The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office is in the process of putting together an age-appropriate design code, which will outline the standards that providers of online services which process personal data and are likely to be accessed by children will be expected to meet. Here, LSE’s Mariya Stoilova, Professor Sonia Livingstone and Rishita Nandagiri offer advice to policy makers, based on the findings of their Children’s Data and Privacy Online project, which involved asking children what they want to change. [Header image credit: Cavalier92-CC-BY-NC-ND-2]

The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office is in the process of putting together an age-appropriate design code, which will outline the standards that providers of online services which process personal data and are likely to be accessed by children will be expected to meet. Here, LSE’s Mariya Stoilova, Professor Sonia Livingstone and Rishita Nandagiri offer advice to policy makers, based on the findings of their Children’s Data and Privacy Online project, which involved asking children what they want to change. [Header image credit: Cavalier92-CC-BY-NC-ND-2]

With growing concerns over children’s online privacy and the commercial uses of their data, it is vital that children’s understandings of the digital environment, their digital skills and their capacity to consent are taken into account in designing services, regulation and policy. In November 2019, the Information Commissioner’s Office will conclude its review of 450+ consultation responses on its Age-Appropriate Design Code for the Secretary of State (as part of the Data Protection Act 2018). In the US, the Federal Trade Commission is consulting on the next steps for the Child Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). At some point, one hopes, the European Commission will review implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation to determine whether it is serving children’s interests.

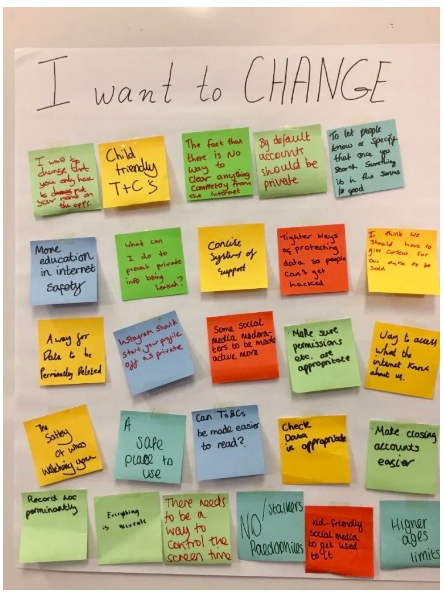

Our project on Children’s Data and Privacy Online sought to listen to children’s voices and develop tools to better empower them to understand and manage their data and privacy online. We conducted focus group interviews with children around the UK, and built an online toolkit to explain to children where their data goes.

But why should policy makers be interested in our findings? And what do we expect them to do next? We’ll begin with what children say they want to change, as befits our child-rights approach.

What children want from policy makers and industry

In each focus group we invited children to share what they would like to know about their online data and privacy and, second, to list the things that others (parents, educators, regulators and companies) should do differently to make privacy better.

In each focus group we invited children to share what they would like to know about their online data and privacy and, second, to list the things that others (parents, educators, regulators and companies) should do differently to make privacy better.

Children’s want to know how their data flows online, how long it is kept and how it is used. They also want clearer Terms and Conditions, more free content (e.g., fewer in-app purchases), for apps only to collect data that is necessary, not sharing children’s data with other companies, prevention of data leaks and to be able to permanently delete online information. These are the priorities as children see them, and the main demands that they have for regulators and industry.

As we also heard from them, children do not think that others (adults) listen to their opinions, suggestions or complaints, and they are keen for their voices to be heard more. They experience the digital environment as quite dismissive of their needs and personal preferences. And they expect the internet to be fair, and for parents, educators, regulators and companies to act responsibly and in children’s interests.

While children can be practical and understand that the commercial model behind the apps they use requires their participation (e.g., that sometimes they have to watch an advert to unlock some content), they also become critical and frustrated when things do not work as they should and nothing is done to fix the problems they encounter (e.g., when they report an incident online and do not hear back).

What should policy makers and industry do?

Based on our review of the empirical literature with a special focus on the relation between age and understanding, and on and what children told us, our six top recommendations for policy makers are:

- Child rights-respecting policies must promote autonomy, balance protection and participation, and prevent discrimination and other harms.

- Distinguish privacy in interpersonal, institutional and commercial contexts, and ensure policies are context-appropriate and clearly comprehensible.

- Sustained media (data, digital, critical) literacy is vital from an early age – in school curricula and teacher training – but it is not a ‘silver bullet’ solution.

- Regulate for privacy-by-design and by-default, and provide child-friendly age-appropriate mechanisms for privacy protection, complaint and remedy.

- Support children by supporting parents, schools and the organisations that work with families and vulnerable children.

- Sustain a robust evidence base that fills key gaps (e.g. include younger children), evaluates the effectiveness of interventions and consults children.

(For more on these recommendations, see our policy brief and our full findings.)

We’d say something similar to industry, namely:

- Respect child rights, promote autonomy, balance protection and participation, and prevent discrimination and other harms.

- Ensure company policies and practice are context-appropriate and clearly comprehensible to your actual users.

- Opt for privacy-by-design and by-default, and provide child-friendly age-appropriate mechanisms for privacy protection, complaint and remedy.

- Support children’s media (data, digital, critical) literacy and allow children of different ages to gradually develop the needed digital skills by crating age-appropriate content and design.

- Help children by supporting parents, schools and organisations that work with families and vulnerable children.

(For more, see our industry brief and highlights from our findings.)

Policy makers must act, because education alone cannot solve the problem

We earlier addressed the role of teachers and schools, recognising that the task of improving children’s understanding of the data ecology and their rights within this largely falls to them. That’s why we built our online toolkit – do check it out at www.myprivacy.uk

But as we have argued before, education alone cannot resolve all the challenges of a datafied world. Children cannot learn what is impossibly complex. Teachers cannot teach what they themselves don’t understand. So the digital environment must be made more child-rights-respecting, and more navigable by everyone.

Most important, the present take-it-or-leave-it (or, “give us your data or miss out”) digital environment mitigates against user responsibility. So for industry, probably in tandem with policy makers, the time is right to develop a better-designed digital environment that enhances understanding and offers people – young and old – more meaningful choices

This article originally appeared on the Media Policy Project blog and has been reposted here with permission.

This article represents the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.