What kind of digital content is available for children in Turkey? How are Turkish parents deciding rules about screen time and tablet use? What do children use tablets for? Burcu Izci and colleagues compare young children’s tablet use in Turkey and the US, and also the extent to which parents limit children’s access to tablet devices. Burcu Izci and Yasin Yalcin are PhD candidates at Florida State University (USA); Tugba Bahcekapili is a PhD candidate at the Middle East Technical University (Turkey) and a research assistant at the Karadeniz Technical University (Turkey); and Dr Ithel Jones is a professor at Florida State University. [Header image credit: B. Flickinger, CC BY 2.0_07]

What kind of digital content is available for children in Turkey? How are Turkish parents deciding rules about screen time and tablet use? What do children use tablets for? Burcu Izci and colleagues compare young children’s tablet use in Turkey and the US, and also the extent to which parents limit children’s access to tablet devices. Burcu Izci and Yasin Yalcin are PhD candidates at Florida State University (USA); Tugba Bahcekapili is a PhD candidate at the Middle East Technical University (Turkey) and a research assistant at the Karadeniz Technical University (Turkey); and Dr Ithel Jones is a professor at Florida State University. [Header image credit: B. Flickinger, CC BY 2.0_07]

Due to their affordability and easy-to-use touch screens, tablets are now widely available worldwide. In this blog post we focus on the Turkish context, comparing it to the US. A majority of Turkish children (age 6 or younger) (52.3%) spend an hour or less with tablet devices on week days, with this amount of time increasing at the weekend (to 54.2% for at least one hour), which is similar to children in the US. However, Turkish parents say that finding age-appropriate, high-quality digital content for their children is difficult, and they are also concerned about their children’s safety in a digital environment.

Children’s tablet use

As Dafna Lemish explains, children’s media use occurs mostly within the home and in the family context. According to Wartella and colleagues, parents establish the media environment at home, and their individual choices (such as putting a TV in a child’s bedroom or using devices to keep a child busy) determine the children’s access to media and the amount of screen time they are allowed.

We looked at Turkish and American children’s tablet use as well as their parents’ decisions about children’s access to a tablet device at home, with parents filling out an online survey specifically designed to understand various decisions regarding children’s tablet use (such as letting children use a tablet at home, planning to buy a tablet in the future or avoiding children’s access to the device altogether). Overall, 401 parents participated (270 from Turkey and 131 from the US). Most of the Turkish parents were educated (69.2% with at least a college degree) and were from middle or high socioeconomic statuses.

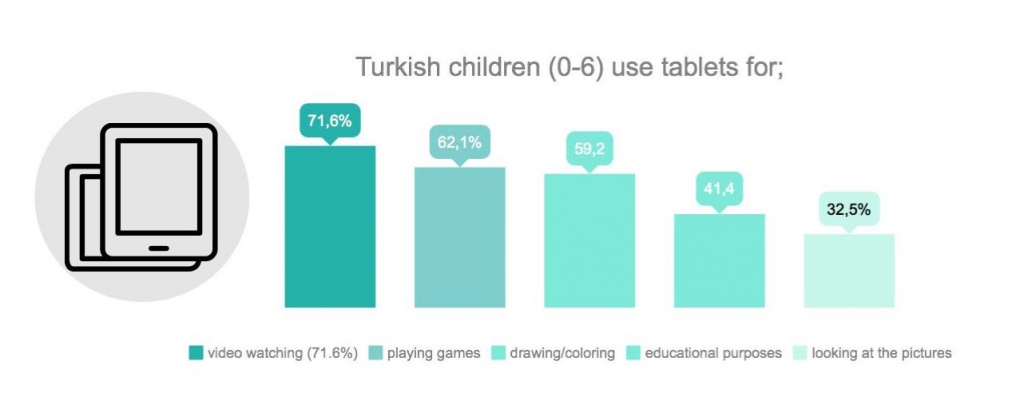

Of the children surveyed, 62.7% use the tablets alone and 56.8% use the tablet with their parent. Most use tablets for watching videos, playing games and drawing/colouring, as well as for educational purposes.

