It used to be ‘Big Brother is watching you’, and we worried about CCTV, but today’s children are being watched in their ‘real’ lives as in their virtual lives. So what right do they have to privacy? Wendy M. Grossman takes a closer look at this issue, with some startling findings. Wendy writes about the border wars between cyberspace and real life. She is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award and she has released a number of books, articles, and music. [Header image credit: Brandi, CC BY-ND 2.0]

It used to be ‘Big Brother is watching you’, and we worried about CCTV, but today’s children are being watched in their ‘real’ lives as in their virtual lives. So what right do they have to privacy? Wendy M. Grossman takes a closer look at this issue, with some startling findings. Wendy writes about the border wars between cyberspace and real life. She is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award and she has released a number of books, articles, and music. [Header image credit: Brandi, CC BY-ND 2.0]

“But she has no data”, Katie Bond pleads in the 2010 documentary Erasing David, trying to convince her husband, David, to sign the form required by the very good nursery they’ve found for their three-year-old daughter. David balks – the form gives the school permission to do anything it likes with their daughter’s data. The result was his film about surveillance and the ‘database state’.

Spying on students

The choice the Bonds faced is one that few parents even notice. On 1 December 2015, the digital rights advocacy group, Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), filed a complaint with the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) alleging that Google is collecting and mining schoolchildren’s personal information as part of its ‘Google for Education’ programme. If their allegations are correct, Google is violating the promises it made in (after some delay) signing up to the Student Privacy Pledge, now endorsed by President Obama, and signed by 200 companies. The basis for this complaint was unearthed while EFF was researching its broader Spying on Students campaign.

A business model endorsed by schools

A case study EFF has posted to illustrate its complaint makes it clear that there are two prongs to this problem. One is Google’s business model and privacy practices, the substance of the FTC complaint; the other is the response schools make to such complaints. It is the latter that has been most debated in the UK, particularly with respect to school fingerprinting in libraries and cafeterias.

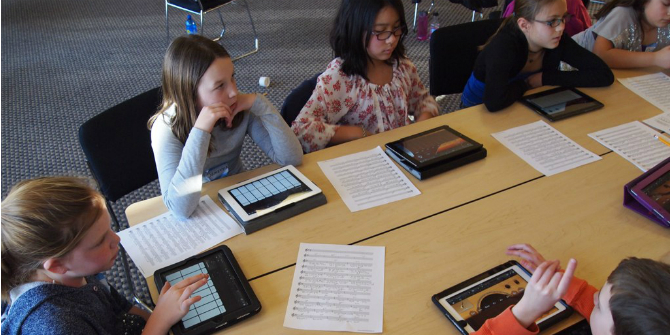

Parental protests about the practice began in the mid-2000s and continued until 2012, when the Department of Education ruled that under the Protection of Freedoms Act, schools must get parental permission before collecting biometrics from pupils. The California school district in EFF’s case study has decided to issue a particular technology – Chromebooks and Google Apps for Education (GAFE) – without requesting parental consent for aspects such as syncing the students’ data to the cloud, and opening the required Google account.

When challenged on privacy issues, the school refused to consider alternatives beyond an initial period. This is key: privacy is a social compact as well as an individual right, and refusing to engage with these issues has as widespread consequences as to whether or not children are vaccinated. At the individual level, in requiring students to use Chromebooks, the school is doing the technological equivalent of deciding that its vending machines will stock only Coca-Cola products and students may not drink anything else.

Other UK complaints, such as those highlighted by former teacher Terri Dowty, who led the campaigning group Action for the Rights of Children for many years, have focused more on government databases. With such initiatives in mind, in 2008, Dowty commented that children had already lost the rights that the rest of us were struggling to retain.

Unsanctioned data mining

Returning to EFF and Google, the difficulty EFF highlights is that children, like adults, use their tablets and laptops for more than just school assignments. They browse websites, read blogs, hang out on Facebook or Foursquare, upload pictures, play games, both social and individual, listen to music and watch videos. Much of this activity takes place on other services owned by Google, such as its search engine, maps, cloud storage, and YouTube, but they do not, as EFF notes, fall within GAFE categories, and therefore lie outside the privacy protections Google has promised for GAFE.

So EFF’s objection is not that Google uses data collected as children do their homework to personalise their learning device and guide their education. It is that whenever a child is signed in using their educational account – whether that’s on the school Chromebook, a parent’s laptop or a personal mobile phone – Google is collecting, retaining and mining all the data from their use of all those other services, and connecting it to the child’s education profile. You might respond (as Google probably will) that children could set up a separate account for personal use and use that instead, but this is a level of digital hygiene at which even adults frequently fail.

This is why any electronic device is fundamentally different from a textbook: a physical book cannot monitor which pages you read, which paragraphs you highlight, or which other books you consult for explanations and then retain that information for reuse – but Amazon does. A physical textbook does not know who your friends are or where you like to go after school – but Google (or Facebook, Apple or Microsoft) does.

Consequences for privacy and the ability to reinvent oneself

Apple and Microsoft have other sources of revenue, but the entire business model of Google and Facebook revolves around mining data. Whatever favourable terms these companies provide to education, they are businesses whose interests in the children who use their technology is primarily, if not purely, financial.

This doesn’t mean that all use of their services should be summarily rejected, but it does mean that their use should be thought through carefully. Parents are right to be concerned about the consequences for their children’s privacy, and their concerns should be taken seriously.

EFF’s concerns about Google play into a broader trend: today’s children are monitored with an intensity that was never applied to any of today’s adults. They are watched by CCTV and profiled by technology companies, and the minutiae of their school lives are recorded. Today’s adults were able to reinvent themselves when they matured. Today’s children won’t be able to do so.