As the UK – along with many other countries around the world – remains in lockdown to quell the spread of COVID-19, the government is searching for ways to bring an end to the restrictions on movement without triggering a resurgence of the disease. LSE Professor Robin Mansell discusses whether encouraging widespread use of a contract-tracing app is a proportionate response to the current health crisis.

As the UK – along with many other countries around the world – remains in lockdown to quell the spread of COVID-19, the government is searching for ways to bring an end to the restrictions on movement without triggering a resurgence of the disease. LSE Professor Robin Mansell discusses whether encouraging widespread use of a contract-tracing app is a proportionate response to the current health crisis.

It seems likely that a decision will be taken soon in the UK to use a smartphone (Bluetooth) based contact tracing app to help stem the COVID-19 pandemic, with a trial reported on 22 April. Used with other measures including scaled-up testing for infection, physical distancing and self-isolation, this is expected to help save lives. There is growing amount of scientific literature on the rationales for a scaled-up introduction of a contact tracing app. A more widely-informed debate about whether an app is needed and, if it is needed, whether it is a proportionate response to the COVID-19 crisis, is essential. There is currently little evidence of an inclusive public debate about the rationale for nationwide use of a contact tracing app. Popular accounts presume that the crisis justifies the introduction of a contact tracing app, albeit with assurances about privacy protection. The claim is that an app will yield ‘actionable insights’ for combating the spread of the coronavirus.

That COVID-19 is a ‘serious and imminent threat to public health’ is rightly uncontested. But in the UK, the public is not being provided robust information as a basis for making a choice about whether or not to use a contact tracing app if one is sponsored the NHS. The science and technology debate about these apps typically is presented as a trade-off between individuals’ health and their privacy. There is a debate about the societal moral and ethical issues, but there is little visibility of a debate about the incentives guiding government choices and company practices. Apart from occasional reference to the risk of mission creep once the virus is contained, the impacts of wide scale use of contact tracing for people’s autonomy to live their lives without all-pervasive monitoring is barely mentioned in the mainstream press. Yet a letter from 300+ scientists and legal experts explains that there are trade-offs in any app design and that mission creep would ‘catastrophically hamper trust in and acceptance of such an application by society at large’. Dutch researchers in a recent letter to their Prime Minister say ‘whether we like it or not, these apps will set a precedent for future use of similar invasive technologies, even after this crisis’.

Assuming App Adoption, What are the Choices?

Worldwide, contact tracing is being introduced in response to the pandemic, with some apps being much more data intensive than others. The European Union eHealth Network lists dozens of initiatives. A Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT) consortium is using Bluetooth and pursuing a privacy-preserving approach, but the devil lies in the details – one set of design choices (a centralised approach) uploads user data to a centrally controlled data base. Another set of choices (a decentralised approach) minimises the amount of data flowing to a central data base. A different initiative, Decentralised Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (DP-3T) clearly favours a decentralised solution and some researchers have withdrawn from the PEPP-PT due its ambiguity of approach.

In Europe, the General Data Protection Regulation establishes conditions under which app user consent can be said to have occurred, but does not apply to non-personal data. The European Data Protection Board’s Chair has confirmed that ‘data protection rules do not hinder measures taken in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic’, but notes that location data can only be used when they are made anonymous or with the consent of individuals. The European Data Protection Supervisor notes that if anonymised data are used, it is insufficient simply to remove obvious identifiers. A Council of Europe recommendation emphasises that governments should ‘endow their relevant national supervisory, oversight, risk assessment and enforcement institutions with the necessary resources and authority to investigate, oversee and co-ordinate compliance’. Consent must be freely-given, specific, informed, and unambiguous. Even though the UK has left the EU, it still has legislation to underpin such assurances. In a global framework, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, says that ‘if States do not act with within a human rights framework, a clear risk exists that the measures taken might violate economic, social and cultural rights’. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Access Now, Privacy International, and 103 other organizations have issued a statement emphasising that any app that is adopted must be lawful, necessary and proportionate, transparent, and justified by legitimate public health objectives.

