Ever since Theresa May triggered Article 50, 29 March keeps being portrayed as Brexit day. This continues to be the case, even though it is highly likely that an extension will be requested. Jonathan White explains why the focus on this deadline has a number of aims, not least to weaken resistance.

Ever since Theresa May triggered Article 50, 29 March keeps being portrayed as Brexit day. This continues to be the case, even though it is highly likely that an extension will be requested. Jonathan White explains why the focus on this deadline has a number of aims, not least to weaken resistance.

29 March 2019 has dominated British politics for some time. The date continues to do so, even as it becomes clear that Britain’s EU relationship may not be settled by then. Whether or not a version of the Withdrawal Agreement passes, further time seems likely to be sought, possibly to hold a referendum. Given the likelihood of some kind of overrun, why does 29 March still loom large?

Clearly one reason is that the Government has reason to emphasise it. Deadlines are useful for a certain kind of emergency politics. A date is a way to focus minds. We have recently seen the Prime Minister postpone a ‘meaningful vote’ once more, shrinking further the time available for a decision and keeping No Deal in sight. A ticking clock ticks loudest when there’s a deadline.

Courting No Deal has something of the self-cancelling prophecy about it. Such prophecies are intended to prevent the future they foretell, allowing their authors to pursue outcomes they prefer. The Prime Minister’s circle seems conscious of this. Ministers raise the prospect of disorder – the chaos of no-deal, of martial law – precisely as a way to pursue order, i.e. to promote the Agreement. As many suspect, and as Labour has highlighted, the Tory leadership seems intent on steering events towards a binary choice between No Deal and ‘May’s Deal’ – a dichotomy to exclude alternatives and encourage all but the most reckless to fall in line. This has a chance of working only if there is a deadline to point to, something to give urgency to the choice.

Beyond Westminster of course it can look more like a self-fulfilling prophecy. The same strategy provokes further anxiety within markets, companies, citizens and EU authorities. There is a cycle at work, whereby the rhetorical efforts of a government to raise the stakes raise them materially. Postponing votes in Parliament gives more time to convey the risks of No Deal, but also increases the credibility of those risks by reducing the political scope for manoeuvre. The executive puts itself in a position where it can plausibly claim the demands of necessity. In the heresthetics of emergency, governing officials aim to capitalise on uncertainties and constraints that they themselves have co-produced.

Emergency politics underpinned by deadlines is by no means unique to Brexit. At the height of the Euro crisis, Chancellor Angela Merkel was one figure suspected of dragging her feet in EU negotiations so as better to fend off opposition from the Bundestag, German Court and wider public. Having established a doctrine of ‘ultima ratio’, by which certain decisions would be taken only as acts of last resort, she went about establishing the conditions that might warrant this by delaying key eurozone moves until the stakes were sufficiently high. Market deadlines loomed. The effect was to construct more clearly a dichotomy of order and imminent disorder, giving dissenters strong reason to accept the government’s position.

One tends to think of emergency decisions as all about speed, but sometimes it’s about going slow. Speed can be selectively deployed, so that at critical moments the need for it can be impressed on others. Deadlines can be turned to advantage. And raising the stakes need not be unilateral. The European Commission has also publicised its emergency plans for the day after 29 March, presumably aware that doing so may heighten the prospects of a deal.

Naturally such tactics are often about weakening resistance. Emergency politics in the shadow of a decisive moment is a way to give people reason to accept decisions they oppose. Whether they see through such moves and denounce them as ‘Project Fear’ is only relevant up to a point – the dangers, after all, are often real enough. Perhaps such moves are also a way to weaken parliamentary resistance, though arguably some parliamentarians may welcome them. For the more yielding, emergency politics offers a rationale for avoiding tough decisions. By highlighting such pressures as reasons for action – pressures readily confirmed by other authorities of the public sphere – MPs can tell disgruntled constituents and party members they had little choice. They too have reason to embrace the deadline.

There is also a larger story to tell. Deadlines and pivotal dates seem increasingly central in contemporary societies across a range of contexts. Financial capitalism is all about setting time-limits for when debts are to be repaid or renegotiated. As the Euro crisis suggested, states increasingly live by the temporality of markets. In the EU, deadlines have also long been used as political coordinating devices – as ways to clinch agreement between the many. The fateful moment is a way to get things done.

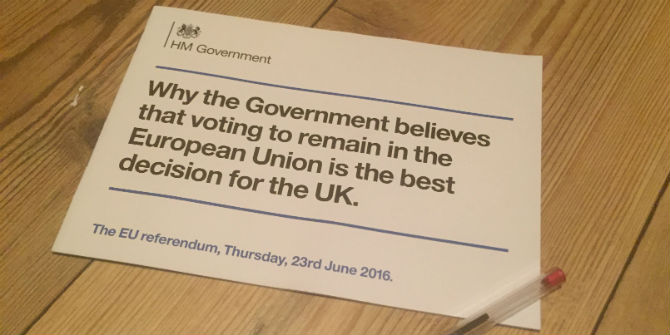

There are problems that come with a world of deadlines, not least how it provides fodder for the politics of emergency. The 2016 Brexit vote was ironically in some ways a repudiation of this. Of the many sentiments behind the vote to Leave, one was surely a rejection of the politics of threats. The Leave Campaign defined itself by hostility to the ideas of economic emergency put forward by forecasters in the Treasury, IMF, EU institutions and the markets. It was an effort to reassert the primacy of politics over economics, identifying this as a project for the sovereign nation-state.

Less clear is whether such sentiments can survive the process of leaving itself. Advocates of a No-Deal Brexit aside, the whole of British politics now seems to be relying on the prospect of emergency to avoid one. Brexit is further undermining some of the very qualities that were sought in an exit.

Deadlines get us thinking about the immediate future, but they can make it harder to think about the longer term. Attention is focused on a particular moment: we become trained in thinking about 29 March, but less good at conceiving the follow-up. A deadline carves out a period of time as an episode unto itself. However longstanding the socio-economic and power issues in play, they become harder to connect to the before and after. A focus on dates can eclipse the awareness of a process.

Perhaps the most general reason we pinpoint such dates is in the hope they mark the end to something. 29 March promises a conclusion, a clean break with the past. Such dates in politics do not exist.

_________________

Jonathan White (@jonathanpjwhite) is Professor of Politics at the LSE’s European Institute. He is completing a book on emergency politics in contemporary Europe, entitled Politics of Last Resort.

Jonathan White (@jonathanpjwhite) is Professor of Politics at the LSE’s European Institute. He is completing a book on emergency politics in contemporary Europe, entitled Politics of Last Resort.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

Can the Government be certain that one or more of the EU member states will not be prepared to allow the can to be kicked any more, and reject our request for an Art 50 extension. They would have reasonable grounds because it is certainly not clear that the extension will be productive in any way. Does parliament have a plan to cope with this situation?