Young people’s online safety depends on dialogue with their carers, but children in foster care struggle to talk to their carers about sensitive topics such as nudes, body image, racism, bullying or harms they encounter online. For www.parenting.digital, Adrienne Katz discusses the role of digital technologies in the lives of children and young people living in foster homes and how restrictive parenting measures might harm rather than help online safety.

Young people’s online safety depends on dialogue with their carers, but children in foster care struggle to talk to their carers about sensitive topics such as nudes, body image, racism, bullying or harms they encounter online. For www.parenting.digital, Adrienne Katz discusses the role of digital technologies in the lives of children and young people living in foster homes and how restrictive parenting measures might harm rather than help online safety.

Offline vulnerabilities increase the likelihood of encountering particular online risks – we discovered this through the work of our research and practice partnership which has focused on vulnerable children and the role of the digital environment since 2017. In addition, relationships between online risks, that in turn increase the chance of harm, can be understood and anticipated so that proactive efforts can be made to support young people, and build their digital resilience.

Our series of studies and survey reports also show how vital digital connectivity is for vulnerable children with the benefits digital spaces afford: such as apps for sleep and mood, or accessibility tools. The online world is both a risk and a refuge, an essential connectivity tool for these children who are frequently socially isolated.

However, as we learned in a new programme creating a training course for foster carers, managing digital lives can be a challenge for young people in foster care – each home has different rules about digital life and arguments about online issues or wi-fi access can contribute to a breakdown in relationships with carers.

‘I would definitely find it difficult talking to a foster carer if I didn’t feel I could trust them, and that takes time.’

‘I’ve been so used to not talking to people about things anyway.’

‘It’s like they don’t even know me, so I’m going to tell them stuff like that, am I, and like they don’t get it. I know they’d over-react.’

The role of trust and communicating openly

When placements break down, a child can feel like a commodity. In the words of one male participant – it can feel like being ‘Moved around like an Amazon package’. Teens are more likely to experience multiple placements than younger children. Their online lives are also more complex. Communication and problem-solving together with the carer are much more efficient than an overly restrictive approach which can heighten the risk of harm.

When placements break down, a child can feel like a commodity. In the words of one male participant – it can feel like being ‘Moved around like an Amazon package’. Teens are more likely to experience multiple placements than younger children. Their online lives are also more complex. Communication and problem-solving together with the carer are much more efficient than an overly restrictive approach which can heighten the risk of harm.

Young people tend to seek workarounds when denied online access at home. They hack controls or privacy settings, use hidden apps or accept ‘gifts’ of phones. They hang out where there is free wi-fi in public spaces.

We conducted workshops with 40 children and young people in July-August 2021 to explore their needs, ideas and lived experience of online life in foster care. The workshops were run by Enable (a consortium of partners led by Kingston University and managed by Youthworks) to explore what is needed in a training course for foster carers. The 40 young participants were from 6 local authorities and more than half had experienced at least 3 foster home placements so far.

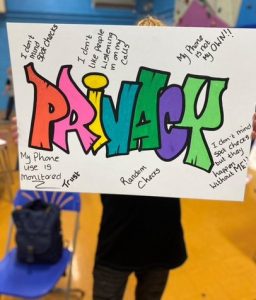

These teenagers repeatedly raised the important role of trust between carer and child over online issues. They described what helped to build or destroy it and how long it took for them to trust a foster carer. Tales of carers or social workers seemingly ‘overreacting’ or ‘combusting’ in response to online incidents also reverberated through the workshops in urban art, discussions and question booklets.

Arbitrary instructions can damage relationship building

Not unexpectedly, the 70 foster carers outlined different needs in a survey. They described the enormous responsibility they shoulder as they try to keep children safe online, and the implications, personal, professional and agency-wide, if they fail. Foster carers rated their prior training poorly[i] and described varying levels of support available to them. As a result, they opted for approaches that were risk averse and relied on punishments, such as confiscating phones or denying wi-fi access.

