Drawing on his ongoing research, Dr. Toussaint Nothias, Visiting Fellow in the LSE’s Media and Communication department and research director of the Digital Civil Society Lab at Stanford University, calls for more accountability and research over Facebook initiatives to increase connectivity across the Global South. In this post, he explains how the visual properties of Facebook’s so called “free” Internet access help us understand the ever-growing influence of Big Tech over journalism worldwide.

Drawing on his ongoing research, Dr. Toussaint Nothias, Visiting Fellow in the LSE’s Media and Communication department and research director of the Digital Civil Society Lab at Stanford University, calls for more accountability and research over Facebook initiatives to increase connectivity across the Global South. In this post, he explains how the visual properties of Facebook’s so called “free” Internet access help us understand the ever-growing influence of Big Tech over journalism worldwide.

How much do you pay for your internet connection? If you live in Europe or North America, you will probably think first about your broadband connection. And you will think about a number like €40 euros or $50 dollars. If you live somewhere on the African continent, you will likely think first about your mobile phone data plan. And you would probably answer: “I pay too much!”

Consider these two facts: most of the world’s population accesses the Internet, not through laptops but through mobile phones. In addition, the costs of connectivity remain sharply unequal globally. For instance, take the price of 1GB of mobile data. According to the Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI), 1GB of mobile data in the US equals 0.7% of the average person’s monthly income. On average, across Africa in 2020, 1GB of mobile data represents 5.8% of the average person’s monthly income (A4AI). There are also sharp inequalities within the African continent. In Ghana, for instance, 1 GB of mobile data equals 1.4% of the average monthly income, while in the Central African Republic, it reaches 24%: watch one episode of Bridgerton, and you will have lost a quarter of your monthly salary.

There are thus striking differences and inequalities in the costs of connectivity. But current scholarly debates on social media, democracy, and journalism rarely consider these simple facts. The emerging literature often treats connectivity as something static, homogenous, and evident – even despite a well-established literature on the digital divide. This shortcoming reflects an American and Euro-centric bias that is as unsurprising as unfortunate.

In contrast – and building on the work of digital rights activists (such as Nanjala Nyabola) and global communication scholars (including Payal Arora and Wendy Willems) – I believe we need to pay greater attention to the many different ways people across the world connect to the Internet. I will focus here on one instance: the so-called “free” Internet access provided by Facebook.

This type of access, also known as zero-rating, is globally widespread, particularly across the Global South. Facebook keeps quiet about the actual extent of the program’s reach. In prior research, I found that Facebook’s Free Basics had expanded to at least 32 countries in Africa by 2019. According to internal documents revealed by the Wall Street Journal (2022), the program helped the company gain around 10 million new users each month in the second half of 2021 alone. Shockingly, the Wall Street Journal revealed that due to technical issues, some users were in fact charged for using Facebook’s “free” version. According to the internal documents reviewed by the journalists, people in impoverished countries who had been promised free access ended up paying collectively about $7.8 million per month for the period July 2020 to 2021.

For the past four years, I have been researching the expansion of Facebook’s various free access initiatives, particularly across the African continent. I have been tracing their history, growth, and evolution. And, at the moment, I am researching their impact on access to information and news pluralism.

In this post, I want to reflect on three peculiar visual features of this free access, and why they matter for journalism. I will focus on how this free access 1) visually constructs silences; 2) moderates the form of journalism, not just its content; and 3) creates a singular visual aesthetic. These three visual features, I will argue, all have important implications for journalism globally. Before I turn to these, let me provide some quick background on free basics and zero-rating.

Background

In 2010, Facebook launched Facebook Zero. Facebook Zero provided users with a stripped-down, text-only version of the Facebook mobile website. Users did not incur data costs to access this service. People did not have to pay any money to access the service. This process is called zero-rating, and it gave the name to the project – Facebook Zero.

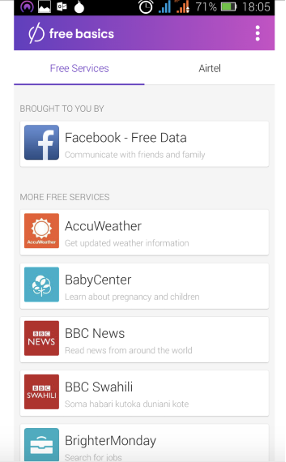

Over the years, Facebook experimented with other zero-rated initiatives. In 2013, Facebook launched Internet.org. Here, users could access not just the Facebook website but a selection of text-only websites. The selection was arbitrarily made by Facebook. It included sites like Baby Center, Accuweather, and news organizations like the BBC, Voice of America, and Deutsche Welle, who partnered with Facebook to be included on Internet.org. In addition, Facebook also onboarded local news organizations to localize the offerings in various countries.

These notably included Rappler, the news organization headed by 2021 Nobel Peace Prize Maria Ressa. While today Ressa is largely known as a fervent advocate against the power of Big Tech – and in particular, Facebook – Rappler was one of Facebook’s partners when it launched the free app in the Philippines. At the time, she even appeared in a Facebook promotional video where she explained that the free platform “gives us a way to talk to people who wouldn’t normally have access to Rappler.”

In 2015, following pushback from activists in India, Facebook rebranded Internet.org. “Free Basics” was born. Rather than including only a list of sites selected by Facebook, Free Basics was more open. Any developer could have their website on the Free Basics platform – if they made their site compatible with Facebook’s technical requirements.

In 2020, Facebook created yet another version called Discover. This time, Facebook promised that users could access any website for free. How is that possible? Like previous initiatives, Discover removes content that consumes a lot of data – things like high-quality images and pictures, videos, and animations. In a way, this Free Access is a visuals-lite access.

Visuals-lite but not visuals-free

This free access may be visuals-lite; but it is not visuals-free. Instead, it has peculiar visual features, and these features open pressing questions for journalism across the world in our age of digital dependencies.

First, because Free Basics removes data-heavy content, it calls on us to attend to the silences – what is not shown and what is left out. This point, of course, is not new. Indeed, one of the most powerful tools to understand the ideological load of media representations is to look at what is not being shown and ask why. In a similar spirit, Mike Annany recently described silence as an important, yet undervalued and understudied, form of participation in contemporary online life.

But what is at stake for journalism on this data-lite Internet is not just any silence. It is what is being actively removed and redacted through a seemingly neutral technological choice. As we strive to understand the significance of news visuals, we need to attend to different types of silences and ask: what is being redacted, why, and by whom?

This leads me to my second point. Removing data-heavy content – including high-quality visuals – is not simply a technical choice. Instead, we should understand this as what scholars Lucy Pei, Benedict Olgado and Roderic Crooks call “form moderation”.

In their recent study of the Discover App in the Philippines (2021), they found that this data redaction process creates a radically unequal rendering of the Internet. Most websites looked like an array of gray boxes stating, “Use data to see photos”. For instance, Yahoo – which was surprisingly classified in the app as a “News source” – was unusable in free mode. Users had to pay for data to see the image needed for the Captcha. In contrast, the Facebook website, of course, kept its features intact. Unsurprisingly, these willful omissions and choices reinforce the dominance of Facebook, including for news consumption.

In the past decade, the question of online content moderation and its relevance to journalism has become a core focus of journalism studies and political communication scholarship. But what is at stake here is a different type of moderation, “form moderation.” “Form” here refers to the appearance and arrangement of content. In this free access, the appearance of content is disrupted. And just like content moderation matters for public discourse and journalism, so does form moderation.

In Burma, for instance, Free Basics included one local news portal, a news site called 7DayDaily. In 2018, researchers Daniel O’Maley and Amba Kak interviewed the general manager of 7Day Daily. He explained that Facebook had approached other local news outlets to include them on Free Basics. However, these other news organizations did not have the technical expertise to maintain a data-lite version of their site. Here, form moderation creates a technical barrier with implications for media pluralism; it uplifts the visibility of larger news organizations with more digital capacity, while it pushes out smaller, local news organizations.

In Zambia, in contrast, Wendy Willems found that Zambian online news sites would post the entire content of their articles on Facebook pages, rather than including hyperlinks to their own website. This way, she explains, users would not incur data charges. In this case, form moderation results in news organizations gradually shifting their online presence over to the Facebook platform altogether.

Lastly, let us consider this landing page for Free Basics (Figure 1). This is the main page that users encounter in Kenya – even before they log in on Facebook.

Figure 1 – Free Basics, Kenya. Source Global Voices (2017).

There are no visuals as we most often understand them – no pictures or images. Yet this page has a particular visual aesthetic. Consider the color, the logo, and the font. These, taken together with the prominent placement of Facebook, create a specific visual aesthetic. Here, Free Basics resembles a Facebook-style browser or portal. In many parts of the world, Facebook has thus become almost synonymous with the entire Internet – in part because of its free access initiatives. An often cited 2015 survey of Nigerian Internet users found that 65% of them agreed with the statement that Facebook is the Internet.

Included in this walled-garden are the logos of the news organizations that had to create a data-lite version of their website to be featured on Free Basics. Aesthetically, these news organizations become framed and surrounded by Facebook’s homogenizing visual brand and style – even before people log in on Facebook.

This is yet another component of the ever-growing power that big tech has over journalism. This power is not only power over metrics and the circulation and moderation of content. It also takes the form of partnerships with news organizations, funding for journalism via grants and donations, moderating the “form” of journalism, and even here – by subsuming the online presence of news organizations under Facebook’s homogenizing visual aesthetic.

These three lessons – accounting for silences, form moderation, and visuals beyond images – may emerge from geographical contexts that the literature on social media, democracy and journalism largely sees as peripheral. Yet, I would argue that these lessons are globally relevant. They point to understudied yet crucial ways social media companies influence public discourse and journalism. And as Big Tech companies expand their reach to new layers of the Internet, such as undersea fiber-optic cables and data centers, we will certainly need more research and greater accountability over Big Tech’s influence on journalism across the Global South.

Note: An earlier version of this post was presented at the 72nd International Communication Association Conference in Paris as part of a panel on “Journalism, Technology and the Visual Production of Meaning” organized by Giorgia Aiello, Chris Anderson, Hellen Kennedy, and Ariel Chen

This article reflects the views of the author and not those of the Media@LSE blog nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash