As debate continues around wider regulation of artificial intelligence in the US and globally, Olivia Otts, a candidate for LSE’s MSc in Media and Communications Governance, looks at how AI is being used in US political campaigns to create synthetic content and how this could be regulated.

As debate continues around wider regulation of artificial intelligence in the US and globally, Olivia Otts, a candidate for LSE’s MSc in Media and Communications Governance, looks at how AI is being used in US political campaigns to create synthetic content and how this could be regulated.

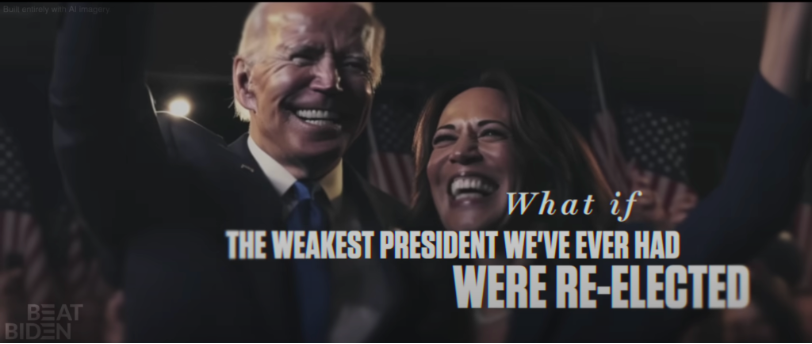

In April, the US Republican Party’s GOP YouTube account posted a short video, Beat Biden, to present what the party sees as the ramifications of President Joe Biden’s potential 2024 re-election. The video interspersed AI-generated imagery of a hypothetical re-election alongside a bombing of Taiwan, a surging migrant crisis, decaying financial buildings, and a crime-induced shutdown of San Francisco. However, the video protected itself from accusations of fabrication with a clear hypothetical – “What if the weakest president we’ve ever had were re-elected?”

“Beat Biden” YouTube video (GOP)

“Beat Biden” YouTube video (GOP)

Background

The potential consequences of the unregulated use of synthetic media in political campaigns have led some in Washington to propose solutions, but not without controversy. This past summer, it was reported that the US Federal Election Commission (FEC) had “begun a process to potentially regulate AI-generated deepfakes in political ads ahead of the 2024 election”. However, it was argued by one Republican Commissioner that this proposal “would wrongly chill expression that’s protected under the First Amendment.” The balance between safeguarding the information ecosystem and stifling free speech is now being hotly contested.

Would regulating this type of synthetic media in political advertising constitute a slippery slope into the regulatory overreach of the right to free speech? It could be argued that posting a synthetic representation of an individual is a form of artistic licence, akin to a painted portrait. It could also be argued – at a stretch – that the usage of generated content in political campaigns is a cost-saving measure, allowing candidates with less funding to gain a spot in a costly political attention economy. What is clear is that the use of synthetic video, photo, and audio content in political advertising has led to complex ethical and regulatory debates which deserve further critical attention.

Skirting disclosure

The AP recently reported that “Google will soon require that political ads using artificial intelligence be accompanied by a prominent disclosure if imagery or sounds have been synthetically altered”. The article clarifies that this ban extends to “Google’s own platforms, particularly YouTube”. In the example above, the GOP’s usage of synthetic media was to visualise a hypothetical future rather than to directly misrepresent reality. The ad itself appears to be compliant, given that it disclosed synthetic content. However, what “prominent disclosure” entails – in Google’s view – is yet to be seen. Given that this video is live and in line with YouTube’s Community Standards, how can it be understood in the wider context of synthetic political campaigning? Does danger come from the potential to use segments of such videos for direct disinformation, or is the core risk the gradual normalisation of synthetic media in politics itself?

