Dr. Anna Tashchenko of the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv writes here about her research that identifies dominant visual value patterns in the images that accompany media reports on the Russian war in Ukraine and the media stories of Ukrainian refugees.

Dr. Anna Tashchenko of the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv writes here about her research that identifies dominant visual value patterns in the images that accompany media reports on the Russian war in Ukraine and the media stories of Ukrainian refugees.

———————————————————

To my beloved mother Alla, grandfather Kazymir, and foster father Iurii, who are already invisible for me.

Nothing new under the moon

An interview with Ukrainian public philosopher Andrii Baumeister on June 23 proclaimed ‘a post-value world’ due to the unprecedentedly high level of uncertainty, uring the full-scale Russian war in Ukraine. I take the position that such a term could give rise to false nostalgic ideas, just like the term ‘post-truth’. Sheila Jasanoff and Hilton R Simmet remind us that truth in public space has always been ‘demonstrable truth’ – accordingly, it is logical to assume that, instead of lamenting pure values and their loss, we should remember that there were, are and will be ‘demonstrable’ values, and that values retain their potential to characterise the deep foundations of culture.

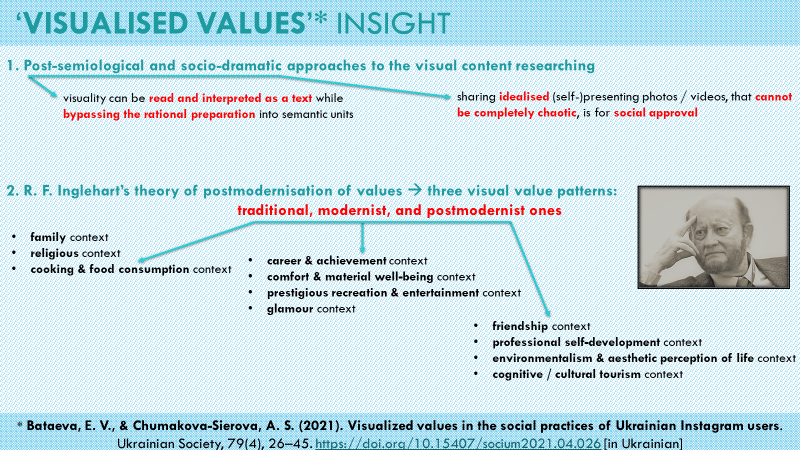

Shortly before the beginning of the war, the idea of ‘visualised values’ was born in the professional sociological community of Ukraine, as defined by Iekateryna Bataieva and Anastasiia Chumakova-Sierova. This allowed for the recognition of cultural values – traditional, modernist, and postmodernist – in the non-articulated meanings of visual images, and I applied this to my analysis of wartime images.

Image 1: A brief description of the visual operationalisation

Visual construing of ‘modern nation fathers who care’

Firstly, I analysed the illustrations from a sample of news in English by state news agency ‘Ukrinform’ in the first three weeks of Russian war in Ukraine. The illustrations very rarely related to the story in the news directly – rather, they offered hints of what was happening, certain symbols, and invited the viewer to perceive the text with complete believing in the truthfulness of what was written. Modernist values prevailed, due to the dominance of the contexts of achievement, material well-being, and glamour, because the illustrations were dominated by close-up depictions of good-looking Ukrainian / world politicians and military men against the background of status attributes (national /state symbols, media titles, event titles, big chairs, big offices or conference halls, etc.). Photos of powerful men prevailed on Ukrinform in comparison to photos of powerful women, but Ukraine is currently in a phase when, again, both women and men are accepting the challenges of wartime, finding the inner strength to survive, changing themselves, changing attitudes towards themselves and the world, re-understanding themselves and their contribution to victory.

Image 2: Selection of photos from Ukrinform images’ sample

The photos also showed many kinds of military equipment and civilian infrastructure (photographed mostly in a damaged condition, so, it was about ruined material well-being), and digital or natural aesthetics (i.e., elegant illustrations of the global Internet network or beautiful nature – most often, the sky).

As a whole, the strategy of illustrating wartime news provided a logical and constructive narrative of ability to influence the trajectory of war at the macro-level of social interactions by people in power. To many Ukrainians, directly and indirectly affected by death and destruction of livelihoods, the images of power (especially of power in action) offered a message of faith and hope. They were informed through words and images that there was someone there, portrayed in big chairs and offices, who negotiated, held talks, meetings and conferences, spoke to foreign parliaments, all in efforts to affect change. Thus the common Ukrainians, who make up the majority of those affected by war, were visually reassured that, in addition to their own efforts, there were far more powerful forces – politicians, military, experts, writers, journalists, charity actors, etc., – who really could end the war.

