Tablets beat all other devices in terms of popularity amongst small children. Sonia Livingstone discusses her recent research on uses, skills and the family context of technology users who are yet too young to read or write. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

In autumn 2014, as researchers from across Europe, we spent time interviewing and observing in the family homes of 6- to 7-year-olds and their younger siblings. We talked to parents, looked at how digital media were dispersed around the house, chatted to and played with the children, and asked them to show us what they do online. We were concerned that, despite huge interest from parents, policy-makers and the public on how families are responding to the influx of digital media in the home, the vast majority of available evidence relates to older children, and mainly teenagers.

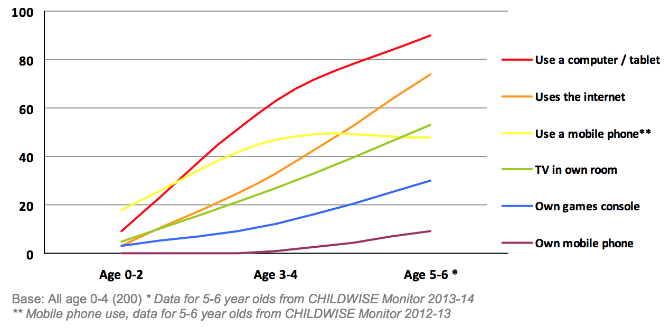

In the UK and elsewhere, children are getting online younger and younger, as shown in this figure from CHILDWISE:

So what did we discover?

Tablet takeover

In just a few short years, the tablet has become the ‘killer device’, favoured at home in general, and among younger children especially. Apart from hand-held games devices, children don’t usually own the devices, but they commonly share family devices or borrow from parents (especially their smartphone).

The tablet’s touchscreen interface means young children can use them independently at an earlier age than a laptop (since often their lack of basic literacy means they can’t use a keyboard). Mainly they play games – typically, just a few games played over and over – although they also use portable devices to watch films, videos and television, including streaming, on-demand and catch-up services.

Parents focus on ‘valued’ uses, but for children it’s all about a fun way to fill in the gaps in the day

When we talked to parents, they tended to tell us about the purposive ways that children use digital devices for learning, fun or communication. Of course they recognised that the devices are also useful for filling the gaps in daily life when parents are busy and children need to be entertained (when parents are shopping, cooking, phoning, driving, or just sleeping in the early mornings).

But it seemed they underestimated how common these gaps were – the children told us about lots of personalised or private use when parents were not around. That makes for lots of ‘screen time’ when parents are not really supervising or, perhaps, supporting imaginative or stimulating uses of technology. So, like television before it, the tablet or smartphone is often most useful as ‘an electronic babysitter’. As technology changes, families’ attention has surely shifted away from one big screen towards multiple small screens and we’ve discussed various strategies for parents to manage their kids’ media use in a recent blog post.

Credit: S. Livingstone & S. Ottovordemgentschenfelde

Credit: S. Livingstone & S. Ottovordemgentschenfelde

It was also noticeable that when parents want to show how they are ‘good parents’, they talk about shared non-digital activities (going to the park, sports, or craft activities at home), although enjoying a TV programme or film together on the sofa is also seen as good parenting.

Have children got the digital skills? This is hard for parents to judge

We saw children use a limited range of online resources, often assisted or overseen by parents or older siblings. Even the youngest recognise the YouTube icon (and know how to click on the recommended links on the right-hand side), while Skype or Facetime is familiar in transnational families.

While 6- or 7-year-olds can navigate some devices or apps with confidence and pride, skill in one area doesn’t imply skill in all others. Both children’s skills and some of their limitations can be misrecognised by parents – at least until the child comes to report a problem, which is often when parents get involved. Understanding what ‘online’ means, who put content there and why, or how to evaluate what’s good or bad for them – children have little grasp of any of this, and parents don’t seem very concerned.

But there are many differences across families. In some, parents deliberately ‘scaffold’ or structure their child’s learning, and in others, parents are themselves skilled and diverse users, so their children learn just by being around them. The same applies to older siblings. But in some homes, parents are nervous of the technology, or they see their own uses as very separate from their children’s, and so their children have little opportunity to pick up skills.

Digital media are routine, embedded in everyday life, but not dominating

But let’s not get carried away that young children’s lives are changing in every way. They still lead active, varied lives in which technology plays an important, but not dominating, part. Technology use is balanced with many other activities, including outdoor play and use of non-digital toys. But very young children try to do what they see older siblings and parents doing – and if they are always staring at a screen, the little ones will want to do the same.

Worth thinking about

- Although they’ve heard media stories about online risks, we found parents generally unconcerned, although some had worries about violence or pornography or health risks. And indeed, there are such risks of harm, although they’re not as common as some fear.

- The children didn’t report many worries to us either, and although they knew what was worrying their parents, they didn’t really understand why. But this age group really respects and values parental input, so it could be a good time to discuss values and choices, starting as young as possible, and well before significant problems arise.

- Does repetitive play or use of just a few sites matter? Children have always loved to play the same games or read the same books over and over. But it’s still worth asking whether their online activities are really imaginative or stimulating, offering some kind of progression or learning. We were struck by how few children used educational apps, and how difficult parents found it to articulate just how and why digital media could be beneficial, beyond a general positivity. What would be good uses of the internet?

- Parents are trying to manage their children’s digital activities, but they tend to see these as an occasion for reward or punishment rather than learning or creativity, and they tend to impose restrictions on use (including using time-based rules that little children cannot understand) rather than guiding children towards really beneficial or diversified activities.

- How can parents gain the advice that many would welcome? Many look to their child’s school, but schools, it seems, have not yet recognised young children’s digital lives, although they surely have expertise and ideas they could share with parents at home. ParentZone’s new initiative Parent Info may be helpful here.

- Last, what’s the role of commercial providers here? We saw lots of children using content designed for older groups, lots using free apps with commercials because parents choose not to pay, and lots struggling with interfaces based on print or hard-to-use navigation. Dress-up and shoot-em-up games are fine in their place, but is this the best we can do to ‘fill the gaps’ in our children’s daily lives? Are child versions of familiar sites a good idea? Consider YouTube’s new service especially for children, which is proving controversial. If publicly funded sites are preferable, which organisations will provide them and how are parents to find them?