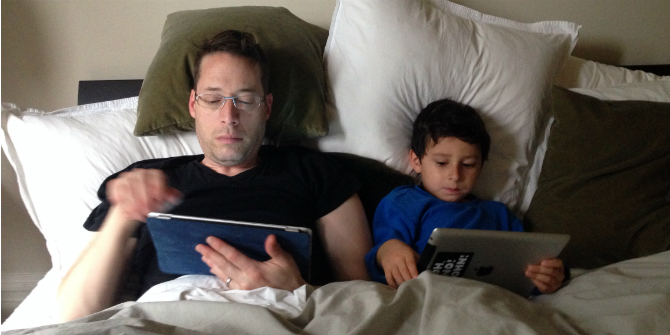

What do children ‘do’ in school? Sonia Livingstone sheds some light on the ‘mysteries’ of the school day. Together with Julian Sefton-Green, she followed a class of London teenagers for a year to find out more about how they are, or in some cases are not, connecting online. The book about this research project, The Class: living and learning in the digital age, just came out. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project. [Header image credit: S. Lilley, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

What do children ‘do’ in school? Sonia Livingstone sheds some light on the ‘mysteries’ of the school day. Together with Julian Sefton-Green, she followed a class of London teenagers for a year to find out more about how they are, or in some cases are not, connecting online. The book about this research project, The Class: living and learning in the digital age, just came out. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project. [Header image credit: S. Lilley, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

When I tell parents that I’ve spent some months with a class of 13-year-olds, it’s clear that the very notion of ‘the class’ has a curious fascination, suggesting a closed, intense, yet fragile world. Fuelling this fascination are the plentiful fictional portrayals of school life in popular culture. Think of the beloved teacher in Goodbye, Mr Chips, the charismatic teachers of Dead Poets Society or The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, the idealistic community school in rural France, or the dystopian Class of 1984. These build on a long history of novels set in the closed world of boarding schools, of which Tom Brown’s Schooldays is probably the best known.

Nostalgia for childhood

Perhaps the appeal of these is that they invite us to remember – or to re-imagine – the intensely felt, bounded world of our own childhood, whether we recall this with rose-tinted nostalgia or a shudder of horror. For us as researchers the value is two-fold. First, mention of ‘the class’ invites our readers to bring vividly to mind how life used to be for children and to compare it with today. Second, it activates myriad normative hopes about how life should be, making people ready to debate whether that seemingly closed world is a ‘good thing’ (child-centred, protective, free of adult problems), or not.

Historians argue that, once past infancy, childhood as a distinct period in the life course only became recognised as something to be protected with the development of modernity itself – including the emergence of the nuclear family, the school and accompanying changes in the nature of work and the importance of literacy. So the school is not only a place of education, but also of moral and social development designed precisely for those who lack the literacies (print, critical, social) to engage independently with the wider world.

Learning all the time

Hence the radical drive of many educational reformists to challenge the equation of innocence and ignorance in childhood, instead insisting that children are learning all the time, outside school as well as within it, and that what they know should be recognised and valued. In today’s digital age, the ‘walls’ of the school, which keep education away from home and community, is under siege from new learning opportunities outside school and the use of networked digital devices (sanctioned or not) at school. While many regard these technologies as problematic, leading to bans by many schools, a positive view can be found in the notion of ‘connected learning’, which seeks to harness digital media to connect learning at home, school and community in constructive, creative, child-centred and collaborative ways.

Our project was partly inspired by Laurent Cantet’s 2008 award-winning film, Entre les Murs (‘Within the walls’, translated as ‘The class’), which follows a year in the life of an optimistic young teacher of a class of 14- to 15-year-olds. It shows how the students’ diverse family contexts shape their chances of learning, resulting in levels of inattention or hostility that the teachers find problematic. When our hero encourages his students to represent their personal life histories within a creative writing lesson, unmanageable tensions erupt. Then the formal power of the school steps in, taking the side of the teacher to the detriment of an already-disadvantaged student. This leaves a somewhat damaged class to continue its daily routine, now more conservative and less idealistic than before. Its message proved telling for our project.

Connecting learning

In our class we saw efforts both to connect sites of learning to enable a holistic approach, and efforts to disconnect home, school and community on the part of teachers, parents and the young people themselves (check out this case study). How can we decide if the class is best left as a world of its own or whether policy-makers should try to embed the class in its wider community, even perhaps supporting the ‘schools without walls’ movement? We suggest it depends on:

- Whether connected learning sites, including those underpinned by digital networks, genuinely facilitate socially progressive change – supporting learning, creativity and youth participation, as well as focusing resources on disadvantaged groups.

- Whether such efforts are instead driven by the interests of powerful political and commercial interests, including the big technology providers.

In short, is education best left to schools, or is it too important to leave just to them? And does digital technology help or hinder? These questions are on the minds of many parents as they try to support their children’s learning, knowing its importance to their future life chances, yet not always equipped to intervene constructively.

Family life

But it is hard for both parents and teachers to work out their own priorities when teachers know little of their students’ home lives, while parents know little of their children’s life at school.

Indeed, we heard teachers express both curiosity and scepticism about family life – seen as timewasting, ineffective, or just plain mysterious – notwithstanding their use of homework tasks, planners, emails and phone calls to parents designed to ensure that the rigour and ethos of school extends beyond its gates.

Parents were often less critical of school but still, it was largely a blank to them, leaving them unclear about their child’s daily experience (since children, famously, say that ‘nothing’ happened at school) and uncertain about how best to play their role.

Finding ways to improve communication, without necessarily collapsing socially distinct boundaries or bringing outside difficulties into classrooms ill equipped to deal with them, remains a pertinent challenge in this supposedly connected world.

NOTES

The class: Living and learning in the digital age, published in May 2016, is based on a research project funded as part of the Connected Learning Research Network by the MacArthur Foundation’s Digital Media Learning initiative.