Image 3: The ratio of the visualised values identified on Ukrinform

Visual construing of Ukrainian people fleeing war

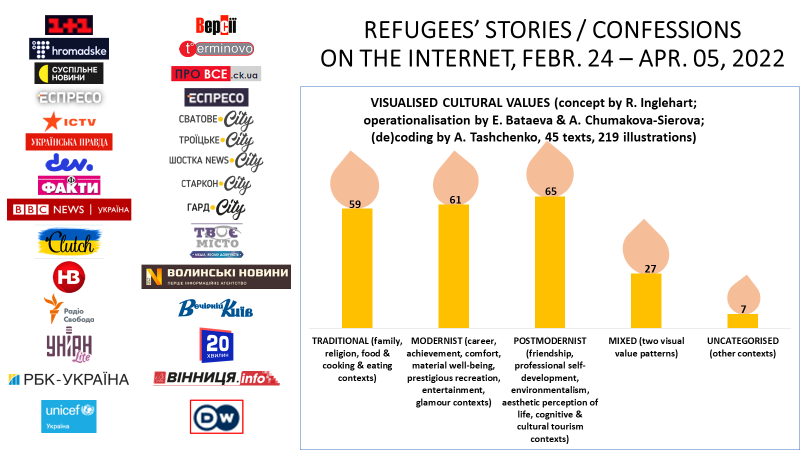

Secondly, I collected all Google-available illustrated stories / confessions by refugees from Ukraine that had appeared on online media from the morning of February 24 till the evening of April 5. The exploration of those stories and confessions published by a wider range of media (twenty-nine state and private outlets, including both all-Ukrainian, and local Ukrainian, and international ones available in Ukraine) delivered a complicated value portrayal of wartime refugees from Ukraine. While telling stories and confessing about their lives, refugees didn’t live exclusively in the present moment, and the media didn’t tend to present them as people without past and desire to return to normal daily life (at least partly) too. The visualised cultural values reflected both the diversity of the media or their communication policies and the differences in the experiences of refugees, in their cultural codes.

Image 4: Media list, and the ratio of the visualised values on these media

The visualised cultural values were, so to speak, aligned: the texts were filled with photos of both families, and breakfasts/dinners, and apartments, and household items, and worried acquaintances, and friendly strangers, and emotions on human faces, and influential patrons of refugees, and ordinary companions… Also, a forced movement remained a travel in its nature, so, it contributed to the media presentation of refugees’ current life via photos of the environment with other nature, landscapes, architecture, street arts. Despite the fear, anxiety and sorrow, the refugees remained doing a lot of sightseeing and exploring – photographing the process of movement, stations, transport, new people, unusual cultural conditions.

Image 5: Selection of photos from twenty-nine media images

The most painful images to perceive were the ones with hidden storytelling about breaking the most basic value – the value of human life (images of parts of the obviously lifeless human body, individual corpses, mass-killed people). The same main meaning was also repeated through bloody stylised illustrations devoted to Russian propaganda, international ‘business on blood’ (collaborating with Russia and paying to its structures despite the war and sanctions), violent Russification and made by the Ukrainian state Center for Countering Disinformation (broadcasted via Viber). The moral relevance of such images remains debatable, and physical security context still needs its visual operationalisation, as well as new ones having had secondary relevance in peaceful time – e.g., the context of political participation.