If introduced, a contact tracing app needs to be used by around 80% of the smartphone user population to be effective. The only way to achieve that is through a massive advertising campaign convincing people that adoption will help save their lives. It is unlikely that the risks will be spelled out for the wider public. Instead, the government will give assurances about data security: NHSX’s Matthew Gould, promises strict anonymity controls with principles of openness and transparency to ensure that individuals cannot be identified. Michael Gove says he thinks the ‘overwhelming majority’ of people will want to download it’ – yet there is only hypothetical UK survey evidence suggesting that a majority of a representative sample of 1,055 respondents would welcome an app. The rationale is that people will consent to app use on the basis of an informed choice, but if they are to do so, they must know something about choices that have been made. At present, this is not feasible.

The fact that there are concerns is not easily discoverable by the wider public. In March 2020, UK legal experts and other social scientists signed a letter to the CEO of NHSX and The Secretary of State for Health and Social Care observing that ‘testing times, do not call for untested new technologies’. They call for an expert oversight panel with public and patient participation to ensure human rights are protected. Chris Whitty, Chief Medical Officer for England, has said that ‘I am very much against giving any patient-identifiable information …. I am not in favour of going down to street level or “you are within 100 metres of coronavirus”. That is the wrong approach for this country’. Yet much faith is being placed in the protections offered by anonymised data and government oversight.

Signs of ‘Data Opportunism’?

Government decisions are at risk of over-reliance on data. NHS England and NHSX are developing a data platform to connect government and other social care data sources creating a dashboard or a ‘single source of truth’ to guide COVID-19 resourcing decisions. Work is said to be undertaken with trusted partners using strict contractual conditions concerning access to, use of, and, ultimately, deletion of data. But the default position is that ‘we need the private sector to play its part’ and the contributions of Microsoft’s Azure cloud platform, Palantir Technologies UK, Amazon Web Services and Faculty, a UK based AI tech specialist, as well as Google and Apple are welcomed. NHSX has been working on an opt in coronavirus contact tracking app. The specific design (centralised or decentralised) choices and the extent of the involvement of Apple and Google in the UK app trial are hard to discern. When it comes to scaling up, 21% of UK adults do not own a smartphone, rising to 60% for those over 65. Alternatives will be needed if they are not to be excluded from the potential health benefits.

The overriding belief is that contact tracing apps will be used ‘for good’. It will be argued that the risk of data breaches and de-anonymisation is very low or non-existent. Amnesia seems to have taken hold. Many of the companies involved in app development are the same ones that, before the crisis, were the focus of concern because of their handling of data. Little, if any, information is available about money flows or the incentives of companies participating in app development. The Online Harms White Paper led to pending, albeit controversial, legislation to prevent the largest digital and AI companies from engaging in illegal and harmful data practices. Their history of evasion of public accountability is not part of the contact tracing app discussion. When advocacy groups have developed tools to enhance data collection transparency, they have been shut out. So far, there is no hint that an independent oversight body will be put in place, nor is there evidence of a consideration of a wholly non-commercial alternative for a contact tracing app.

Journalist Tasnim Nazeer sees ‘data opportunism’ when these apps are deployed in China and Russia. Surely if they are to be used in the UK, the choice to do so should not rest with a cohort of politicians without independent public accountability. If the government authorises a contact tracing app, the rationale and design choices should be transparent, not only to the research community, but to a wider public. Without information, the potential app user who is invited to opt in will not be making an informed choice.

Scrutiny of privacy-by-design and principled ethical decisions is crucial. But it is not sufficient. Contractual agreements involved in delivering an app need to be available for independent public scrutiny. A debate also is needed about what is likely to happen when people become habituated to using a contact tracing app and the risk that this will open the door to broader surveillance once the crisis recedes. A society that ‘subordinates considerations of human well-being and human self-determination to priorities and values of powerful economic actors’ as Julie Cohen puts it, cannot be said to be a democracy.

