In the second of four posts presenting findings from the Makerspaces in the early years (MakEY) final report, Sonia Livingstone, Alicia Blum-Ross, and Paige Mustain investigate how educators view parents roles within these spaces, and how the physical set up of the spaces encourage parents’ interaction.

In the second of four posts presenting findings from the Makerspaces in the early years (MakEY) final report, Sonia Livingstone, Alicia Blum-Ross, and Paige Mustain investigate how educators view parents roles within these spaces, and how the physical set up of the spaces encourage parents’ interaction.

In our previous post wrapping up our findings from the MakEY project, we considered the different roles that parents played within makerspaces. We discussed the variety of roles parents adopt, inspired partly by studies by Barron et al. (2009) and Brough et al (in a forthcoming volume on Connected Learning) who determined that parents take on distinct roles as ‘learning’ partners in helping children develop technological skills. In our MakEY project we also found that instead of a contrast between engaged versus disengaged parents, we found that their roles were more complex and often adopted through deliberate decision-making. This was not always apparent to the educators who shared their (sometimes critical) perspectives on parents’ roles with us.

Educators’ views of parents

In addition to observing and talking to parents, we were also interested in how the educators who worked in these spaces viewed parents, and also whether and how the parents were invited in by the physical set up of the makerspaces.

Although they strove to be positive, we found educators were sometimes critical of parents. They either worried about the parents that were “uninvolved” in their children’s activities (babysitting, previous post) or those that were so involved that they ‘took over’ what the child was doing. One experienced educator who worked in a more diverse setting (socio-economically and ethnically) explained:

I see a lot of different parenting styles… sometimes there are parents who are very encouraging. Sometimes I do get some parents who are literally on their phone the entire time and not paying attention to what their child is doing… sometimes [parents] actually do the activities for them… So it’s a mixture of all of those things, sometimes with the same parent within a few hours.

Given that she referenced parents from a multitude of different backgrounds it is fair to say that there are parents of all stripes occupying each of these roles, as above. Yet educators serving more privileged parents also explained how:

I think that the protective parents don’t want their kids to fail. But that’s part of what this space is – a safe place to fail; the design process is failing, and testing and improving.

In this sense the ethos of the makerspace itself – privileging failure and therefore iteration (the tag-line of the makerspace at one makerspace we visited was ‘Think, Make, Try’) – was at odds with the demands of some parents who asked (in the words of an educator) “how can I make sure my kid has the right answer?”

Physical set up of makerspaces

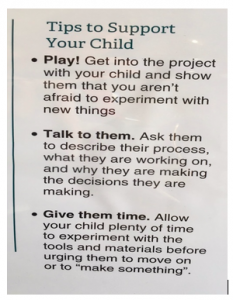

In order to work with parents whom they perceived as sometimes too pushy, but sometimes too uninvolved, educators tried a variety of different techniques to physically invite parents in.

For example, each of the makerspaces had greeters who stood at the door and often gave the parents instructions to get their child started. This was a subtle way to let parents know they were expected to stay and participate with their children.

The way each makerspace was set up physically impacted the level of parental involvement. For instance, one museum had tables and chairs that were very low with other activities taking place on cushioned mats on the floor. This made it difficult for some parents to join comfortably since they had to physically crouch over children to help them with the objects.

Another makerspace took a completely different tack – having only waist height tables with no chairs at all so that visitors stood around the tables (this meant caregivers could be more involved but that everyone spent less time overall in the activity). At the third museum the makerspace was set up more like a classroom with tables grouped together. This made it easier for caregivers to sit with children for longer periods of time, especially grandparents with limited mobility (of the three makerspaces this is where we saw this most frequently), but required a large amount of space tucked out of the main exhibit.

It was apparent that educators held varying views of parents in makerspaces. There was a tendency to be critical, with educators expressing concern over parents being too hands-off or too involved. As we covered in our previous post, the roles parents occupied were fluid and much more complex than this. An important takeaway is how educators’ views of parents’ roles influenced the physical arrangements of the makerspaces which had an impact on how involved or uninvolved the parents seemed to be. When the space was more inviting with comfortable seating for parents we saw more engaging with their children in the activities. This points to the importance of matching makerspaces’ physical arrangements with the goals of the makerspace.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.