Image 6: Selection of photos from twenty-nine media and CCD images

Beyond the wartime images

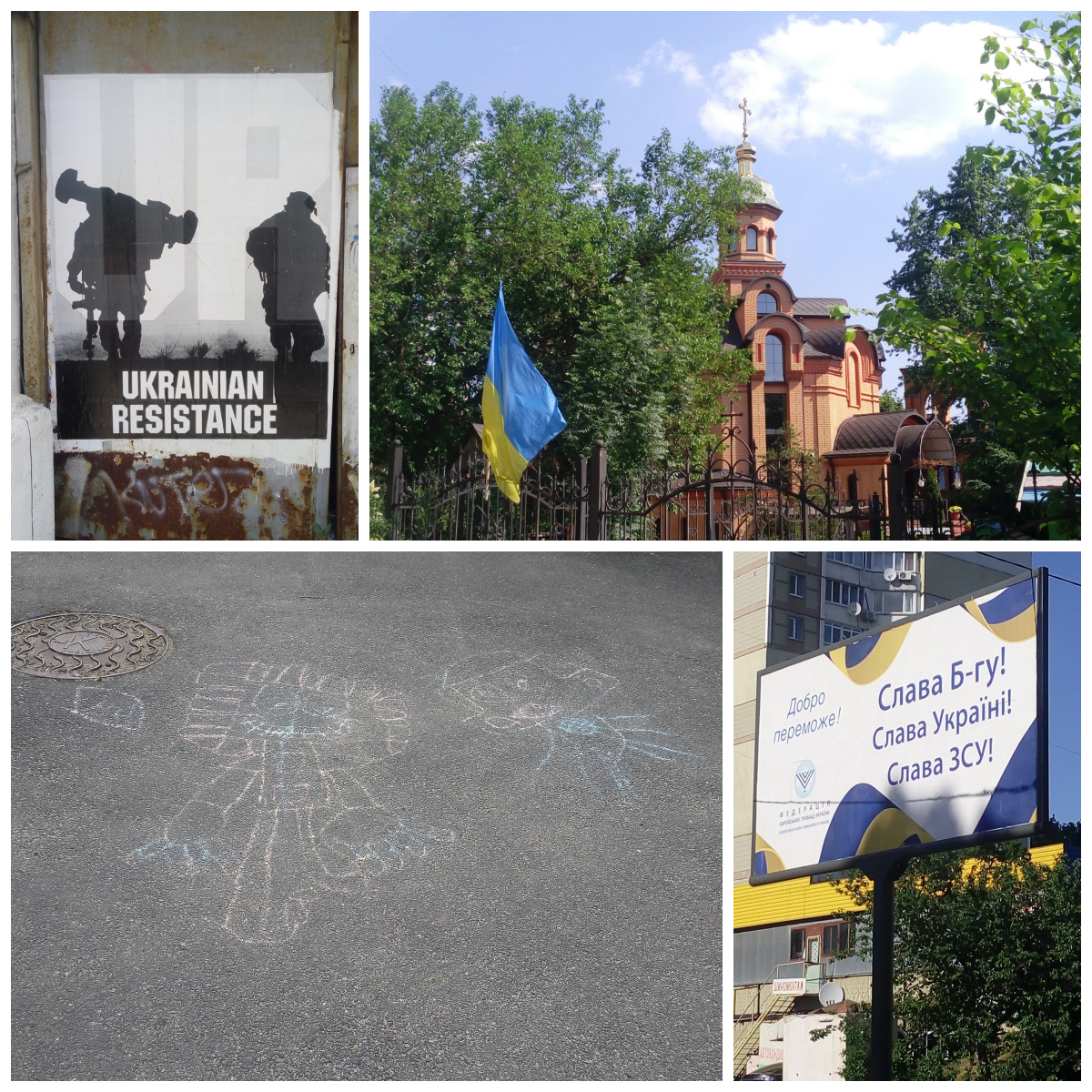

I believe that both the ‘demonstrable values’ and ‘visualised values’ issues will outlive the current war and state of uncertainty. Even now, it is obvious that its basic idea naturally intertwines with the already developed studies of visualisations, because values are centered around certain tacit conventions (as you could see above, there are reasons to assume the presence of media local conventions), hiding behind usage of pop-culture’s representations, and managing daily understandings of economic improvement. Visual images saturated with cultural values go beyond media and science – they are there when the church incorporates the national flag into its appearance, when new posters are pasted along the streets, and even when children’s chalk drawings return to the asphalt instead of broken glass from bombed houses. Therefore, the visual analysis of cultural values can hardly be devalued even in the so-called ‘post-value world’.

Image 7: Photocollage with Kyiv photos made by the author

This blog piece was prepared within the ‘Global media narratives of the Russia-Ukraine war’ project curated by Dr Eva Polonska-Kimunguyi. I am deeply thankful to her for non-stop supporting, mentoring, and reviewing, and to our co-researchers, especially to Petra Radic, Ella Startt, and Zichen Hu (Jess) for a very fruitful and warm-hearted collaboration and discussion.

This blog piece was prepared within the ‘Global media narratives of the Russia-Ukraine war’ project curated by Dr Eva Polonska-Kimunguyi. I am deeply thankful to her for non-stop supporting, mentoring, and reviewing, and to our co-researchers, especially to Petra Radic, Ella Startt, and Zichen Hu (Jess) for a very fruitful and warm-hearted collaboration and discussion.

This article reflects the views of the author and not those of the Media@LSE blog nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.