Encountering cyberhate is becoming a prevalent experience for children in Europe – at least one in five children aged 11-17 have witnessed such content. In some countries, the proportion is much higher. Marie Bedrošová – a researcher from the Masaryk University in Brno (Czech Republic) summarises the findings of a new EU Kids Online report investigating the experiences of over 9,000 children from 10 European countries who were surveyed about their encounters with hateful content and messages.

Encountering cyberhate is becoming a prevalent experience for children in Europe – at least one in five children aged 11-17 have witnessed such content. In some countries, the proportion is much higher. Marie Bedrošová – a researcher from the Masaryk University in Brno (Czech Republic) summarises the findings of a new EU Kids Online report investigating the experiences of over 9,000 children from 10 European countries who were surveyed about their encounters with hateful content and messages.

Which children are exposed to cyberhate?

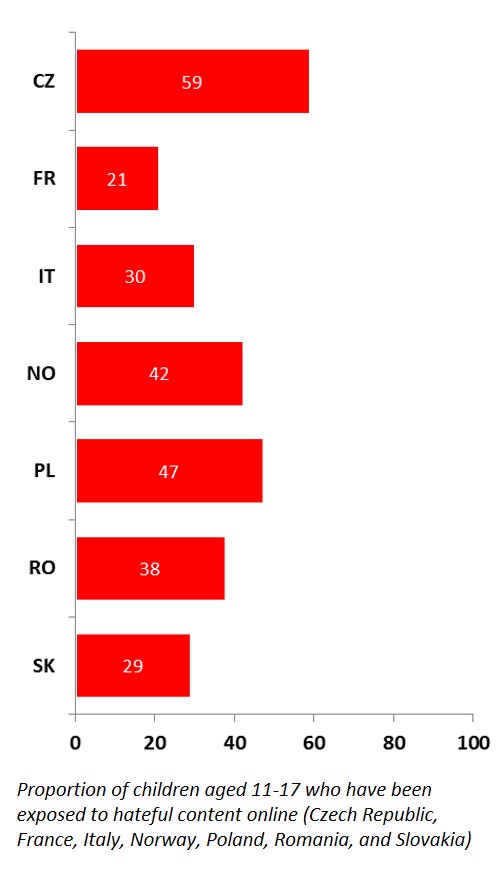

While cyberhate can happen in closed hate groups, it increasingly appears in mainstream online communication on social media, news websites, and discussion fora where children can easily encounter it while using the internet. Our findings show that such online experiences are not rare – between 21% (France) and 59% (Czech Republic) of children aged 11-17 have been exposed to hateful content online.

While cyberhate can happen in closed hate groups, it increasingly appears in mainstream online communication on social media, news websites, and discussion fora where children can easily encounter it while using the internet. Our findings show that such online experiences are not rare – between 21% (France) and 59% (Czech Republic) of children aged 11-17 have been exposed to hateful content online.

Cyberhate is hate speech expressed on the internet through technologies, such as computers and mobile phones. It attempts to justify intolerance and discrimination, attacking people based on their group characteristics, such as ethnicity, religion, or sexuality. In radical cases, cyberhate can become online extremism. Across all countries we studied, older children are more likely to encounter cyberhate content but we still need to find out why the exposure to cyberhate varies so much across the countries. Moreover, some children encounter such content daily or almost daily – between 1% (Italy, Slovakia) and 6% (Czech Republic).

Which children are targeted by cyberhate?

The number of children who are targeted by cyberhate (receive hateful and degrading messages aimed at them or their communities) varies between 3% (Italy) and 13% (Poland). This is suggested in the new report published by the EU Kids Online based on findings from 9,459 children aged 11-17 living in the Czech Republic, Finland, Flanders, France, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. For most children, these experiences are not frequent – they happen a few times per year. Daily attacks are reported by less than 1% of the children in all countries. There are no substantial age or gender differences in who is targeted by cyberhate, except in Poland where older children are slightly more likely to be cyberhate victims than younger ones.

Which children perpetrate cyberhate?

Sometimes children also send hateful and degrading messages or post comments attacking others. The number of children who are cyberhate perpetrators varies between 1% (Italy) and 8% (Poland, Romania). Again, the engagement in such activity was mostly occasional – less than 1% of children report that they have targeted someone weekly or more often.

Why should we be concerned?

Cyberhate can have negative impacts on the people who encounter it and on society as a whole. It is harmful to the victims who are targeted, for example, because of their belonging, family or origin, but it might have negative consequences also for people who come across it online. Catherine Blaya, Professor in Education Science at the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis and a co-author of the report, discusses the findings from France:

The emotional consequences are significant not only for victims but also for witnesses even though they are not targeted by the posted hateful contents. Both groups report experiencing anger and hate following their exposure or victimisation. It is important to take the issue seriously, even if percentages might seem low.

More hate in society leads to more intolerance – it normalises prejudices, discriminatory attitudes, and hateful behaviour towards already vulnerable groups and minorities. In extreme cases, it can lead to hate crimes and violence offline.

How to address the issue?

Cyberhate is becoming a fairly prevalent phenomenon and children experience it as part of their everyday online communication. Even though only a small number of children are cyberhate targets or perpetrators, the consequences might still be serious. Cyberhate attacks can be especially hurtful as they target identities and group belonging – characteristics which are often innate and unchangeable.

Hana Macháčková, Associate Professor at Masaryk University in Brno, the Czech Republic, who works on cyber aggression and took part in the writing of the EU Kids Online report, concludes:

We need to talk to children about their experiences of cyberhate and help them understand how to respond to such content. Direct involvement in both cyberhate victimisation and aggression is not very common but we still need to identify which children are more at risk and adjust prevention and intervention strategies accordingly.

Several international European campaigns cooperating with youth have been launched to combat cyberhate and protect children and adolescents from it. For example, the No Hate Speech Movement youth campaign offers several resources on how to fight hate speech by promoting tolerance and challenging hate narratives, including tools for educators, online activists, and cyberhate victims. Similarly, the SELMA (Social and Emotional Learning for Mutual Awareness) project Hacking Hate is focused on helping young people to better understand online hate and on providing them with strategies to combat it. The issue of cyberhate is also tackled by other initiatives focused on fostering a better and safer online environment for children and youth, such as Better Internet for Kids, or Safer Internet Day.

To effectively combat cyberhate, a joint effort of multiple stakeholders is needed, combining policymakers, internet companies and internet service providers, civic and youth advocates, educators, parents and children themselves. One way to reduce cyberhate is to report incidents or to block and remove hate sites and hateful content. However, the first and most important step lies in promoting tolerance and diversity and fostering an inclusive non-toxic online environment – this needs to be put into action not only at school and at home but also in the public domain.

The new report was launched recently as part of the EU Kids Online project, which maps the internet access, online practices, skills, online risks, and online opportunities of children in Europe. Teams of the EU Kids Online network collaborated between the autumn of 2017 and the summer of 2019 to conduct a major survey of 25,101 children in 19 European countries.

To read the full report: Machackova, H., Blaya, C., Bedrosova, M., Smahel, D., & Staksrud, E. (2020). Children’s experiences with cyberhate. EU Kids Online.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash