With growing concerns over children’s online privacy and the commercial uses of their data, it is vital that children’s understandings of the digital environment, their digital skills and their capacity to consent are taken into account in designing services, regulation and policy. Sonia Livingstone, Mariya Stoilova, and Rishita Nandagiri’s research project Children’s Data and Privacy Online set out to ask children directly, which was not a straightforward task. Here, they briefly explain their approach to focus groups, a key part of the project’s overall methodology (for more, see here). You can read about some findings in another post, and more are added to the project website each month. [Header image credit: L Plougmann Creative Commons]

With growing concerns over children’s online privacy and the commercial uses of their data, it is vital that children’s understandings of the digital environment, their digital skills and their capacity to consent are taken into account in designing services, regulation and policy. Sonia Livingstone, Mariya Stoilova, and Rishita Nandagiri’s research project Children’s Data and Privacy Online set out to ask children directly, which was not a straightforward task. Here, they briefly explain their approach to focus groups, a key part of the project’s overall methodology (for more, see here). You can read about some findings in another post, and more are added to the project website each month. [Header image credit: L Plougmann Creative Commons]

Focus groups allow children’s voices and experiences to be expressed in a way that is meaningful to them, and permit children to act as agents in shaping their digital rights, civic participation, and need for support. Drawing on the relevant research literature, our aim was to use real-life scenarios and exemplar digital experiences to facilitate the focus group discussions and to ensure that children are clearly focused on the opportunities, risks, and practical dilemmas posed by the online environment.

Our initial pilot research demonstrated some challenges of researching children’s privacy online – children found it hard to discuss institutional and commercial privacy, as well as data profiling as they seemed to have substantial gaps in their understanding of these areas. They also did not see their online activities as data or as sharing personal information online. This made it hard to establish how important privacy was for them and what digital skills they had.

Our initial pilot research demonstrated some challenges of researching children’s privacy online – children found it hard to discuss institutional and commercial privacy, as well as data profiling as they seemed to have substantial gaps in their understanding of these areas. They also did not see their online activities as data or as sharing personal information online. This made it hard to establish how important privacy was for them and what digital skills they had.

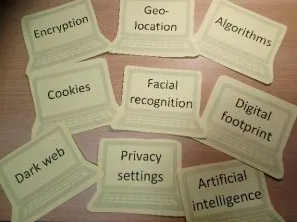

To address this, the team took a step-by-step approach – starting with the unprompted perceptions of privacy and children’s practices (for example, in relation to selecting apps, checking age restrictions, reading terms and conditions, changing privacy settings, getting advice about new apps from others) and a quick test of their familiarity with relevant terminology (e.g. cookies, privacy settings, algorithms, facial recognition). Then moving on to more complex areas, such as types of data they share and with whom, gradually building the landscape of children’s online behaviour and enabling discussion of less thought-of areas such as data harvesting and profiling.

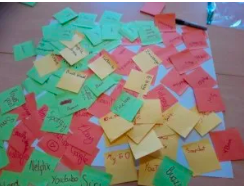

An activity that worked really well as an introduction was asking children about the apps and websites they used over the past week – this produced very quickly a comprehensive picture of their recent activities and the platforms they engage with. The examples of the apps they use then offered an opportunity to ask about their practices in a more contextualised and familiar setting, rather than talking about the internet more generally, which children found harder.

An activity that worked really well as an introduction was asking children about the apps and websites they used over the past week – this produced very quickly a comprehensive picture of their recent activities and the platforms they engage with. The examples of the apps they use then offered an opportunity to ask about their practices in a more contextualised and familiar setting, rather than talking about the internet more generally, which children found harder.

To discover children’s familiarity with privacy-related terminology, we asked, simply,  “Have you heard this word? Can you tell me what it means?” This proved very effective in enabling children to talk about their experiences on their own terms before we gradually introduced more complex privacy issues, such as data sharing.

“Have you heard this word? Can you tell me what it means?” This proved very effective in enabling children to talk about their experiences on their own terms before we gradually introduced more complex privacy issues, such as data sharing.

Another challenge was to help children describe what they share online and their understanding of how additional information might be collected in the background by the apps and used to create a digital profile. The initial idea to ask children to brainstorm about all the data they might have shared, with prompts from the team, was not very effective.

The team therefore re-structured the activities, making them more visual and interactive. This enabled children to engage better with the different dimensions of privacy online and relate their experiences to the discussed issues.

Children were given four sharing options – share with online contacts (interpersonal privacy), share with my school, GP, future employer (institutional privacy), share with companies (commercial privacy), and keep to myself (desire not to share something). After discussion with the UnBias project, we identified 13 types of data that might be shared digitally and reduced these to the nine most relevant categories: personal information, biometric data, preferences, internet searches, location, social networks, school records, health, and confidential information (for more, see here).

Children were given four sharing options – share with online contacts (interpersonal privacy), share with my school, GP, future employer (institutional privacy), share with companies (commercial privacy), and keep to myself (desire not to share something). After discussion with the UnBias project, we identified 13 types of data that might be shared digitally and reduced these to the nine most relevant categories: personal information, biometric data, preferences, internet searches, location, social networks, school records, health, and confidential information (for more, see here).

Children were asked to say whether they share each type of data with anyone, why they might share it and what the implications might be. This worked really well as it allowed children to relate the examples to the applications they use and to some practical situations (e.g. sharing information about your address with a delivery app).

Interestingly, this exercise demonstrated that children often choose ‘keep to myself’ spontaneously but, as the discussion progressed, they acknowledged that they are sometimes asked for this data and feel obliged to provide it.

Still, thinking about the possible future implications remained a challenge. The discussion often diverted to general internet safety with children reciting familiar messages about ‘stranger danger’ and password sharing but failing to grapple with how their data might become available online and how it might be used for unintended purposes. A lot of prompting was used to elicit greater details about this.

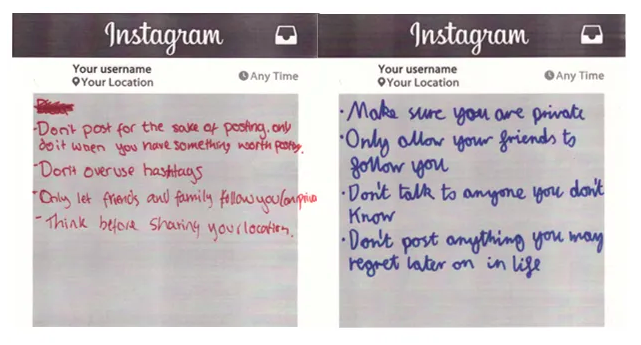

To facilitate children’s thinking about the future and about child development, we designed an activity ‘Advice to a younger sibling’ where children write a message to an imaginary younger sibling telling them what they need to learn about privacy online. This exercise worked well but children still struggled to express what effective strategies might be.

Finally, we felt that some questions might have remained unanswered, and we gave children the opportunity to ask any questions they still had, and make suggestions for changes in the future. This worked well and we will be using this input in the design of the online toolkit for children we’re now developing.

This post originally appeared on the Media Policy Project blog and has been reposted here with permission.

This article represents the views of the authors, and not the position of the Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.