lorna Woods, University of Essex): the Online Harms White Paper proposes establishing in law a new duty of care towards users, which will be overseen by an independent regulator. Companies which design digital platforms and services will have an obligation to prevent against reasonably foreseeable harms. The efforts need to be proportionate to the resources available to the company and appropriate for their audience and service provided.

- Clarifying the grey areas should be a state responsibility (Ben Bradley, techUK): the systemic approach of the Online Harms White Paper is welcome but clearer regulations are still needed when it comes to what is and isn’t acceptable to do online, how to define the subjective nature of harm, or how to balance conflicting rights of users. By not being specific enough in its regulation, the state hands over its decision-making responsibility to technology companies. A further step in the right direction is producing a media literacy strategy which can empower and educate users of all ages to navigate the online world safely and securely.

- A digital environment that respects all children’s rights (Claire O’Meara, UNICEF UK): when we focus overly on harm, we limit other types of child rights online, as the digital environment can create both opportunities and challenges to children. It touches upon multiple rights, many of which are positive and important for child development, such as rights to privacy, access to information, and freedom of expression. Finding the balance between different rights is difficult and requires collaboration between government and non-government agencies, industry, civil society, parents, and children.

- More attention to vulnerable groups (Bernadka Dubicka, Royal College of Psychiatrists): we don’t hear enough from children from vulnerable groups, such as children with learning disabilities, autism, mental health problems, or those living in poverty. These children are disproportionately affected by online harm, and we need to know more how to protect them from risks and to train better all professionals working with vulnerable children.

This article represents the views of the author, and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.