Digital technologies are often praised for having special relevance for children with disabilities, affording new opportunities and enabling their participation. These benefits, however, are not without limitations, as Alicia Blum-Ross and Sonia Livingstone discovered when interviewing children and parents for their new book, Parenting for a Digital Future: How hopes and fears about technology shape our children’s lives. In this blog we learn the story of 13-year-old Kyle who uses digital technologies to communicate, create and participate in his community of peers. Yet, far from being an equaliser for young people with disabilities like Kyle, digital technologies are accessed and experienced unequally, suggesting the need for more efforts to close the digital divide.

Digital technologies are often praised for having special relevance for children with disabilities, affording new opportunities and enabling their participation. These benefits, however, are not without limitations, as Alicia Blum-Ross and Sonia Livingstone discovered when interviewing children and parents for their new book, Parenting for a Digital Future: How hopes and fears about technology shape our children’s lives. In this blog we learn the story of 13-year-old Kyle who uses digital technologies to communicate, create and participate in his community of peers. Yet, far from being an equaliser for young people with disabilities like Kyle, digital technologies are accessed and experienced unequally, suggesting the need for more efforts to close the digital divide.

We met Kyle, 13, at London Youth Arts (LYA)—a cross-arts organisation running a digital media club (“LYA Interactive”) for children and young people with special educational needs (SEN). Lanky, with fiery red hair and pale skin, Kyle is passionate about art and design and has moderate to severe autism. In addition to observing Kyle in his class, we visited him at home, where he sat with us to show us his designs. Given that Kyle is mostly nonverbal, our understanding of the challenges and opportunities he faced in pursuing connected learning were supplemented by interviews with his parents (who are white, middle-income) and with the facilitators at his class, where he was part of a group developing a music player app.

From a young age Kyle has loved to draw, creating intricate logos and playing with words and fonts, which he has recently translated to computer art. Although he has no idea where Kyle found it, Kyle’s father Ryan recounted that Kyle had “downloaded, miraculously, professional architectural software.” When we visited, we saw that Kyle had downloaded the software SketchUp, a 3D-design program, and had begun to pursue a new interest—designing shopping malls. Ryan and Kyle’s mother, Amy, have tried to support this interest by taking Kyle on local outings, taking digital pictures to bring home, and helping Kyle with his designs. Ryan has taken printouts of some of Kyle’s designs to the teachers at his special school but has been frustrated by their lack of follow-through on incorporating Kyle’s digital interests into their planning for him.

Ryan described Kyle’s “understanding of computers [as] very innate” and so when another parent at Kyle’s specialist school for children with autism mentioned the evening class, Ryan and Amy jumped at the opportunity. Although he already has the “ability and the skills,” Ryan and Amy wanted to enrol Kyle in the digital apps club because of the “socialising aspect of it” as much as for the content, building on “something that he enjoys” to help him work on his ability to be with other young people. Ryan also wanted to

encourage him with his creative endeavours on digital media because … [of] the satisfaction that can come from creating things rather than just wandering the internet.

According to Gus and Mia, the lead facilitators from LYA, “communication” and “friendship” are the main rationales for the course. Some of the young people use assistive technology apps and Gus says that in his experience, “nonverbal young people … are the most adept users of technology I’ve encountered.” When asked what she hopes Kyle will gain from the class, Mia says,

It would be great to see if he could really build upon his communication and listening skills. … I would like him to be able to be part of the group … and be more engaged in it. … That would be a massive achievement for him.

Ryan shared the facilitators’ hopes about communication, worrying on Kyle’s behalf that “those who don’t speak … [people think] they don’t exist.”

The staff at LYA who run the SEN activities have more responsibility than others for liaising with the parents, and they do lengthy intake interviews and reach out to parents to let them know how the class is going. Mia, for example, knew about Kyle’s use of SketchUp and had considered running a session with it at LYA but worried that Kyle would just replicate what he had already been doing.

Instead, Mia and Gus designed a session using an app called PhonoPaper (which produces sound-enabled “tags” like audio QR codes), where they could explore the built environment around the school inspired by Kyle’s interest in shopping malls—although, ironically, Kyle was absent that day. When we asked Gus about whether LYA made an effort to link to what the young people did at home, he wondered whether the participants might want to keep what they did at LYA

entirely separate from all that [the other parts of their lives]. … I think they come to LYA and they associate it with certain things and experiences and feelings that they don’t have anywhere else.

