The UK Chief Medical Officer has just released a report on screen use and the mental health and wellbeing of children. This post by Sonia Livingstone examines new research which has shown that the length of screen time for children is not as harmful as first thought, and calls for a more balanced approach. Sonia Livingstone is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

The UK Chief Medical Officer has just released a report on screen use and the mental health and wellbeing of children. This post by Sonia Livingstone examines new research which has shown that the length of screen time for children is not as harmful as first thought, and calls for a more balanced approach. Sonia Livingstone is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

Oft-repeated advice to parents to limit their children’s screen time changed in recent weeks:

“We’ve got the screen time debate all wrong. Let’s fix it.” (Wired, 20/12/18)

“Parents can relax about too much screen time.” (Mail Online, 14/1/19)

“Worry less about children’s screen use, parents told.” (BBC, 4/1/19)

“The Kids (Who Use Tech) Seem to Be All Right.” (Scientific American, 15/1/19)

As anyone watching this debate knows, dissatisfaction with official advice has been mounting for some time. The American Academy of Pediatrics, originator of the famous 2×2 rules (no screens under 2 years, no more than 2 hours/day thereafter), finally conceded that in the digital age, such advice is impossible to follow. New screen time rules in Australia and elsewhere have been critiqued. And while screen time rules are themselves exploited by the booming market in surveillance apps which capitalise on parental anxiety, there has been outrage in discovering that tech entrepreneurs protect their children from their own inventions.

But why the sudden change in advice to parents? In January 2019, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health published a systematic review of reviews in the British Medical Journal by Neza Stiglic and Russell Viner which concluded, notwithstanding a series of concerns, that “evidence to guide policy on safe CYP screentime exposure is limited.”

At the same time, Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski published a paper in Nature Human Behaviour showing through statistical analysis of multiple large-scale data sets that any relation between digital technology use and adolescent well-being is, by comparison with almost any other factor you can think of (eating potatoes is the factor that appealed to the headline writers), “too small to warrant policy change.”

As with the lit match held to dry straw, the sudden change in headlines, and these new reports, contributed to a tipping point in the mounting problems with the screen time debate. These problems fall into three categories:

- Scientific problems of evidence. Any effects linking screen time and negative outcomes are tiny (and dwarfed by other factors, such as sleep). Potentially confounding factors (especially socio-economic circumstances) are rarely controlled for. Studies tend to be cross-sectional, preventing causal conclusions. Measures are strongest for physical health (notably, obesity – though here they make the problematic assumption that screen use is sedentary) and weak or non-existent for mental health outcomes. And so on.

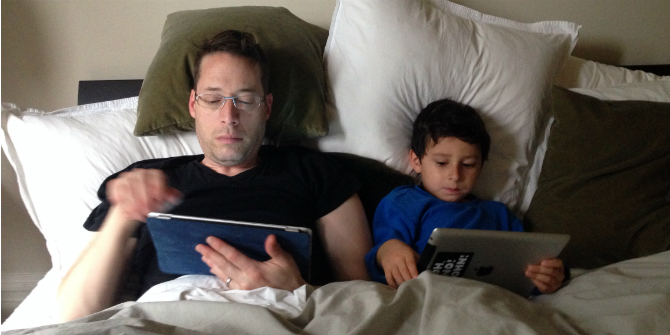

- Practical problems of implementation. In the digital age, parents find limiting screen time impossible because they are exhausted and screens are everywhere, because limiting screen time causes family conflict and undermines digital media learning, and because for all kinds of families – diasporic families with relatives abroad, families whose children have special educational needs, families keen to gain new digital skills for future jobs – screen media offer important benefits.

- Conceptual problems. We can no longer frame screen time as optional or avoidable. Digital technologies increasingly provide the infrastructure for all dimensions of society, for better and for worse. It’s time to shift from policing screen time to weighing screen use in terms of the value of its content, context and connections. Parents are not the police and nor are media-loving children criminals or media an unalloyed threat to civilised society, as we discuss in our forthcoming book. Moreover, in the digital age, children’s rights to information, expression, play and communication are at stake.

But the new narrative does not mean that screen worries are over. For example, a large scale study scanning the brains of US kids recently warned of problems possibly linked to screens. Concern over hidden persuasive techniques which “hijack” children’s minds is also rising (although this too has been critiqued). Evidence in favour of mobile phone bans in schools is widely discussed. Evidence of a host of specific risks is also rising although, as ever, this shows that what matters is not so much time spent and more content, context and connections; hence the need for contextual judgements not blanket rules. For such reasons, pro-technology calls to embrace the positives are as simplistic and misguided as screen time restrictions.

What parents need is not generic or simplistic rules (I’d go so far as to say that they only expect rules focused on time because that’s what they’ve become used to) but constructive guidance that helps them realise the advantages of the digital age as well as avoid its harms. For this, the public debate could usefully pay more attention to those reports that do weigh the evidence and reach balanced conclusions. The House of Lords’ Growing up with the internet is one such. One hopes that the Science and Technology Committee’s inquiry into the impact of social media and screen-use on young people’s health will be another (though their task is far from easy). Also helpful is input from bodies such as the Science Media Centre, which seek to counter panicky media reporting. The outcome, surely, must be a multi-stakeholder approach which tackles the pros and cons of the digital age with the seriousness that it deserves.

This means we need a change in research practice too. For instance, while conscientiously conducted, Stiglic and Viner’s study remains firmly within the medical model. They acknowledge the problems with the evidence, including that most research reviewed is out of date, being concerned with television and with little to say regarding current digital devices. But they seem unconcerned at excluding from consideration any evidence for the educational, social or civic benefits of screen use. And equally they do not critique the many studies they review from failing to measure adequately the socio-economic circumstances of their participants, even though it is well known that social disadvantage is linked both to greater screen use and to negative life outcomes. While policy and practice needs a multistakeholder approach, research surely needs a multidisciplinary one – as begun here.

Meanwhile, as a matter of urgency, it’s time to improve messaging to parents, who are now very confused. This should come via the mass media, and by advising those who work with parents. Jackie Marsh has done this in relation to the potential educational benefits of technology for pre-schoolers. Relatedly, I have tried to reach health visitors. In the US, Common Sense Media, and in the UK, The Children’s Media Foundation have a great role to play here. And now the Chief Medical Officer has added her voice. Parents deserve a more thoughtful debate, that both engages and empowers them. Let’s hope they get it.

Notes

This post originally appeared on The Children’s Media Foundation website and it has been reposted here with permission.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.