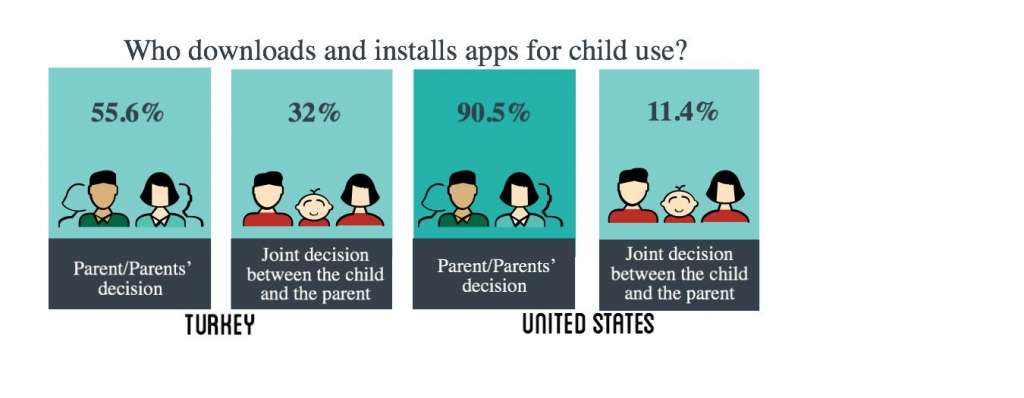

Turkish parents generally let their children decide on an application themselves before they download it. Although more than half of the Turkish parents download apps themselves, a third of families listen to their children and decide with them. This compares to more than 90% of the American parents downloading apps for their children, and only 11% including children in the decision-making process. This difference may be related to cultural perspectives about children’s digital media use, as well as differing parenting strategies. Particular media organisations and centres in the US (such as Common Sense Media, Fred Rogers Center, Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop) may also influence American parents’ awareness about children’s media, helping them find high-quality digital content.

High-quality digital content and applications

Today’s children or ‘digital natives’ have grown up with touch screens and digital media, with touch screens slowly taking over the place of TV, and even children’s toys, books and crayons. NAEYC and the Fred Rogers Center suggest that technology and media offer opportunities to extend children’s learning in much the same way as books, building blocks and art materials. In October 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics modified the screen media guidelines for children, and recommended parents use high-quality educational media by engaging in conversations with their children. Similar to American parents, most Turkish families prefer free apps for their children (83.6%), and are comfortable when children use tablets for educational purposes, or when asking for help. They still worry about the amount of time that children spend on tablets as well as using devices unobserved. Turkish parents also share their worries about children being exposed to inappropriate content, and are willing to pay for apps that come without adverts.

As Lisa Guernsey believes, content (apps, games and TV shows that parents let the children watch or play), context (such as talking with children about what they watch, ensuring their media use doesn’t affect their play or conversations) and child (being aware of the needs of the individual child) should be considered when deciding children’s media use. YouTube (Kids), PBS Kids, Netflix and Sesame Workshop were popular platforms for American children. Similarly, YouTube was popular among Turkish children in addition to various game and educational applications. Parents also reported that their children use both Turkish and English applications.

Some Turkish parents were unable to share the names of their children’s favourite apps. This shows us that either these applications were commercial and designed by unknown companies, or that the parents have limited knowledge about the digital content used by their children. In Turkey, media platforms such as TRT Cocuk and Digital Medya ve Cocuk are making great efforts to educate parents and support children’s learning in this digital age. TRT Cocuk is a Turkish national station that broadcasts cartoons and educational programs for children. Its website includes filter options for families to choose content by filtering the children’s age, expected gains, topic and content type. Digital Medya ve Cocuk belongs to a private university in Turkey, and its team translates media research conducted with children as well as sharing recent news with parents and educators.

A digital future for children in Turkey

As reported in an EU Kids Online report, from 2010 to 2015 the age of first internet access in Turkey dropped from 5 to 2. With the increased popularity of touch screens, further research is needed to understand more about young children’s digital media use in Turkey, as well as the nature of parent–child shared learning experiences around these devices.

The media industry and researchers need to listen to Turkish parents. Conducting empirical studies with families and children, designing age-appropriate, high-quality digital content and sharing expert reviews with families and educators will support Turkish children’s learning from touch screens and digital media in the future.

Our survey was adapted from the TAP study, Common Sense Media’s 2013 report and the work of Plowman and colleagues.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science