Advice given by social workers or agencies was sometimes hard to implement or risked damaging the relationship carers were trying to build with a child. For example, carers were sometimes advised to tell a child to uninstall an app on which they depend to connect with their friends or siblings. This, children revealed, can encourage deception or defiance – often leading them to uninstall and later reinstall this app. Foster carers were frequently instructed to monitor a teen’s phone, but not taught what to look for when they do. This can be a minefield. Most teens viewed this monitoring as a major intrusion into privacy. Yet, for one girl, it was the ’the first time anyone cared if I was safe’.

While building trust and maintaining a good dialogue about online life are vital to make a young person safer online, this takes time to develop. It may be undone by arbitrary rules made without negotiation or explanation, such as the ‘My house, my rules’ approach, which foster carers were often told to impose when the child first arrives.

‘It’s about trust…I need to be able to trust them but that takes time and if they’re putting loads (of) rules in before I even know them, it’s like you don’t trust from the start’.

One experienced foster carer said in an interview that she would do it differently now if she fostered a child again, attending to the child’s emotional needs on the first night and Wi-fi access and phone rules later.

Training developed with user input

Our earlier research programme had identified gaps in practice and procedure in children’s services, as well as in assessment tools and training. With the support of Nominet, we developed the Enable-Pathway training: ‘Fostering in a Digital Age’ – a course that explicitly acknowledges and addresses the needs of vulnerable children and the different positions held by children and carers.

Our earlier research programme had identified gaps in practice and procedure in children’s services, as well as in assessment tools and training. With the support of Nominet, we developed the Enable-Pathway training: ‘Fostering in a Digital Age’ – a course that explicitly acknowledges and addresses the needs of vulnerable children and the different positions held by children and carers.

The training offers a new approach to fostering in a digital age, developed with young people in care, foster carers, online safety specialists and psychologists. It explores motivation, emotional need and theories that might explain our behaviour behind screens. Communication is emphasised and adults are not required to be all knowing but to go on this journey with their young people, listening, exploring, leading – and sometimes following. Foster families are encouraged to create an environment where a child is able to tell their carer that something has gone wrong without fearing an angry judgemental reaction.

Bringing psychologists on board injected another point of view, emphasising the child’s wellbeing, exploring motivation and theories that might explain behaviour. An extensive library of supporting resources and tools is provided for trainees. The supporting resources might help foster carers handle difficult situations.

Evaluation is underway. Changes in the trainees’ confidence, approach and understanding will be measured in two waves by Kingston University. The first, at enrolment and a second at the end of the accredited course. The trainees will also deliver their verdicts on each module of the course as they work through it.

Further resources

Enable-pathway training and the resource and tools library are free to UK foster carers.

Trust Don’t Combust – Report of the youth engagement workshops

Video: Themes from the youth engagement workshops

Fostering in a Digital Age report – Foster carers’ views

enable is a consortium led by Dr Aiman El Asam, Associate Professor of Forensic Psychology at Kingston University, London. The project is managed by Adrienne Katz who is content editor. Youth engagement is by John Khan and Tom Goulden of Priority 1-54.

enable is a consortium led by Dr Aiman El Asam, Associate Professor of Forensic Psychology at Kingston University, London. The project is managed by Adrienne Katz who is content editor. Youth engagement is by John Khan and Tom Goulden of Priority 1-54.

Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council and the National Association of Fostering Providers are partners in this consortium. This programme is supported by Nominet.

First published at www.parenting.digital, this post represents the views of the authors and not the position of the Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

You are free to republish the text of this article under Creative Commons licence crediting www.parenting.digital and the author of the piece. Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence.

Image cerdits: Photos by Enable

[i] 2/3 of our 70 foster carers said their training had not included online safety tailored for vulnerable children, only 37% said any online safety was included in their foster carer training, while 24% said it was included in Safeguarding training.