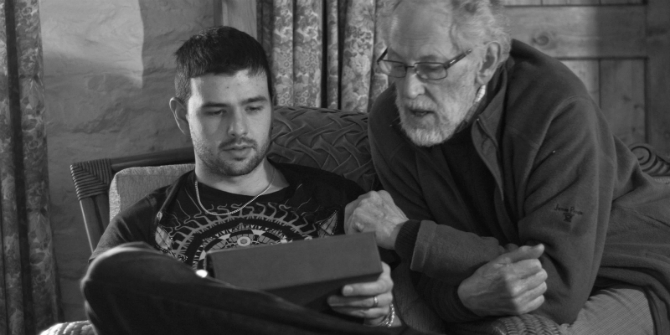

Vikki Katz has studied the children of immigrants as they ‘broker’ for their parents. She outlines some lessons to be learned from her research, throwing into question the apparent native/immigrant divide. Vikki is an Associate Professor at Rutgers University’s School of Communication and Information, and Senior Research Scientist at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. Her work focuses on how immigrant parents and their children address communication challenges related to their social incorporation in the United States. [Header image credit: S. Evans, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Vikki Katz has studied the children of immigrants as they ‘broker’ for their parents. She outlines some lessons to be learned from her research, throwing into question the apparent native/immigrant divide. Vikki is an Associate Professor at Rutgers University’s School of Communication and Information, and Senior Research Scientist at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. Her work focuses on how immigrant parents and their children address communication challenges related to their social incorporation in the United States. [Header image credit: S. Evans, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Calling children digital natives, in contrast to their digital immigrant parents, has become a popular way to explain family tensions around technology. People use the native/immigrant distinction to explain why children use technology more fluently than adults – which, in turn, raises concerns that parents have no control over what their children do with technology.

But what happens when parents are actual immigrants, and their children are native-born? For the past 10 years, I’ve studied children of immigrants who, as the main English speakers in their families, ‘broker’ for their parents. In Kids in the Middle and Children Being Seen and Heard, I showed how children broker parents’ interactions with English-speaking teachers, healthcare and social services providers, and customers in family-owned businesses, as well as their parents’ connections to media devices and media content.

Below, I draw some lessons from my research on children’s media brokering, based on a four-year ethnography for Kids in the Middle, a small interview study of children’s online search behaviours, 334 interviews with Mexican-heritage parents and children in three US states, and a just-completed, nationally representative survey of 1,191 low-income parents about family technology use. Findings across these studies shed serious doubt on the deep intergenerational rifts that the digital native/immigrant divide takes for granted.

The importance of children’s contribution

Children’s media brokering is often collaborative and has positive outcomes for parents and children alike, because they can make serious contributions to what their families can access, both on- and offline. As more resources go digital, children’s brokering broadens the range of information and services their families can access. Their efforts are often integral to their families finding a new doctor, an after-school programme for a sibling, or a job opportunity.

Children also help in more mundane ways. One interviewed mother said:

[My kids] will help me, if I want to post something or create something … there’s an app that we use where you can make a professional flyer, forward it to your email, and you can print it. So they help me do that. And last night my son helped me put an ad in Craigslist.

Whether they are helping parents with potentially life-altering activities like finding a new job, or simply increasing the range of tasks parents can accomplish online, what they do is important to their families.

Successful brokering

When children broker, they are not acting alone. While they appear to be taking the lead when they locate online resources or explain a sibling’s symptoms to a doctor, children being active doesn’t mean parents are passive. It also doesn’t mean that parents have lost control, or that their children have seized it. In fact, in every study, children’s brokering is most likely to be successful (from the family’s perspective) when parents and children work together.

Children may contribute their greater fluency in English and their facility with new technology, but they broker best when parents are there to actively contribute their adult perspectives on family needs. Collaborative engagement with technology provides powerful opportunities for parents and children to exchange expert and learner roles, and for both to learn new skills and information in the process.

The difficulties of online brokering

That being said, children find brokering online more difficult than other brokering activities. This past year, my colleagues and I conducted a study specifically on children’s online search and brokering behaviours. It became clear that they find brokering online more taxing than brokering other media content.

Fernanda (age 14) described online brokering by saying:

It takes forever, ‘cause when I translate what [my mom] wants, she’s like, ‘Oh, since you’re online, check out something [else] for me’ … [and then] we’re there for like a good hour … because she wants to keep branching out somewhere.

Amelia (age 13) agreed, saying:

I prefer [brokering paper documents] than internet for the same reason … online, you search for something and you get something else that you weren’t searching for, so then it messes you up.

These experiences reflect two important points: first, the ability to seamlessly navigate vast amounts of content, which is usually considered a benefit of seeking information online, can be cognitively overloading for child brokers. They found self-contained tasks, like brokering a letter, easier to control. Second, being the intermediary for family connectivity can be challenging for children, even as it enables important connections

A family affair

And finally, children’s brokering is not an ‘immigrant thing’ – it’s a family thing. If you or anyone you know has had a child teach you how to download an app or send a text message, you have relied on a child’s media brokering skills. While children whose immigrant parents have limited English proficiency, formal education and/or experience with technology, and engage in more media brokering than other children, these activities are not unique.

In fact, preliminary findings from our recent national survey of lower-income parents revealed that White, Black and English-speaking Hispanic parents in the US also rely on children’s media brokering, especially if they have less formal schooling and household income. Our findings reinforce that for families with limited resources, children are likely to be important conduits to the opportunities that new technologies can offer.

The challenge of brokering

In sum, the digital immigrant/native divide does not hold up in my research on immigrant and low-income families in the US. Intergenerational cooperation around technology use is common, and provides potential learning gains for parents and children alike, although this is not to say that these interactions are always easy.

Children still find online brokering challenging, which is why it is so important for these young people to have trusted support outside of their families to turn to for help. Providing help not only means giving technical assistance; it also means recognising and respecting what children do for, and with, their parents as a considerable family strength.