This article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

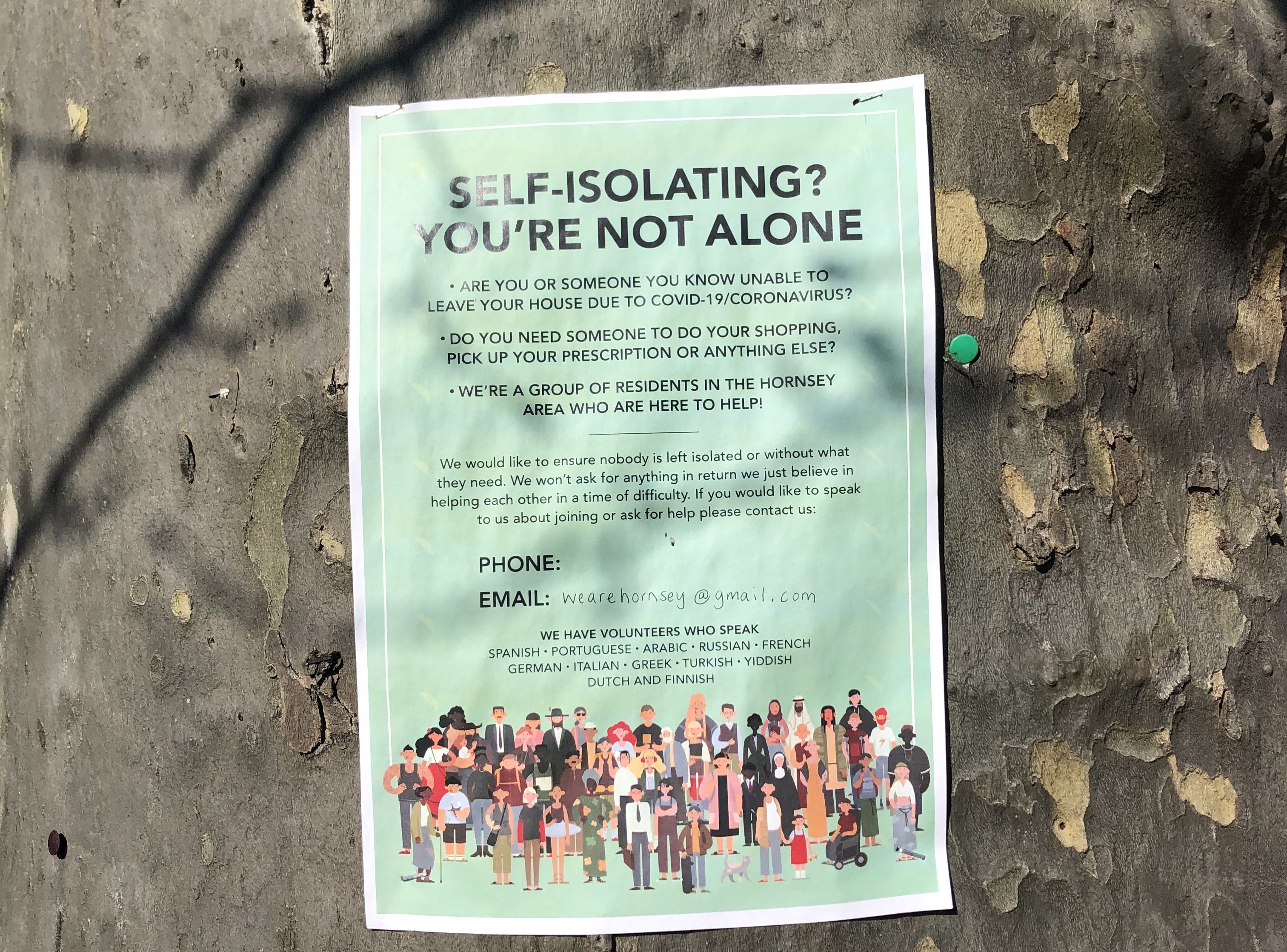

Featured image: Photo by Rob Hampson on Unsplash