“Welcome to the World of Twisted ToysTM, a wonderland of excitement, experiences and exploitation. We pride ourselves on making toys that are addictive, risky and put you completely under our control”. The claim that welcomes users on the website is intentionally creepy: Twisted Toys is not the latest collection of digital gadgets for kids. Rather, it is a campaign launched by the 5Rights Foundation to expose the surveillance, exploitation and risks of the digital world for children. For www.parenting.digital, Giovanna Mascheroni and Andra Siibak discuss how poor design, aggressive marketing strategies, and greedy datafication compromise children’s online experiences, agency and rights.

“Welcome to the World of Twisted ToysTM, a wonderland of excitement, experiences and exploitation. We pride ourselves on making toys that are addictive, risky and put you completely under our control”. The claim that welcomes users on the website is intentionally creepy: Twisted Toys is not the latest collection of digital gadgets for kids. Rather, it is a campaign launched by the 5Rights Foundation to expose the surveillance, exploitation and risks of the digital world for children. For www.parenting.digital, Giovanna Mascheroni and Andra Siibak discuss how poor design, aggressive marketing strategies, and greedy datafication compromise children’s online experiences, agency and rights.

The series of mock hybrid playthings include:

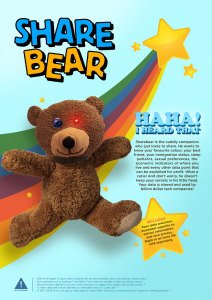

- a teddy bear that spies on children and shares their data with an undisclosed, ever-expanding list of third parties;

- a ‘stalkie talkie’ that matches children with adult strangers using sophisticated algorithms;

- a night light with addictive features, designed to keep children awake by claiming constant attention;

- a fishing game where children are asked to fish for likes on social media;

- a “pocket troll” that targets the child with any sort of hate speech; and many more.

Datafication and algorithms in children’s lives

Twisted toys raise awareness on the growing datafication of children’s lives: through their engagement with digital platforms, Internet-connected toys, and other IoTs (Internet of Things) such as smart speakers, children are exposed to million data trackers each year, and generate an unprecedented amount of data traces. Data about children are also left behind by their parents – for example, through the practice of sharenting, which, too, has witnessed a dramatic growth during times of social distancing.

Indeed, as we argue in our forthcoming book— Datafied Childhoods: Data practices and imaginaries in children’s lives (out in Autumn for Peter Lang)— the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the normalisation of datafication in children’s and families’ everyday lives: we have now come to rely on digital technologies for almost every aspect of children’s lives, including learning, keeping in touch with family and friends, and play. In this digital by default scenario, parents are also increasingly invited to use apps and software to monitor their children’s engagement with digital media, reduce screen time and protect them from online dangers. Yet, parental control apps have also been found unsafe: indeed, free parental control apps on the market generally track huge volumes of data that add up to the child’s and her/his parents’ digital dossiers. Moreover, they have been proven vulnerable to attacks and data breaches. Simply put, more data is not the solution to the already existing threats associated with children’s datafication.

The consequences of such coerced digital participation are both short- and long-term. How the provision of personalised content based on always more effective algorithmic classification will impact children’s identity, including their obsession with popularity metrics and quantification, and their socialisation to stereotyped identities? How will it shape how children access online services and information? And will it pre-determine children’s life trajectories, by regulating access to education, health, the labour market, credit, etc.? These are some of the concerns that guide the debate on the consequences of datafication for children’s future, that we discuss in the book.

The consequences of such coerced digital participation are both short- and long-term. How the provision of personalised content based on always more effective algorithmic classification will impact children’s identity, including their obsession with popularity metrics and quantification, and their socialisation to stereotyped identities? How will it shape how children access online services and information? And will it pre-determine children’s life trajectories, by regulating access to education, health, the labour market, credit, etc.? These are some of the concerns that guide the debate on the consequences of datafication for children’s future, that we discuss in the book.

Parents, educators, researchers and policy makers are increasingly worried. Yet, the risks of datafication are hidden beneath and behind reassuring products: think of the cute Amazon Echo Dots Kids Edition, about to launch in the UK, that comes with a cute tiger or panda design, parental control and other features to appease worried parents. Indeed, the child is immersed in the child-safe, age-appropriate world of Amazon Kids, and is invited to learn how to be polite with the positive reinforcement for ‘please’ feature (one of the main worries of American parents). Parents, on their side, can limit the time spent by their children with Alexa, or filter out inappropriate content such as lyrics in songs. Parents are also allowed to switch off the recording of conversations. However, is this really what age-appropriate design means?

Other risks

The Twisted Toys campaign addresses further risks that online platforms and digital gadgets pose to children and their parents, including: addiction, cyberbullying and hate speech, grooming and online abuse, frauds, identity theft. While these risks are not intentionally designed within platforms, apps and other products — indeed, these are often a side effect of children using services that have not been designed for them — yet, these risks further expose how the digital world is not child-friendly. Internet companies prioritise profit to the detriment of children’s best interests and rights, to the point that children are often dismissed as undesirable users.

Positive, safe, inclusive and creative digital play

Play is vital for children, as it supports their emotional, cognitive and physical wellbeing and development. Yet, as the Twisted Toys campaign exposes, poor design, aggressive marketing strategies, greedy datafication, and even automated data-driven personalisation of content compromise children’s experience of digital play, as they minimise children’s agency and impact the quality of free play. Ensuring opportunities for stimulating and beneficial free (digital) play require designing inclusive, accessible, safe, private, age-appropriate, adaptable digital playgrounds and products. In a word, it means implementing child’s rights online and putting children’s interests, not commercial interests alone, at the centre.