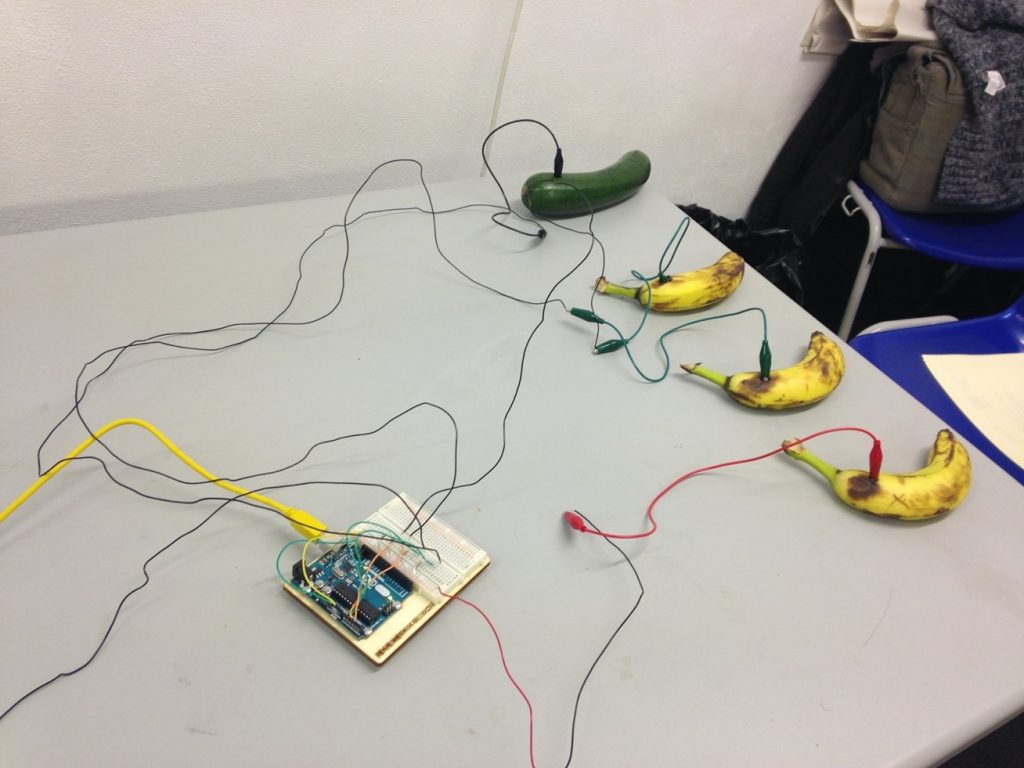

In a sense, then, he wondered if the experiences at LYA were too connected, they might lose their value. During the class the facilitators worked to connect technology with physical experiences. For example, they combined drama and drawing, and one week they brought in an Arduino to hook up to the music app the participants had been building (using software called Max, a visual programming language used by musicians). Connecting fruit and vegetables to the leads, the facilitators had the participants create a percussive song by completing the circuits and triggering the app they had created. Although it took him some time to settle into the activity, and the physical dexterity of connecting the wires was difficult, Kyle tapped the banana rhythmically when asked.

Looking into Kyle’s future is fraught. The support that LYA receives finishes when the participants hit 18—what Mia calls the “cliff edge.” Although his parents believe that Kyle has talent, when asked whether they thought graphic design might be something he could pursue after finishing his time at LYA, Ryan and Amy were not optimistic. Although Kyle might have the ability to work at the level required by art school, they thought it would be “totally inappropriate for him because he just loses interest.” So although they have hopes about how digital media helps him express himself, at the end of the day it is about his “motivation” and that digital and artistic skills are still “of no use if you can’t work with people,” and that to work as a designer “you’ve got to [be able to] listen to your client,” something they cannot envision Kyle as being able to do.

Kyle and his family, and educators, show both the possibilities and limitations of connected learning. When everyone is working together, Kyle’s interests at home translate into activities at his afterschool learning site, although there are missed connections that are both intentional—as disconnections are sometimes by design— and default. LYA is nimble enough to be able to respond, whereas often Kyle’s school is not, but even when the facilitators at LYA attempt to support him Kyle cannot always engage. The facilitators at LYA are well intentioned, but they do not have autism-specific training unlike the teachers at his school, so the activities they design sometimes miss the mark. Even with all these supports, Kyle’s version of connected learning will probably not translate into future employment or a traditional notion of academic success, but the hope is that it will help him communicate, create, and participate in his own way in his community of peers in the present.

Notes

This text was originally published by the Connected Learning Alliance as part of the report The Connected Learning Research Network: Reflections on a Decade of Engaged Scholarship. The text is reposted with permission and small edits.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Karolina Grabowska on Pexels