Nathalie Van Raemdonck, a PhD researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) in Media and Communication science, explains the implications of the lack of friction in how content spreads on Instagram through the platform’s core features.

Nathalie Van Raemdonck, a PhD researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) in Media and Communication science, explains the implications of the lack of friction in how content spreads on Instagram through the platform’s core features.

Instagram used to be known as a place where users could display their ‘authentic self’ – or where they would enhance such a self with several filters. Self-expression on Instagram has however long gone beyond image sharing. The platform is now filled with personal as well as professional content creators who primarily share memes, text-posts and infographics. While most are benign or even social justice oriented, there are also a significant number of accounts spreading factually incorrect or hateful content.

In this piece I explain how Instagram’s architecture and affordances facilitate the circulation and acceptance of hateful content and misinformation, as well as shaping what I call the ‘normative friction’ that can slow such a spread. This focus stems from a recently published article in which a colleague and asked ourselves, how can users shape other people’s behavior given the digital spaces they inhabit? With this post I show what this looks like in practice on a platform like Instagram.

The way in which users can intervene in what they deem to be socially unacceptable has important repercussions for the question of how friction can be added on Instagram to slow the spread of hate speech and misinformation. Accuracy nudges have been proven to be an interesting avenue in reducing the spread of misinformation. What room is there for other users to make such nudges in the form of a ‘normative intervention’?

(illustration of normative interventions against disinformation by Toby Morris and Siouxie Wiles)

(illustration of normative interventions against disinformation by Toby Morris and Siouxie Wiles)

Spread on Instagram

First, we need to have a look at how content spreads on Instagram in order to understand visibility on the platform, and where users could potentially make such normative interventions.

Content can go viral on Instagram both organically and/or algorithmically. Because of the possibilities to share Instagram posts in Stories, a post can spread far and wide throughout the platform without much algorithmic recommendation.

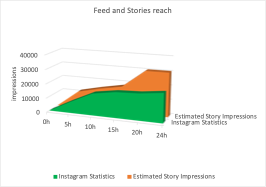

Content spread on Instagram is understudied due to a lack of digital method tools. This spread is even misrepresented in the official statistics Instagram shares with users. I illustrate this with a post on my own Instagram account @anti_conspiracy_memewars, which was set up during the COVID-19 pandemic as a personal project to debunk and prebunk false information with memes. For 24 hours I logged the official impressions statistics that Instagram provides, as well as the 191 times this post was shared in Stories (with the caveat that this could only be logged for public account shares). The amount in green below are the official statistics, while the amount in orange below shows how many people most probably saw the post in other users’ Stories.

Fig. 1: Post impressions in green, impressions from Stories in orange

Fig. 1: Post impressions in green, impressions from Stories in orange

The estimated Story impressions was calculated by counting the number of followers of all 191 accounts that shared the post in their Stories, and taking a percentage of those followers based on a recent marketing survey by Social Insider that found accounts with less than 5000 followers reach 10% of followers, and more than 5000 followers only reach 5%. This is thus a conservative estimation how many eyeballs this post reached organically. The views of this particular post peter out after 10h according to Instagram, while the views from Story shares keep going for a few more hours.

Regardless of whether Instagram’s statistics are accurate, we can conclude that posts have the potential to reach as many or even more people organically rather than algorithmically. This is significant for friction efforts that focus on algorithmic de-amplification of contentious content, as it it is less effective when posts are shared in many Stories. With 500 million daily active users of the Stories feature a huge amount of content gets shared in this way. Stories’ ephemerality (content disappears after 24h) makes it even more difficult to estimate the impact of such organic spreads.

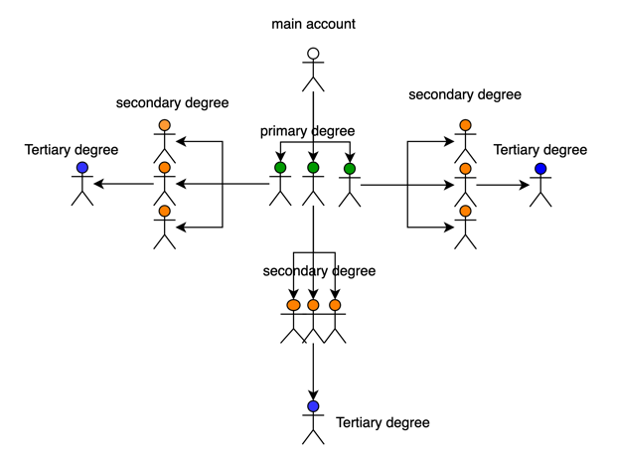

As for its behavioral impact, content can enter networks organically that are several degrees removed from the original account. I illustrate this by showing how far the previously mentioned post became removed from my network by logging whether a follower or non-follower shared this post in their Stories. We split up the orange bar in Figure 1 into views from a secondary and tertiary degree, and illustrate what this looks like in a network.

Fig 2a. Impressions from a secondary degree in orange, impressions from a tertiary degree in blue.

Fig 2b. Illustration of the primary, secondary and tertiary degrees in the network of an account whose post is shared.

Organic amplification can thus make content spread throughout the entire information ecosystem of the platform. There, such content can potentially transform norms and push the needle of what is acceptable content, if there is no normative friction. This sometimes deliberate tactic is described by Joshua Citarella as ‘slow red-pilling’. Such a norm-challenging content spread is of course not unique to Instagram: it is similar to how content spreads on platforms like Twitter and Facebook. It is however commonly believed that Instagram users merely influence their own followers, while in fact, depending on their settings, posts can actually go far and wide beyond the primary network of followers. It is key to investigate how such tactics can be countered with normative interventions. For this we look at some key characteristics of Instagram’s architecture, which provide the affordance of what we coined “interactability” and “interventionability”.

Normative interventions on Instagram

Normative interventions are ways in which users can signal to other users that they think a piece of content breaches a certain social norm. Whether such an intervention is effective at enforcing a norm depends on several factors – the tone, the general consensus on the norm they are trying to enforce, the social identity and reputation of users. Yet such an intervention will have little to no impact if it is not even seen by other users.

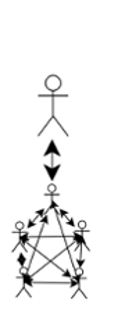

This is exactly where the interactability of Instagram matters. We conceptualized this as ways in which users can interact with each other through the platform’s two main features: Posts and Stories.

Posts are what we call a ‘connected one-to-many’ interaction. Central to this interaction is that people seeing an Instagram post are able to interact with the sender of the post and with each other. Whatever comment or contribution they make about this post – which could include a normative intervention – is seen both by the sender and other receivers of this post. In this way users can signal to others that they feel this post breaches a norm, and potentially even influence the behavior of the sender when more users agree on this normative intervention. Commenting is usually the only ‘interventionability’ users have, which we conceptualised as ways in which users can do some sort of normative intervention. Since commenting can also be turned off or removed by the account owner using their own interventionability, one of the only ways of adding friction left for users is to report to the platform. These then become the sole actor to intervene on potentially harmful content by de-amplifying or removing it.

We call Stories an ‘isolated one-to-many interaction’ because users don’t even have interventionability in the form of public comment. When content is shared in Stories, it is broadcast to all followers, but receivers can only interact with the sender. If a follower responds, that comment lands directly in the sender’s personal inbox, turning it into a one-to-one conversation. This means users cannot signal to other receivers when they feel a Story is breaching a social norm: they can only disagree with the sender in a one-on-one interaction.

A huge number of users might only come across a post when it is shared in a Story, where they will be isolated from the discourse of other receivers of that post. This can make a post travel through the platform without friction or much visible discourse. Receivers still have the possibility to visit the original post in its connected one-to-many setting and comment there or see discourse in that location, but this will not affect the Post in the Story and will remain unseen by receivers who do not want to spend another click on visiting the original post. Consequently, normative interventions against a post shared in Stories will only impact the sender, not other receivers, and can fall on deaf ears if the original sender refuses to engage in the one-to-one conversation.

The implications of these insights about Instagram’s architectures is that it can be harder for users to add normative friction to the spread of hateful or deceptive content. Given how content spreads as much or even more organically than algorithmically, users play an important part in halting such a spread.

Some research has shown that social corrections done in a more intimate setting do have more positive effects as people feel less called out in public. This interactability can thus also have positive consequences for normative conflicts as it can lead to a more heart-to-heart conversation about the responsibility of sharing contentious content. Accuracy nudges can feel very hostile when they’re done in public. As Alice Marwick argues, social norm enforcement can also disproportionately affect minorities, since society-wide norms usually privilege whiteness, heteronormativity, maleness and so forth, thus keep existing power balances intact.

There is thus no right and wrong platform architecture to halt the spread of hate speech and misinformation without unintended consequences. It is however important to be aware of Instagram’s particular affordances and how they shape normative corrections differently. While it can allow users who are challenging oppressive norms to have a more frictionless experience, it could potential also lead to a more frictionless spread of harmful content. Policy solutions that aim to include users more and share the responsibility of platform governance should take into account the degree of agency that users realistically have to self-govern their online spaces.

This article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Solen Feyissa on Unsplash