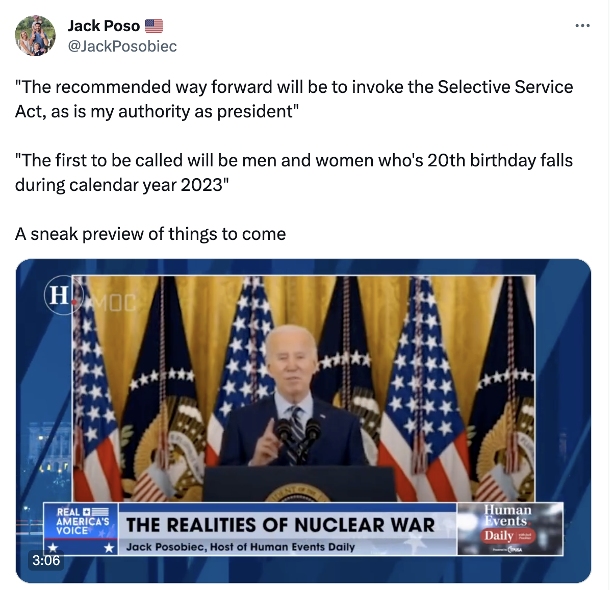

One might argue that this video is part of another slippery slope into the acceptance of more malign uses of synthetic media on the digital campaign trail. Take, for example, Donald Trump’s own Truth Social repost earlier this year showing a representation of him kneeling in prayer – with no disclosure of the fact that it was synthetic. This pose, beyond playing into Christian nationalist discourses, doesn’t seem to attempt any strategic misrepresentations of reality. In short, it should be seen as protected speech. However, the former president’s willingness to share a synthetic image without context on his own social network points to a wider gap in accountability for niche platforms such as Truth Social. Even if mainstream networks’ synthetic media regulations are airtight, networks with lax requirements for synthetic content disclosure may become breeding grounds for more epistemically damaging uses of synthetic media. Note a case in which Jack Posobiec, a right-wing television presenter, retweeted an AI-generated video of Biden invoking the Selective Service Act in preparation for nuclear conflict.

Retweet and caption by @JackPosobiec

Retweet and caption by @JackPosobiec

Although the original poster did note that the video was AI generated, Posobiec did not disclose this. One might counter that the spelling errors in the second line would be enough for most viewers to disregard this content as false. However, this may not be a reliable assumption. The video lost vital context when spread across the platform, emerging after its repost as a sloppily misleading screencap of an invocation of the Selective Service Act, as seen above. This contextual transformation exemplifies the challenge that deepfakes pose for platforms’ notice-and-takedown requirements. Who should be liable when harms arise from the de-contextualisation of synthetic content – the original poster, the platform, or the reposter themself?

Note that if the above examples were presented for satirical purposes they likely would – and arguably should – be treated differently by most platforms. These exceptions are important to understand, but frequently misunderstood. Discussing the potential criminalisation of deepfake content this year, one Reddit commenter expressed they were “concerned that the senate has seemingly removed exceptions for AI generated imagery that are parody, satire, commentary, criticism or have political or news value.” Another commenter rebuffed: “(…) Unless the constitution is amended or the SCOTUS decides we no longer have freedom of expression, that kind of image will remain protected.” Who is right here? In some ways neither, and in some ways both. A lawyer who works for the Republican Party, Caleb Burns, suggested to BloombergLaw that “privacy law, copyright law, and defamation claims” may form “potential litigious solutions” to synthetic campaign ads. It is important to note the obvious here – combating synthetic political content with regulatory and/or legal instruments is not always appropriate.

Creative liberty?

For example, synthetic political satire or commentary can arguably have artistic and expressive merit. When created to represent “celebrities or other public figures”, parodies are also of course protected by the First Amendment, as held in Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell. “Reanimating historical figures” is another use-case that recent pieces have noted to be protected by the First Amendment. Robert Weissman, president of the advocacy group Public Citizen, recently argued that “acknowledging deepfakes are fraud” is a solution to some First Amendment concerns, noting that “while false speech is protected, fraud is not”. However, it would be hard to argue, for example, that reanimating a past president for a historical series is fraudulent. It would also be challenging to assert that a “deepfaked” meme of any political leader in a clearly satirical context is always fraudulent. If this deepfake showed a politician stating their own home address, privacy law could be a potential solution. If the deepfake showed a politician spewing vitriol in a reasonably believable context, defamation law could potentially be applied.

Regulating deepfakes

There are multiple areas of existing legislation and platform policy that may apply to synthetic media, such as those related to copyright and defamation. There are also emerging state-level proposals and legislation in this area – primarily aimed at curbing deepfake image abuse. In spite of recent progress, it is clear that any attempt to regulate deepfakes in political campaigning will encounter several overlapping complications. First, regulators must consider how to align synthetic media policy with First Amendment considerations – especially in cases of satire and creative use. Second, they must define and justify exceptions, and critically examine the free speech implications of the risk of regulatory overreach. A solid place to begin would be to consider the grey areas of this space – between innovative technological adaptation and abuse, between satire and harmful defamation, and between the protection of democracy and the freedom to create. When considering the usage of synthetic media in political campaigns, the protection of the democratic process would ideally be in conceptual parity with the right to freedom of expression. With regulatory proposals in this space still nascent, now is the time for concerted discussion on how to construct that delicate balance.

This post represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Tabrez Syed on Unsplash