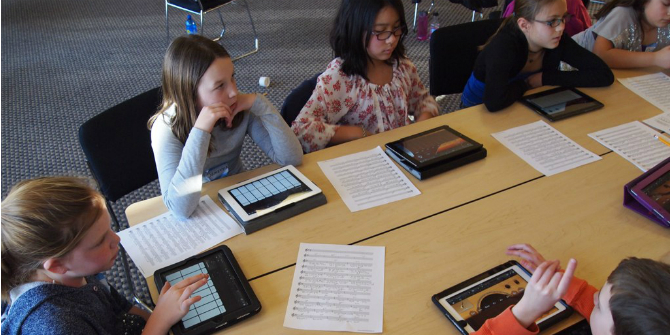

Credit: D. Li, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Credit: D. Li, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Guest blogger Diane Levine looks at the delicate and often sensitive balance between prying or protection, and offers some useful tips for how parents and their teenagers can journey together in the online world. Diane has worked in government research on technology in education, and recently completed her PhD in the Centre for Education Studies at the University of Warwick. She is a mother of two.

Guest blogger Diane Levine looks at the delicate and often sensitive balance between prying or protection, and offers some useful tips for how parents and their teenagers can journey together in the online world. Diane has worked in government research on technology in education, and recently completed her PhD in the Centre for Education Studies at the University of Warwick. She is a mother of two.

According to a recent BBC News story, there is a debate ‘raging’ in South Korea about how much control parents should have over their children’s browsing –young people under the age of 19 must install an app that enables their parents to block sites and see their children’s activity online. If the app is not installed, the phone will not work.

Do we demonise teenagers?

Two things struck me about this news story. First, it shows some of the tensions often reported by parents of teenagers, and teenagers themselves. Paternalism versus autonomy, privacy versus protection. Second, we often see this sort of language about teenagers in the media. Ever since the famous quote from Aristotle about their ‘fickle, changeable and violent’ natures, teenagers seem to get bad press.

As parents we sometimes experience that adolescents can be challenging. We blame their hormones, but we rarely stop to think how difficult it might be for them to manage the big physiological changes happening during this life phase.

Finding a way to talk

I recently completed a project looking at the technology use of girls aged between 9 and 17. I focused on girls because we know girls and boys navigate puberty in quite different ways, both structurally in the brain and in psychological terms. The girls I worked with were from a range of backgrounds, but were not those who we are most worried about societally – like researcher danah boyd, I wanted to know about the technological practices of ‘ordinary’ girls.

I focused on the interplay between technology and ‘social cognition’, a psychological term for how we understand ourselves within the different social worlds that we inhabit. I used Valsiner’s Zone Theory and life course perspectives to understand my participants’ activities, and found that young women have strong and highly personalised perspectives relating to technology use.

For example, one 12-year-old self-defined gamer shared her critical perspectives of available games, and contextualised her gaming behaviours in the context of her extra-curricular dancing, French, gymnastics and violin lessons. A quiet nine-year-old talked about how e-readers did not appeal to her, finding physical books a more immersive experience.

In the best tradition of research with teenagers, my participants and I busted two common myths.

Myth 1: Technology overrides impulse control, robbing teenagers of their sense of choice

What we really found

Young people exercise choice on a moment-by-moment basis in every moment of their technology-mediated lives. Sometimes these choices are based on their prior experiences, personality, brain structure and impulses. Daniel Kahneman calls these System 1 choices. Sometimes they are System 2 choices, which are much more conscious and deliberate. Most of my participants spoke about the conscious choices they made in choosing to participate or not in social media communities.

Some didn’t participate because of because of in-depth e-safety training at school. According to one 12-year-old, “… everyone has done the internet safety lesson.” For others it was because of a wish to remain private. For example, one 16-year-old maintained tight privacy settings and a very small group of friends on Facebook, including her mother, excluding anyone she did not interact with regularly at school, and she used a generic photo rather than a personal one.

A third group chose their online spaces on the basis of their interests. One 17-year-old was uninterested in social media except for Tumblr, which was “opening up a new, more visual community.”

What you can try

The most empowering thing a teen can do is to learn to talk about how they understand themselves and their choices. They need to make their choices explicit. This will make them less vulnerable to temptations they might encounter when using technology. Parents can help their children manage their technological futures.

Questions and activities to do together with a teen

- Write down 10 words or sentences to describe yourself. Ask your teen to do the same. Talk about what these statements might mean about you as people.

- Talk about a person who has a big influence on your teen’s life. Does your teen interact with that person online? Now have the same conversation about a group of people. What role do individuals, groups and systems such as schools play in the ways teenagers engage with technology?

- Sit down with your teen during a time when they are using technology. Talk about what your teen understands about the motivations of other users, and also of the technology designers. What sorts of behaviours do these motivations lead to? For example, discuss the role of rewards in online gaming. Does your teen think that rewards make it more likely to become addicted to a game?

Myth 2: Teenagers don’t want adults poking into their online worlds

What we really found

As Leslie Haddon recently showed, adult interest in teenagers’ lives isn’t always resented; it can sometimes be welcomed. The teens in my project do not live in another world – their many worlds intersect with ours in ways that can be quite carefully chosen and managed. For example, one British participant wrote fan fiction with an online friend in the US. She was an enthusiastic and committed writer, and found herself struggling to maintain distinctions between the online fan fiction that she was creating and her day-to-day experiences. She turned to her mother:

I think I’d sort of subconsciously known for a long time that this was what was happening. But I hadn’t really cared. And then somewhere along the line I thought, ‘This is getting kind of serious. I’d better do something before it goes any further.’ And that’s when I talked to Mum. I can’t remember what she did. She kind of talked to me and helped me decipher what was real, and what wasn’t real. I think it was mainly the talking that did help. (17-year-old)

What you can try

Find a place where you and your teen are both comfortable. Begin to make a shared language to talk about your child’s increasing independence, their fears, the changes in their bodies, the influence their peers and technology-mediated media has on their lives. Self-awareness will give them a greater feeling of personal control as they develop positive relationships and understanding of others. This will help them to remain safe online.

Questions and activities to do together with a teen

- Ask your teen to keep a short diary noting changes in their body and feelings. Do they notice anything interesting? If you are a mother and have a regular cycle, make your own diary.

- Keep a family diary of how much technology you all use over a weekend. Which technologies are you using, and why? What sorts of family interactions happen around technology?

- Get into the habit of visiting sites together with your teen, make recommendations to each other, send each other links to funny things you find online, follow each other on Twitter.

These ideas should help parents and teenagers to begin to talk about the ways in which technology relates to their developing social cognition. Talking works – enjoy your journey!